From the SWISS BULLETIN: The Two Mules

Here’s a humorous mule tale for all of you Longears Lovers to read from our friends in Switzerland. ENJOY!

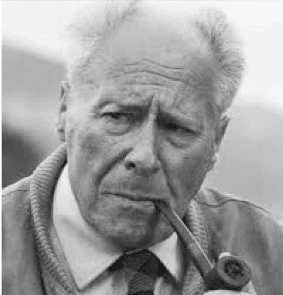

Maurice Zermatten

Pierre Bovier tied the rope around the iron bar that follows the wall; with the back of his hand he hit his mule on the back, as a sign of his friendship. He pulled a crackling piece of hay out of the oat sack, took his two cheeses under his arms and walked away. It was still winter up there, no relief was to be seen anywhere; dirty snow, half melted from the wind, covered the whole slope with a lifeless blanket. Perhaps the young grain’s stalks were already trembling beneath him. The grass sounded like the call of spring. The roots trembled in the frosty earth. Impatience ate the souls of the people. But the plain shone in the bright spring light. Pierre Bovier saw spring from his village Euseigne. Every day he watched for a long time the triangle of sap-laden earth between the sloping columns of the valley entrance. He would have loved to dig his working hands into the humid cold of the revived vines. He stretched his head, he looked and looked. Then he couldn’t stand it any longer. He could no longer stay in this house surrounded by death. He took his mule and he went away. So he went down to the valley and pulled his animal by the reins. The mule stretched his neck towards spring. Two small cheeses hung in the oat sack. He

Pierre Bovier tied the rope around the iron bar that follows the wall; with the back of his hand he hit his mule on the back, as a sign of his friendship. He pulled a crackling piece of hay out of the oat sack, took his two cheeses under his arms and walked away. It was still winter up there, no relief was to be seen anywhere; dirty snow, half melted from the wind, covered the whole slope with a lifeless blanket. Perhaps the young grain’s stalks were already trembling beneath him. The grass sounded like the call of spring. The roots trembled in the frosty earth. Impatience ate the souls of the people. But the plain shone in the bright spring light. Pierre Bovier saw spring from his village Euseigne. Every day he watched for a long time the triangle of sap-laden earth between the sloping columns of the valley entrance. He would have loved to dig his working hands into the humid cold of the revived vines. He stretched his head, he looked and looked. Then he couldn’t stand it any longer. He could no longer stay in this house surrounded by death. He took his mule and he went away. So he went down to the valley and pulled his animal by the reins. The mule stretched his neck towards spring. Two small cheeses hung in the oat sack. He  would sell this cheese, he would pay his debts to the bank. Two twenty-franc notes, a few glasses of wine to drink with one he meets in the bustling city before climbing back up to his village. This is our life. The reins are stretched, the mule hurries forward. Now Pierre Bovier is looking for a place in the city to put up his cheese. It is wonderfully warm. The sun makes its bright spots dance on the roadsides, the light stops on the groups of women, hangs on the yellow wicker baskets dangling from its arms. In the fishmonger’s display the sun delicately silvered the scales, sticking tinsel gold into the fur of the thick rabbits that are destined for the cooker. “What is the cheese?” “Twenty-five francs a piece.” The deal was closed, and Pierre Bovier walked straight to the bank, pulled out of his pocket a green, dirty envelope; paid. When he was back on the street he suddenly felt a strong thirst at the bottom of his throat and he decided, to satisfy it immediately.

would sell this cheese, he would pay his debts to the bank. Two twenty-franc notes, a few glasses of wine to drink with one he meets in the bustling city before climbing back up to his village. This is our life. The reins are stretched, the mule hurries forward. Now Pierre Bovier is looking for a place in the city to put up his cheese. It is wonderfully warm. The sun makes its bright spots dance on the roadsides, the light stops on the groups of women, hangs on the yellow wicker baskets dangling from its arms. In the fishmonger’s display the sun delicately silvered the scales, sticking tinsel gold into the fur of the thick rabbits that are destined for the cooker. “What is the cheese?” “Twenty-five francs a piece.” The deal was closed, and Pierre Bovier walked straight to the bank, pulled out of his pocket a green, dirty envelope; paid. When he was back on the street he suddenly felt a strong thirst at the bottom of his throat and he decided, to satisfy it immediately.

