By Meredith Hodges

By Meredith Hodges

My equines taught me that in order to make an educated decision about which tack and equipment to use, one needs to take into account the anatomy of the equine and the effect it will have on his body movement during different activities. Good conformation is important in allowing the equine to perform to the best of his ability, but so is developing core strength elements (muscles, ligaments, tendons, soft tissue and cartilage) such that the skeleton is ideally symmetrically supported. The equine’s body can then move freely and using his joints properly in good equine posture. This will add longevity to his use life and will minimize arthritis and other problems during his life. Lower vet bills are always a bonus!

Feeding: When developing the equine’s body, it is important to know what feeds are the healthiest for him. There are lots of different ways to feed your equines today, but I have found a regimen that works best. I did this through constant and continual research using a field study for more than 50 years with 32 equines of varying breeds, types and sizes.

Feeding: When developing the equine’s body, it is important to know what feeds are the healthiest for him. There are lots of different ways to feed your equines today, but I have found a regimen that works best. I did this through constant and continual research using a field study for more than 50 years with 32 equines of varying breeds, types and sizes.

- Most feeds are tested in laboratories.

- Dehydrated feeds take fluids from the digestive tract and can cause choking (researched with my vet). You cannot add enough water to replace the fluids that are naturally in the digestive tract.

- The oats, Sho Glo, Mazola corn oil and grass hay produce ideal body shape and conditioning, even with minimal exercise.

- Sho Glo gives the body the nutrients it needs for daily maintenance.

- Supplements should not be fed without first getting a base line of what the animal is lacking.

- Salt and other minerals should be free fed in a trace mineral salt block. White salt alone, or minerals measured and put in the feed, can often be the wrong amounts.

- The equine will use the trace mineral salt block when and how often they need to. It is their “Natural instinct.”

- Mazola corn oil (no other) keeps the hair coat healthy, the feet ideally lubricated and hard, and maintains the ideal conditioning of the digestive tract regularity.

- We feed a Brome/Orchard Grass mix that we harvest ourselves. We feed the hay three times a day and the oats mix once a day in the evenings. Never feed broad leaf hay like Alfalfa, Clover or Fescue Grass Hay.

- Fescue Grass Hay has been proven to cause spontaneous abortions. Since it has this toxic effect, it would probably not be good for any equine, pregnant or not.

- Our equines are kept in dry lots, or stalls and runs. We limit their turnout to five hours a day to prevent obesity and other problems like allergies, prolonged exposure to flies and other insects that live in the grassy pastures.

- Use no types of rewards or “treats” besides crimped oats (or any other kind that is broken open). They cannot digest whole oats, and other “treats” can cause gas or other irregularities in the digestive tract that can lead to colic, twists, founder and even allergies.

- Our equines are wormed with Ivermectin every other month with the cycle broken in November with Strongid. This regimen prevents the cycle of worms (No fecal tests are needed because the larvae never have a chance to mature and show up in the manure).

- This regular and frequent use of Ivermectin helps to repel flies along with a weekly spray of Farnam Tri-Tech 14 (sometimes twice a week if the flies are inordinately thick). Ivermectin is a totally safe drug and their bodies do not build up a resistance to it.

Most equines on other kinds of feeding programs develop bodies with a protruding spine and a “hay belly” hanging from it. The shape is quite different from a balanced body with core strength. They have an indentation along both sides of the spine instead of having a spine that “melds” into the torso with uniform conformity. My feeding program produces an ideal body shape with ALL my equines with minimal exercise. The SHAPE of the animal’s body is important for the correct fit of the tack and equipment.

Most equines on other kinds of feeding programs develop bodies with a protruding spine and a “hay belly” hanging from it. The shape is quite different from a balanced body with core strength. They have an indentation along both sides of the spine instead of having a spine that “melds” into the torso with uniform conformity. My feeding program produces an ideal body shape with ALL my equines with minimal exercise. The SHAPE of the animal’s body is important for the correct fit of the tack and equipment.

Tack and equipment should fit YOU and YOUR EQUINE like a glove. This will minimize resistive movement that can interfere with your equine’s posture and ability to travel smoothly. When tack and equipment is stabilized, it is easier for you to stabilize your balance seat and improve your riding ability. There are so many saddles and tack to choose from these days that it can be quite daunting. Choices can be difficult for both riding and driving.

The tack and equipment we use has an effect on the equine’s movement in spite of his shape. In order to obtain freedom of movement, the elements of the equine’s anatomy must be considered so he is allowed to move freely through every joint of his body.

Mule Bars are not necessary if you have a well-made saddle and have a professional saddle maker shave the saddle tree flat at the gullet. My 1972 Circle Y Stock, Equitation and Longhorn saddles have worked on all my mules for more than fifty years with that minor adjustment.

If you want to be able to balance your own body in the saddle, it not only needs to fit your equine, but it needs to fit YOUR body as well. The saddle needs to sit LEVEL across his back so you can sit up straight in a balanced position with the only deep contour directly below your seat bones. The rest of your body should be able to move freely through your hip joints You should be able to comfortably sit up straight with your legs resting relaxed below your core that is located behind your belly button. Your relaxed legs should gently “hug” your equine on both sides with your whole body perpendicular to the ground when halted. This way, cues from your legs will not be abrupt and come out of nowhere to startle the equine. Saddles that restrict your position are not really a help to balance your seat and make cues effective.

The stirrups need to hang straight down over the center of balance on the equine, in the MIDDLE of his torso. Stirrups with Tapaderos can be safer that those without, but if the toes on your boots are too pointed and too long, they can actually hinder you from keeping your feet securely in the stirrups. You should never wear tennis shoes, or shoes with no heels, when riding. Ideally, your weight should be on the ball of your foot with the heel of your boot touching the back of the stirrup to keep your feet from sliding through the stirrups.

The stirrups need to hang straight down over the center of balance on the equine, in the MIDDLE of his torso. Stirrups with Tapaderos can be safer that those without, but if the toes on your boots are too pointed and too long, they can actually hinder you from keeping your feet securely in the stirrups. You should never wear tennis shoes, or shoes with no heels, when riding. Ideally, your weight should be on the ball of your foot with the heel of your boot touching the back of the stirrup to keep your feet from sliding through the stirrups.

The saddle should not simply be PERCHED on top. When you get on, you should be able to easily find the place for your seat bones over the center of gravity. Most saddles appear to be too high in the gullet with too many contours, and with insufficient body condition, it puts localized pressure that can cause chafing on both sides of the animal instead of spreading the pressure points over a wider area underneath the saddle. The saddle should fit such that it is stabilized on the equine when all girths and straps are secured. It will move WITH the animal without excess movement.

Localized pressure is particularly prevalent with sawbuck pack saddles. That is why you see so many pack mules with white spots at the withers…unbalanced loads that will shift. When the horn sits lower and the saddle pressure is spread across a wider area, the pressure is more comfortable for the animal and will not cause chafing. The saddle horn is another consideration. They are built in so many different ways, but a lot of those ways are cosmetic and often dangerous. Vaqueros that worked regularly with cattle and horses built their saddles with a thick and functional horn. The horns on a lot of saddles are built for function, but there are many that are simply cosmetically built. They are often too high and too narrow…a hazard if you happen to get thrown onto them.

Localized pressure is particularly prevalent with sawbuck pack saddles. That is why you see so many pack mules with white spots at the withers…unbalanced loads that will shift. When the horn sits lower and the saddle pressure is spread across a wider area, the pressure is more comfortable for the animal and will not cause chafing. The saddle horn is another consideration. They are built in so many different ways, but a lot of those ways are cosmetic and often dangerous. Vaqueros that worked regularly with cattle and horses built their saddles with a thick and functional horn. The horns on a lot of saddles are built for function, but there are many that are simply cosmetically built. They are often too high and too narrow…a hazard if you happen to get thrown onto them.

When a saddle does not allow you to ride a balanced seat, it creates unnecessary restive movement that can aggravate the equine and cause them to buck, run off, fall, or worse. Moving WITH the equine’s movement is essential. When your movement is blocked with things like dysfunctional swells in the saddle’s construction, or protrusions that are designed to keep your legs from sliding forward, it prevents you from keeping your balanced seat while following the equine’s motion. I have seen lots of people that get slung over the saddle horn and onto the neck when the equine resists. A girl friend of mine landed right on the saddle horn during an altercation like this with her equine and it still causes her pain, even today, after surgery to fix the injured area. Jumping in a Western saddle with a horn is dangerous and not recommended.

Trees of the past were often fashioned after that of a McClellan saddle that naturally molds itself to the equine structure. They have an open gap across the spine and are not padded in-full the way our modern saddles are…and they can be pretty hard on your rear when you ride from your seat bones. It occurs to me that these saddles were preferred by men because they also left more room for the genitals, although I have never seen this mentioned! However, I have heard cowboys complain about riding a balanced seat because they say it hurts THERE when they do!

I like to use cotton, or Mohair, string girths in front because they will stretch slightly, allow air flow and easy breathing. Beware of nylon string girths that can cause chafing because they do not stretch as well. I like leather girths for the back girth. When leather is properly cured and kept conditioned, it pretty much holds it shape, but will stretch a bit with the warmth from the equine’s body. This is why girths should be tightened a little at a time with a final check after riding for about 10-15 minutes. It is the same for the whole saddle. Saddles that are not made from leather do not mold and stretch with the equine’s body, and will wear out quicker that leather that is well managed.

The front girth should be snug, but not too tight. The back girth should be snug, but not as tight as the front girth. The two girths should be held together underneath with a leather strap that keeps them each in their respective place perpendicular to the ground. The back girth should be perpendicular to the ground and not on an angle to the rear in front of the flanks. They were developed only to hold down the back of the saddle (invented by ropers to balance the saddle when the steer is stopped).

Using the back girth to hold the saddle back might seem like a good idea, but it puts the pressure on the fragile undercarriage rib bones that can fracture easily. The under-carriage rib bones beneath a properly placed back girth are thicker and less likely to fracture under abrupt pressure. It can also cause too much pressure on the female genitals and small intestines, restricting optimal organ function. The rear girth should always be attached to the front girth underneath, hang perpendicular to the ground and should only be snug enough to keep the back of the saddle down.

Using the back girth to hold the saddle back might seem like a good idea, but it puts the pressure on the fragile undercarriage rib bones that can fracture easily. The under-carriage rib bones beneath a properly placed back girth are thicker and less likely to fracture under abrupt pressure. It can also cause too much pressure on the female genitals and small intestines, restricting optimal organ function. The rear girth should always be attached to the front girth underneath, hang perpendicular to the ground and should only be snug enough to keep the back of the saddle down.

ANY strap or girth that is too tight will irritate the equine and cause bad behaviors, chafing and saddle shifting. Any strap, or girth that is too loose, will not do its job, interfere with the equine’s ability to balance his body and will cause chafing.

As you learn to ride correctly and in balance, you also learn how to ride supportively by balancing on your seat bones with weight from your core (behind your belly button) going down through your legs and up through your torso. You can take the stress out of going uphill and downhill by staying relaxed in the saddle, rocking your weight through your core over your seat bones and by keeping your body in good posture.

Do not jam your heels down. Rather, think of keeping your toes up to stay relaxed. Lean the upper body back when going down hill, and forward when going up hill. Keep your upper and lower body in a straight line that operates from YOUR CORE, located behind your belly button. Think of the relaxed position of the Man from Snowy River as he was going over the cliff. Think of how Bronc Riders and Bull Riders balance just to stay on for eight seconds! Your SEAT is the fulcrum of a balanced, teeter-totter motion that will AID your equine in his movement and allow you to stay on board easily.

The shoulders on the equine are only attached with cartilage and need to be able to “float” freely forward with the legs through the front quarters when in motion. This means that the saddle should fit your equine like a glove and rigged so it cannot slide forward over the Shoulder Blades. When you sit on a horse bareback, your legs will find the “groove” right behind the shoulder blade.