Drinking doesn’t always quench thirst. Pierre Bovier ordered three pints, then, still thirsty, another three. He liked it quite well in this pub full of clouds of smoke. He met a few friends here every time and the landlady could testify that they did not part before drinking friendship several times. But just today he didn’t know anybody. Maybe someone would come soon. There must have been a farmer at the next table, as lonely as he was. He did not look very social. At least you could try it. The misfortune wanted them to turn their backs. You had to wait for something, for something in common, to get close to each other. Outside the early February spring was still blowing through the streets. It was so beautiful, so light, so full of smiles, that it made you feel like brothers. One suffered from his loneliness. There he could not stand it any more. “What weather!” The other turned around and said, “Yes, one has never seen anything like it before.” That was enough. They closed their loneliness together, ordered half a liter. “Health!” “Health!” They soon realized that they were made to understand each other, because they had the same thirst and the same worries. Soon there was a certain familiarity between them. They talked about cattle prices, politics, and wine. They understood each other in all points: The cattle sold badly. The government ruled even worse. As far as wine was concerned, it was a shame. “Health!” “Health!” “With us in Ayent…” Ayent, but that was the village Pierre Bovier saw over the plain, just across from him on the other side of the river Rhone. Often he had wanted for his own village to have this spot in the sun, this early spring, while in his case. But he did not want to grieve. The afternoon passed in an instant, and the evening light was already sinking against the windows. The nights come early, in February. You hardly have time to sit down quickly and toast. The landlady turned the switch on. Again it was bright in the pub. The two friends were happy about it and ordered another half. “The conservatives …” said one. “The radicals …”, said the other. They mistook everything, by the way, put on the account of the radicals the political mistakes of the conservatives and accused the conservative leaders of clumsy words spoken by a leader of the radical party. What else did that do? They also mistook their glasses and would drink from one, then from the other glass.

It struck eleven o’clock. The landlady refused them the last half liter. So they had no choice but to leave. They rose and were outraged at this heartless creature, that had placed them in front of the door, stumbled between the tables, swayed down the street in all its width, finally trusted the walls, and when the walls stopped, they supported each other’s disturbed balance. They would have liked to drink another glass, equalize the other glasses. But all the doors were closed. So they had to do without, for better or for worse, and they did it by scolding the bad times. They decided to return home, the one from Ayent to Ayent and Pierre Bovier to Euseigne. “Where do you have your mule?” “There he is, next to yours.” The mules waited in the cool night. Swaying, the fathers (lads) gave each other their hands and then loosened their animals. It was no small thing for them to get on the saddle. After all, Ayent’s succeeded first, after some unsuccessful attempts. And the mule rode off with the hasty step of a hungry animal. Euseigne, for his part, managed to climb the animal after many attempts and violations of the second commandment. A lucky fool shortened the way home. Almost at the same time, the two companions felt their animals stop. We have arrived, said the mule’s frozen gestures. “Where am I,” stammered the one from Ayent, for he no longer knew his barn. “But I am in Ayent,” the one from Euseigne suddenly sobered. After they had confused the radical doctrine with the conservative, then their glasses, they had now also confused their mules. But the mules had not been wrong in their way home.

It struck eleven o’clock. The landlady refused them the last half liter. So they had no choice but to leave. They rose and were outraged at this heartless creature, that had placed them in front of the door, stumbled between the tables, swayed down the street in all its width, finally trusted the walls, and when the walls stopped, they supported each other’s disturbed balance. They would have liked to drink another glass, equalize the other glasses. But all the doors were closed. So they had to do without, for better or for worse, and they did it by scolding the bad times. They decided to return home, the one from Ayent to Ayent and Pierre Bovier to Euseigne. “Where do you have your mule?” “There he is, next to yours.” The mules waited in the cool night. Swaying, the fathers (lads) gave each other their hands and then loosened their animals. It was no small thing for them to get on the saddle. After all, Ayent’s succeeded first, after some unsuccessful attempts. And the mule rode off with the hasty step of a hungry animal. Euseigne, for his part, managed to climb the animal after many attempts and violations of the second commandment. A lucky fool shortened the way home. Almost at the same time, the two companions felt their animals stop. We have arrived, said the mule’s frozen gestures. “Where am I,” stammered the one from Ayent, for he no longer knew his barn. “But I am in Ayent,” the one from Euseigne suddenly sobered. After they had confused the radical doctrine with the conservative, then their glasses, they had now also confused their mules. But the mules had not been wrong in their way home.

—-

From the magazine: Zürcher Illustrierte

Volume (year): 14 (1938), Issue 11