The shoulders on the equine are only attached with cartilage and need to be able to “float” freely forward with the legs through the front quarters when in motion. This means that the saddle should fit your equine like a glove and rigged so it cannot slide forward over the Shoulder Blades. When you sit on a horse bareback, your legs will find the “groove” right behind the shoulder blade.

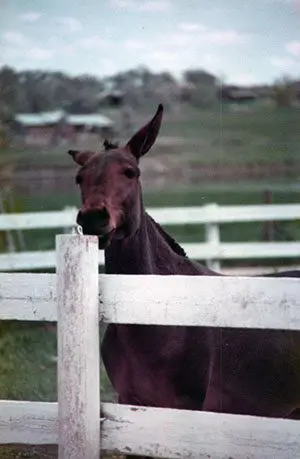

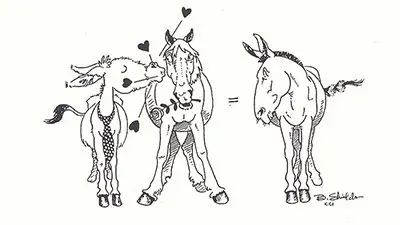

Breast collars are generally used with horses to keep the saddle from sliding backward. Breast collars are not advised to use with mules and donkeys. They are anatomically different from horses.  They do not have as prominent withers and there is a muscle that is located right where your legs fall into the “groove” on a horse. Their torso is comprised of smooth muscle and is straighter across and more compact than that of the horse that possesses more bulk muscle. The natural tendency on a mule or donkey is for the saddle to slide FORWARD, into the shoulder blades. It is advisable to use cruppers or breeching to help the saddle stay stabilized.

They do not have as prominent withers and there is a muscle that is located right where your legs fall into the “groove” on a horse. Their torso is comprised of smooth muscle and is straighter across and more compact than that of the horse that possesses more bulk muscle. The natural tendency on a mule or donkey is for the saddle to slide FORWARD, into the shoulder blades. It is advisable to use cruppers or breeching to help the saddle stay stabilized.

When in harness, the collar and traces should be fitted along the same angle as the shoulder blades and the point of draught should be at the base of the neck. The collar should be two inches larger around the neck to allow for free movement. A breast collar and traces should ride from the base of the neck. The breeching should be tight enough to enclose the equine comfortably in the harness assembly so they can easily go forward, or back up, with the immediate response of the vehicle. The tugs will carry the weight of the shafts and will aid in the movement.

People talk about allowing airflow to keep the spine depressurized and cool underneath the saddle. They use thicker therapeutic pads, or pads that are pre-shaped, stiff and sit stiffly on the equine’s back. I prefer to use Navajo blankets, and with older animals, or animals with higher withers, I will add a fleece pad underneath it. This allows for more flexibility, compression and molding of the saddle and blankets across the animal’s back…like a glove. To allow for more airflow, you just stick your arm under the blanket and across the spine before you tighten the girth. The blankets will move upward into the gullet and provide protection of the spine from any undue pressure. If the animal is in good equine posture with core strength in a solid balance, the saddle and equine will move as one with minimal abrasive movement. These can easily be kept clean by washing them in a washing machine and hang drying.

An animal with insufficient conditioning and balance will hollow his back and neck and try to compensate for his inefficiencies in muscle conditioning and movement. When the equine’s tack and equipment fit properly, the extremities have full range of motion so he can pick each step with confidence and no obstructions. When the skeletal system is adequately supported with symmetrical muscle strength and especially over the top line, the animal is better equipped to use his body efficiently.

An animal with insufficient conditioning and balance will hollow his back and neck and try to compensate for his inefficiencies in muscle conditioning and movement. When the equine’s tack and equipment fit properly, the extremities have full range of motion so he can pick each step with confidence and no obstructions. When the skeletal system is adequately supported with symmetrical muscle strength and especially over the top line, the animal is better equipped to use his body efficiently.

Weight & Ability of the Rider will determine how much pressure is put against the animal and how much resistance it will cause. Even though mules can carry proportionately more weight than a horse of the same size, this doesn’t mean you can indiscriminately weight them down until their knees are shaking. Be fair and responsible and do your part in the relationship. Do not expect the animal to carry an obviously overweight body that doesn’t know how to control itself! Learn to ride a balanced seat and practice the basics EVERY TIME YOU RIDE!

Participate in training activities that prepare you both, first with Groundwork and later under saddle. ALWAYS FOLLOW BASIC GROUNDWORK RULES for Leading, Lunging and Ground Driving! When Leading the equine, learn to hold the lead rope in your LEFT hand, keep his head at your shoulder, match your steps with his front legs, point in the direction of travel with your right hand and look where you are going. Walk straight lines, gradual arcs and square him up with equal weight over all four feet EVERY TIME you stop.

Participate in training activities that prepare you both, first with Groundwork and later under saddle. ALWAYS FOLLOW BASIC GROUNDWORK RULES for Leading, Lunging and Ground Driving! When Leading the equine, learn to hold the lead rope in your LEFT hand, keep his head at your shoulder, match your steps with his front legs, point in the direction of travel with your right hand and look where you are going. Walk straight lines, gradual arcs and square him up with equal weight over all four feet EVERY TIME you stop.

We are building NEW habits in their way of moving and the only way THAT can change is through routine, consistency in the routine and correctness in the execution of the exercises. Since this also requires that you be in good posture as well, you will also reap the benefits from this regimen. It is important to lead this way because if you carrying the lead rope in your hand closest to the halter, it will not promote self-body carriage in the equine. With every step you take, your hand moves (however slightly) to the right and left, and this will adversely affect his balance. Remember, that equines balance with their head and neck!

When Ground Driving, let your steps and hands follow the hind legs. Along with feeding correctly (as described), these exercises will help equines to drop fat rolls, to begin to take on a more correct shape and they will become strong in good posture. Learning to WALK in sync with your equine during Groundwork will make it easier for you to RIDE in sync with your equine.

Correct saddle placement is critical for the comfort and freedom of movement for your equine. The saddle should be placed over the center of balance, in the MIDDLE of the equine’s back, well behind the shoulder blade. Putting the saddle on a Longears is not the same as putting the saddle on a horse, or pony. Longears have a steeper angle at the shoulder and putting the saddle directly behind the withers as you do on a horse with a 45 degree angle (that sets the saddle further back), will position the saddle too close to the shoulder blade. The saddle should sit well behind the withers on a Longears and clear the shoulder blades to allow for maximum range of motion, proper balance and to prevent galling of the sensitive skin underneath and in front of the girth area just behind the forearms. It will help you know where to place the saddle if you just think about placing it in the middle of their back, then run your arm through the gullet under the saddle blanket, or pad, to allow for air flow over the spine. One way to tell if your saddle is placed correctly is to notice where your girth is hanging. Make sure that the girth is hanging 3-4 inches (about a palm’s width) behind the forearm and not right behind the forearm where the skin is thinner and more sensitive. This position is where the belly begins to swell and the skin is thicker.

Correct saddle placement is critical for the comfort and freedom of movement for your equine. The saddle should be placed over the center of balance, in the MIDDLE of the equine’s back, well behind the shoulder blade. Putting the saddle on a Longears is not the same as putting the saddle on a horse, or pony. Longears have a steeper angle at the shoulder and putting the saddle directly behind the withers as you do on a horse with a 45 degree angle (that sets the saddle further back), will position the saddle too close to the shoulder blade. The saddle should sit well behind the withers on a Longears and clear the shoulder blades to allow for maximum range of motion, proper balance and to prevent galling of the sensitive skin underneath and in front of the girth area just behind the forearms. It will help you know where to place the saddle if you just think about placing it in the middle of their back, then run your arm through the gullet under the saddle blanket, or pad, to allow for air flow over the spine. One way to tell if your saddle is placed correctly is to notice where your girth is hanging. Make sure that the girth is hanging 3-4 inches (about a palm’s width) behind the forearm and not right behind the forearm where the skin is thinner and more sensitive. This position is where the belly begins to swell and the skin is thicker.

The saddle can easily slip forward if not secured with a crupper snugly fit to the tail with a solid D-ring attached to your Western, English or Side Saddle. If you are using an English or Side Saddle, in order to attach the crupper, you can use a metal “T” that slides underneath the seat between the two sides of the padding. Chafing of the tail from the crupper can be prevented by making sure it is snug, but not too tight, or too loose. When you use a sparing amount of Johnson’s baby oil in the mane and tail during grooming, it will keep the skin underneath the tail from chafing. Johnson’s Baby oil will also prevent equines from chewing on each others’ tails. Mules generally have more swell to their barrels to stop a saddle from sliding backwards than horses. For this reason, Longears will not necessarily need a breast collar (but they do look prettier when the rigging is balanced for a parade!).

The saddle can easily slip forward if not secured with a crupper snugly fit to the tail with a solid D-ring attached to your Western, English or Side Saddle. If you are using an English or Side Saddle, in order to attach the crupper, you can use a metal “T” that slides underneath the seat between the two sides of the padding. Chafing of the tail from the crupper can be prevented by making sure it is snug, but not too tight, or too loose. When you use a sparing amount of Johnson’s baby oil in the mane and tail during grooming, it will keep the skin underneath the tail from chafing. Johnson’s Baby oil will also prevent equines from chewing on each others’ tails. Mules generally have more swell to their barrels to stop a saddle from sliding backwards than horses. For this reason, Longears will not necessarily need a breast collar (but they do look prettier when the rigging is balanced for a parade!).

A breast collar can actually be counterproductive when trail riding. It will tend to pull the saddle forward and closer to the withers This would be out of alignment with the center of gravity on a Longears. Before you mount, ask your equine to stretch his front legs forward, one at a time, to clear any skin that could get creased under the girth area and to help the girth to lie flat against the skin. I prefer using string girths with all my saddles (English & Side Saddles included). They tend to lie flatter and allow for adequate air circulation and free movement to prevent excessive sweating that can cause chafing in that area.

If you have given attention to all the details necessary to make sure your equine is comfortable in his tack and equipment, and if he has been privy to all the Groundwork necessary for strong and balanced postural core strength, then mounting should never be an issue at all. He will possess the strength to hold fast to his good equine posture when standing still and your tack and equipment should not shift and make him want to move. Equines become disobedient when they experience a loss of balance. When your equine is slowly and adequately prepared to carry a rider, or pull a vehicle, you are better able to enjoy your time together!

If you have given attention to all the details necessary to make sure your equine is comfortable in his tack and equipment, and if he has been privy to all the Groundwork necessary for strong and balanced postural core strength, then mounting should never be an issue at all. He will possess the strength to hold fast to his good equine posture when standing still and your tack and equipment should not shift and make him want to move. Equines become disobedient when they experience a loss of balance. When your equine is slowly and adequately prepared to carry a rider, or pull a vehicle, you are better able to enjoy your time together!

Losses of balance can occur under a variety of circumstances. Paying attention to all the details in preparation for riding that I have described here will prevent most situations where the equine can suffer a loss of balance. Strong postural core strength can allow the equine to stand still while you mount and prevent his moving or running off when being mounted. Yes, you can teach him to sidle over to the fence or a mounting block, but that won’t help you on the trail! A strong and balanced equine with adequate core strength and good posture will be a calm and more confident companion. He will be happy to oblige your every command because he CAN do what you ask!

To learn more about Meredith Hodges and her comprehensive all-breed equine training program, visit LuckyThreeRanch.com, MEREDITH HODGES PUBLIC FIGURE Facebook page, or call 1-800-816-7566. Check out her children’s website at JasperTheMule.com. Also, find Meredith on Pinterest, Instagram, MeWe, YouTube and Twitter.

Covered in TRAINING MULES & DONKEY: A LOGICAL APPROACH TO TRAINING, TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE, EQUUS REVISITED and A GUIDE TO RAISING & SHOWING MULES at www.luckythreeranchstore.com.

© 2013, 2016, 2024 Lucky Three Ranch, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

What kind of equine handler are you? When interacting with your Longears or any equine, are you an observer or a participant? Are you fully aware of the reasons for your equine’s behaviors? Behavior in general is most often motivated by a stimulus that elicits a response, yet the early years of physiological development are most dependent on heredity. Heredity includes not only physical characteristics, but mental, emotional and instinctual behaviors as well. We are taught that if an equine’s knees are beginning to fuse, he is ready for training. Is the animal really ready for training just because his knees are beginning to fuse? Physical development is called maturation, and we often determine the equine’s capabilities by maturation alone, with no consideration for the whole animal.

What kind of equine handler are you? When interacting with your Longears or any equine, are you an observer or a participant? Are you fully aware of the reasons for your equine’s behaviors? Behavior in general is most often motivated by a stimulus that elicits a response, yet the early years of physiological development are most dependent on heredity. Heredity includes not only physical characteristics, but mental, emotional and instinctual behaviors as well. We are taught that if an equine’s knees are beginning to fuse, he is ready for training. Is the animal really ready for training just because his knees are beginning to fuse? Physical development is called maturation, and we often determine the equine’s capabilities by maturation alone, with no consideration for the whole animal. When the stallion signals danger, it is this mare that will lead the herd, while the stallion generally brings up the rear. During estrus, the mare cycles every 21 days during the warmer months of the year. The mare accepts the stallion for only seven days out of the 21-day cycle. The stallion may cover her several times during that period and will do the same with the other mares in the herd. Not all mares will accept the advances of the stallion at certain times and, because they are as different as people are in their genetic makeup, not all of them will become pregnant every time.

When the stallion signals danger, it is this mare that will lead the herd, while the stallion generally brings up the rear. During estrus, the mare cycles every 21 days during the warmer months of the year. The mare accepts the stallion for only seven days out of the 21-day cycle. The stallion may cover her several times during that period and will do the same with the other mares in the herd. Not all mares will accept the advances of the stallion at certain times and, because they are as different as people are in their genetic makeup, not all of them will become pregnant every time. A mule will pin its ears when it is concentrating very hard and when it is following you and wants attention. Mules and donkeys are basically very friendly and rarely lay their ears flat back in pure anger like a horse will. When they are angry, you will know it. Scratching in different areas will produce different results. If you scratch their jowls, for instance, they may perk their ears forward, but when you rub their forehead, they will lay their ears back. If you scratch the insides of the ears, some will like it and tilt the head sideways with quivering eyebrows while others will jerk away at your impolite intrusion.

A mule will pin its ears when it is concentrating very hard and when it is following you and wants attention. Mules and donkeys are basically very friendly and rarely lay their ears flat back in pure anger like a horse will. When they are angry, you will know it. Scratching in different areas will produce different results. If you scratch their jowls, for instance, they may perk their ears forward, but when you rub their forehead, they will lay their ears back. If you scratch the insides of the ears, some will like it and tilt the head sideways with quivering eyebrows while others will jerk away at your impolite intrusion. At first, Arabian horses were thought to be silly and difficult—not the ideal mount for the common man. Later, the intelligence of the Arabian was discovered and explained by saying that, because the Arabian’s eyes are set lower in the head and the forehead is broader than most other equines, there is more brain space in the skull. This is also true of most mules and, particularly, Arabian mules. Once man believed in the equine’s intelligence and had a scientific reason for it, training was modified and approached a little differently. Man was then able to learn even more about the horses he was training. It wasn’t long before man discovered that this didn’t always hold true and there had to be more to consider when assessing the whole human being and, consequently, the whole horse.

At first, Arabian horses were thought to be silly and difficult—not the ideal mount for the common man. Later, the intelligence of the Arabian was discovered and explained by saying that, because the Arabian’s eyes are set lower in the head and the forehead is broader than most other equines, there is more brain space in the skull. This is also true of most mules and, particularly, Arabian mules. Once man believed in the equine’s intelligence and had a scientific reason for it, training was modified and approached a little differently. Man was then able to learn even more about the horses he was training. It wasn’t long before man discovered that this didn’t always hold true and there had to be more to consider when assessing the whole human being and, consequently, the whole horse.

My favorite holiday of the year has always been Christmas! The sights, sounds and smells of Christmas transport me to a magical place for the whole month of December, and the excitement and joy of yesterday still ring true today. I cannot think of a more deserving holiday than one that celebrates the birth of Jesus Christ and promotes so much hope and serenity throughout the world, if only for a day. Christmas reminds us all that the spirit of sharing and giving is timeless and takes only a willing attitude and a little bit of creativity.

My favorite holiday of the year has always been Christmas! The sights, sounds and smells of Christmas transport me to a magical place for the whole month of December, and the excitement and joy of yesterday still ring true today. I cannot think of a more deserving holiday than one that celebrates the birth of Jesus Christ and promotes so much hope and serenity throughout the world, if only for a day. Christmas reminds us all that the spirit of sharing and giving is timeless and takes only a willing attitude and a little bit of creativity. watched a 1955 film called On The Twelfth Day of Christmas. As you might guess, it was based on the old English song, “The Twelve Days of Christmas.” Every year, the film brought wild bursts of laughter, as we watched a proper Edwardian lady’s townhouse in England become filled to overflowing with gifts from her suitor. Not only did she get the gift designated for each day, but also the same gifts from prior days plus the new one. By Christmas, her little townhouse was filled with 12 partridges in pear trees, 22 turtle doves, 30 French hens, 36 calling birds, 25 gold rings, 30 geese a laying, 28 swans a swimming, 32 maids a milking, 27 ladies dancing, 30 Lords a leaping, 22 Pipers piping and 12 drummers drumming! Laughter filled our house daily from that day forward, all the way up to Christmas. Of course, as children, we were also reminded of the “naughty and nice” list.

watched a 1955 film called On The Twelfth Day of Christmas. As you might guess, it was based on the old English song, “The Twelve Days of Christmas.” Every year, the film brought wild bursts of laughter, as we watched a proper Edwardian lady’s townhouse in England become filled to overflowing with gifts from her suitor. Not only did she get the gift designated for each day, but also the same gifts from prior days plus the new one. By Christmas, her little townhouse was filled with 12 partridges in pear trees, 22 turtle doves, 30 French hens, 36 calling birds, 25 gold rings, 30 geese a laying, 28 swans a swimming, 32 maids a milking, 27 ladies dancing, 30 Lords a leaping, 22 Pipers piping and 12 drummers drumming! Laughter filled our house daily from that day forward, all the way up to Christmas. Of course, as children, we were also reminded of the “naughty and nice” list. Christmas baking for days on end with my Grandma is a favorite memory. We got to bake great gifts for many friends and family members (and we all knew there would be time to exercise and take off the weight…LATER!). We children were wide-eyed and filled with wonder as we passed the evenings listening to our favorite Christmas carols and our elders’ stories of Christmases past. And we absolutely knew that Santa really could drive eight tiny reindeer across the sky, with Rudolph lighting the way with his red nose, bringing presents to little children all over the world. All of these experiences bonded our entire family together.

Christmas baking for days on end with my Grandma is a favorite memory. We got to bake great gifts for many friends and family members (and we all knew there would be time to exercise and take off the weight…LATER!). We children were wide-eyed and filled with wonder as we passed the evenings listening to our favorite Christmas carols and our elders’ stories of Christmases past. And we absolutely knew that Santa really could drive eight tiny reindeer across the sky, with Rudolph lighting the way with his red nose, bringing presents to little children all over the world. All of these experiences bonded our entire family together. We kids always awoke extremely early on Christmas Day, bouncing down the stairs to see what Santa had left us. The cookies and milk were gone and the presents from Santa were under the tree, but we were not allowed to touch them until our parents and grandparents got up. That wait was excruciating, but it was oh so much fun when the adults finally got up! After opening presents, everyone had a light breakfast, because the early afternoon would bring our traditional Christmas dinner with friends and family. My mother made the most amazing spread of perfectly roasted turkey and stuffing, mashed potatoes and gravy, an incredible salad filled with everything you can think of from the garden, sweet potatoes and a lovely cranberry sauce. The meal was always topped off by my grandmother’s unique and decadent chocolate roll, a light chocolate cake with real whipped cream and homemade chocolate sauce on top.

We kids always awoke extremely early on Christmas Day, bouncing down the stairs to see what Santa had left us. The cookies and milk were gone and the presents from Santa were under the tree, but we were not allowed to touch them until our parents and grandparents got up. That wait was excruciating, but it was oh so much fun when the adults finally got up! After opening presents, everyone had a light breakfast, because the early afternoon would bring our traditional Christmas dinner with friends and family. My mother made the most amazing spread of perfectly roasted turkey and stuffing, mashed potatoes and gravy, an incredible salad filled with everything you can think of from the garden, sweet potatoes and a lovely cranberry sauce. The meal was always topped off by my grandmother’s unique and decadent chocolate roll, a light chocolate cake with real whipped cream and homemade chocolate sauce on top. original farmhouse at Lucky Three Ranch, the old floors were sturdier than those in my present home, so the mules were actually allowed to help with the decorating of the Christmas tree!

original farmhouse at Lucky Three Ranch, the old floors were sturdier than those in my present home, so the mules were actually allowed to help with the decorating of the Christmas tree! my mules, horses and donkeys became an integral part of each holiday season. My favorite tradition now is the time spent sharing a warm hug with each of my equines and giving them an extra measure of oats on that very special day that we call Christmas!

my mules, horses and donkeys became an integral part of each holiday season. My favorite tradition now is the time spent sharing a warm hug with each of my equines and giving them an extra measure of oats on that very special day that we call Christmas!

By Meredith Hodges

By Meredith Hodges Feeding: When developing the equine’s body, it is important to know what feeds are the healthiest for him. There are lots of different ways to feed your equines today, but I have found a regimen that works best. I did this through constant and continual research using a field study for more than 50 years with 32 equines of varying breeds, types and sizes.

Feeding: When developing the equine’s body, it is important to know what feeds are the healthiest for him. There are lots of different ways to feed your equines today, but I have found a regimen that works best. I did this through constant and continual research using a field study for more than 50 years with 32 equines of varying breeds, types and sizes. Most equines on other kinds of feeding programs develop bodies with a protruding spine and a “hay belly” hanging from it. The shape is quite different from a balanced body with core strength. They have an indentation along both sides of the spine instead of having a spine that “melds” into the torso with uniform conformity. My feeding program produces an ideal body shape with ALL my equines with minimal exercise. The SHAPE of the animal’s body is important for the correct fit of the tack and equipment.

Most equines on other kinds of feeding programs develop bodies with a protruding spine and a “hay belly” hanging from it. The shape is quite different from a balanced body with core strength. They have an indentation along both sides of the spine instead of having a spine that “melds” into the torso with uniform conformity. My feeding program produces an ideal body shape with ALL my equines with minimal exercise. The SHAPE of the animal’s body is important for the correct fit of the tack and equipment.

The stirrups need to hang straight down over the center of balance on the equine, in the MIDDLE of his torso. Stirrups with Tapaderos can be safer that those without, but if the toes on your boots are too pointed and too long, they can actually hinder you from keeping your feet securely in the stirrups. You should never wear tennis shoes, or shoes with no heels, when riding. Ideally, your weight should be on the ball of your foot with the heel of your boot touching the back of the stirrup to keep your feet from sliding through the stirrups.

The stirrups need to hang straight down over the center of balance on the equine, in the MIDDLE of his torso. Stirrups with Tapaderos can be safer that those without, but if the toes on your boots are too pointed and too long, they can actually hinder you from keeping your feet securely in the stirrups. You should never wear tennis shoes, or shoes with no heels, when riding. Ideally, your weight should be on the ball of your foot with the heel of your boot touching the back of the stirrup to keep your feet from sliding through the stirrups. Localized pressure is particularly prevalent with sawbuck pack saddles. That is why you see so many pack mules with white spots at the withers…unbalanced loads that will shift. When the horn sits lower and the saddle pressure is spread across a wider area, the pressure is more comfortable for the animal and will not cause chafing. The saddle horn is another consideration. They are built in so many different ways, but a lot of those ways are cosmetic and often dangerous. Vaqueros that worked regularly with cattle and horses built their saddles with a thick and functional horn. The horns on a lot of saddles are built for function, but there are many that are simply cosmetically built. They are often too high and too narrow…a hazard if you happen to get thrown onto them.

Localized pressure is particularly prevalent with sawbuck pack saddles. That is why you see so many pack mules with white spots at the withers…unbalanced loads that will shift. When the horn sits lower and the saddle pressure is spread across a wider area, the pressure is more comfortable for the animal and will not cause chafing. The saddle horn is another consideration. They are built in so many different ways, but a lot of those ways are cosmetic and often dangerous. Vaqueros that worked regularly with cattle and horses built their saddles with a thick and functional horn. The horns on a lot of saddles are built for function, but there are many that are simply cosmetically built. They are often too high and too narrow…a hazard if you happen to get thrown onto them. Using the back girth to hold the saddle back might seem like a good idea, but it puts the pressure on the fragile undercarriage rib bones that can fracture easily. The under-carriage rib bones beneath a properly placed back girth are thicker and less likely to fracture under abrupt pressure. It can also cause too much pressure on the female genitals and small intestines, restricting optimal organ function. The rear girth should always be attached to the front girth underneath, hang perpendicular to the ground and should only be snug enough to keep the back of the saddle down.

Using the back girth to hold the saddle back might seem like a good idea, but it puts the pressure on the fragile undercarriage rib bones that can fracture easily. The under-carriage rib bones beneath a properly placed back girth are thicker and less likely to fracture under abrupt pressure. It can also cause too much pressure on the female genitals and small intestines, restricting optimal organ function. The rear girth should always be attached to the front girth underneath, hang perpendicular to the ground and should only be snug enough to keep the back of the saddle down. The shoulders on the equine are only attached with cartilage and need to be able to “float” freely forward with the legs through the front quarters when in motion. This means that the saddle should fit your equine like a glove and rigged so it cannot slide forward over the Shoulder Blades. When you sit on a horse bareback, your legs will find the “groove” right behind the shoulder blade.

The shoulders on the equine are only attached with cartilage and need to be able to “float” freely forward with the legs through the front quarters when in motion. This means that the saddle should fit your equine like a glove and rigged so it cannot slide forward over the Shoulder Blades. When you sit on a horse bareback, your legs will find the “groove” right behind the shoulder blade. They do not have as prominent withers and there is a muscle that is located right where your legs fall into the “groove” on a horse. Their torso is comprised of smooth muscle and is straighter across and more compact than that of the horse that possesses more bulk muscle. The natural tendency on a mule or donkey is for the saddle to slide FORWARD, into the shoulder blades. It is advisable to use cruppers or breeching to help the saddle stay stabilized.

They do not have as prominent withers and there is a muscle that is located right where your legs fall into the “groove” on a horse. Their torso is comprised of smooth muscle and is straighter across and more compact than that of the horse that possesses more bulk muscle. The natural tendency on a mule or donkey is for the saddle to slide FORWARD, into the shoulder blades. It is advisable to use cruppers or breeching to help the saddle stay stabilized. An animal with insufficient conditioning and balance will hollow his back and neck and try to compensate for his inefficiencies in muscle conditioning and movement. When the equine’s tack and equipment fit properly, the extremities have full range of motion so he can pick each step with confidence and no obstructions. When the skeletal system is adequately supported with symmetrical muscle strength and especially over the top line, the animal is better equipped to use his body efficiently.

An animal with insufficient conditioning and balance will hollow his back and neck and try to compensate for his inefficiencies in muscle conditioning and movement. When the equine’s tack and equipment fit properly, the extremities have full range of motion so he can pick each step with confidence and no obstructions. When the skeletal system is adequately supported with symmetrical muscle strength and especially over the top line, the animal is better equipped to use his body efficiently. Participate in training activities that prepare you both, first with Groundwork and later under saddle. ALWAYS FOLLOW BASIC GROUNDWORK RULES for Leading, Lunging and Ground Driving! When Leading the equine, learn to hold the lead rope in your LEFT hand, keep his head at your shoulder, match your steps with his front legs, point in the direction of travel with your right hand and look where you are going. Walk straight lines, gradual arcs and square him up with equal weight over all four feet EVERY TIME you stop.

Participate in training activities that prepare you both, first with Groundwork and later under saddle. ALWAYS FOLLOW BASIC GROUNDWORK RULES for Leading, Lunging and Ground Driving! When Leading the equine, learn to hold the lead rope in your LEFT hand, keep his head at your shoulder, match your steps with his front legs, point in the direction of travel with your right hand and look where you are going. Walk straight lines, gradual arcs and square him up with equal weight over all four feet EVERY TIME you stop.

Correct saddle placement is critical for the comfort and freedom of movement for your equine. The saddle should be placed over the center of balance, in the MIDDLE of the equine’s back, well behind the shoulder blade. Putting the saddle on a Longears is not the same as putting the saddle on a horse, or pony. Longears have a steeper angle at the shoulder and putting the saddle directly behind the withers as you do on a horse with a 45 degree angle (that sets the saddle further back), will position the saddle too close to the shoulder blade. The saddle should sit well behind the withers on a Longears and clear the shoulder blades to allow for maximum range of motion, proper balance and to prevent galling of the sensitive skin underneath and in front of the girth area just behind the forearms. It will help you know where to place the saddle if you just think about placing it in the middle of their back, then run your arm through the gullet under the saddle blanket, or pad, to allow for air flow over the spine. One way to tell if your saddle is placed correctly is to notice where your girth is hanging. Make sure that the girth is hanging 3-4 inches (about a palm’s width) behind the forearm and not right behind the forearm where the skin is thinner and more sensitive. This position is where the belly begins to swell and the skin is thicker.

Correct saddle placement is critical for the comfort and freedom of movement for your equine. The saddle should be placed over the center of balance, in the MIDDLE of the equine’s back, well behind the shoulder blade. Putting the saddle on a Longears is not the same as putting the saddle on a horse, or pony. Longears have a steeper angle at the shoulder and putting the saddle directly behind the withers as you do on a horse with a 45 degree angle (that sets the saddle further back), will position the saddle too close to the shoulder blade. The saddle should sit well behind the withers on a Longears and clear the shoulder blades to allow for maximum range of motion, proper balance and to prevent galling of the sensitive skin underneath and in front of the girth area just behind the forearms. It will help you know where to place the saddle if you just think about placing it in the middle of their back, then run your arm through the gullet under the saddle blanket, or pad, to allow for air flow over the spine. One way to tell if your saddle is placed correctly is to notice where your girth is hanging. Make sure that the girth is hanging 3-4 inches (about a palm’s width) behind the forearm and not right behind the forearm where the skin is thinner and more sensitive. This position is where the belly begins to swell and the skin is thicker. The saddle can easily slip forward if not secured with a crupper snugly fit to the tail with a solid D-ring attached to your Western, English or Side Saddle. If you are using an English or Side Saddle, in order to attach the crupper, you can use a metal “T” that slides underneath the seat between the two sides of the padding. Chafing of the tail from the crupper can be prevented by making sure it is snug, but not too tight, or too loose. When you use a sparing amount of Johnson’s baby oil in the mane and tail during grooming, it will keep the skin underneath the tail from chafing. Johnson’s Baby oil will also prevent equines from chewing on each others’ tails. Mules generally have more swell to their barrels to stop a saddle from sliding backwards than horses. For this reason, Longears will not necessarily need a breast collar (but they do look prettier when the rigging is balanced for a parade!).

The saddle can easily slip forward if not secured with a crupper snugly fit to the tail with a solid D-ring attached to your Western, English or Side Saddle. If you are using an English or Side Saddle, in order to attach the crupper, you can use a metal “T” that slides underneath the seat between the two sides of the padding. Chafing of the tail from the crupper can be prevented by making sure it is snug, but not too tight, or too loose. When you use a sparing amount of Johnson’s baby oil in the mane and tail during grooming, it will keep the skin underneath the tail from chafing. Johnson’s Baby oil will also prevent equines from chewing on each others’ tails. Mules generally have more swell to their barrels to stop a saddle from sliding backwards than horses. For this reason, Longears will not necessarily need a breast collar (but they do look prettier when the rigging is balanced for a parade!). If you have given attention to all the details necessary to make sure your equine is comfortable in his tack and equipment, and if he has been privy to all the Groundwork necessary for strong and balanced postural core strength, then mounting should never be an issue at all. He will possess the strength to hold fast to his good equine posture when standing still and your tack and equipment should not shift and make him want to move. Equines become disobedient when they experience a loss of balance. When your equine is slowly and adequately prepared to carry a rider, or pull a vehicle, you are better able to enjoy your time together!

If you have given attention to all the details necessary to make sure your equine is comfortable in his tack and equipment, and if he has been privy to all the Groundwork necessary for strong and balanced postural core strength, then mounting should never be an issue at all. He will possess the strength to hold fast to his good equine posture when standing still and your tack and equipment should not shift and make him want to move. Equines become disobedient when they experience a loss of balance. When your equine is slowly and adequately prepared to carry a rider, or pull a vehicle, you are better able to enjoy your time together!

By Meredith Hodges

By Meredith Hodges Of course, in order to enjoy Winter games and sports, you must first be sure to dress appropriately for the weather in your area. If you live in a cool or cold climate, dress in layered clothing you can easily remove if you need to. Wear a hat to conserve your body heat and footwear that keeps your feet warm and dry. What your equine wears in cold weather is equally important. For instance, if your equine’s winter coat tends to be on the thinner side, he may need a blanket for the long Winter nights to keep his body from expending too much energy just trying to stay warm. The blanket will also serve to mat down his coat so there is less chance of it becoming entangled in his tack or harness. If you have a stall for your equine, just for Winter months, you may want to trace-clip him in the areas that do the most sweating so that when he is worked, he will cool down quickly and easily. Promoting good circulation keeps your equine warm, helps his body to stay flexible and supple, and cuts way down on his muscle and bone stiffness. Be sure to begin any and all workouts and recreational activities with consistent and appropriate warm-up exercises.

Of course, in order to enjoy Winter games and sports, you must first be sure to dress appropriately for the weather in your area. If you live in a cool or cold climate, dress in layered clothing you can easily remove if you need to. Wear a hat to conserve your body heat and footwear that keeps your feet warm and dry. What your equine wears in cold weather is equally important. For instance, if your equine’s winter coat tends to be on the thinner side, he may need a blanket for the long Winter nights to keep his body from expending too much energy just trying to stay warm. The blanket will also serve to mat down his coat so there is less chance of it becoming entangled in his tack or harness. If you have a stall for your equine, just for Winter months, you may want to trace-clip him in the areas that do the most sweating so that when he is worked, he will cool down quickly and easily. Promoting good circulation keeps your equine warm, helps his body to stay flexible and supple, and cuts way down on his muscle and bone stiffness. Be sure to begin any and all workouts and recreational activities with consistent and appropriate warm-up exercises. Since most inclement weather produces slippery ground surfaces, if your equine is to be used extensively, it is important that he have appropriate shoes on his feet during the slippery seasons. On strictly muddy or slippery surfaces, tapping and drilling studs into his shoes can help immensely in giving him added traction. If cared for properly, you can remove these studs when you don’t need them. If you get snow in your area, you may want to go with borium shoes and rim pads. The borium shoes supply good traction, while the rim pads prevent snow from balling up in your equine’s feet. I also suggest using splint boots on all four of his legs. This will protect against injury and give him added support and protection of his fetlock joints.

Since most inclement weather produces slippery ground surfaces, if your equine is to be used extensively, it is important that he have appropriate shoes on his feet during the slippery seasons. On strictly muddy or slippery surfaces, tapping and drilling studs into his shoes can help immensely in giving him added traction. If cared for properly, you can remove these studs when you don’t need them. If you get snow in your area, you may want to go with borium shoes and rim pads. The borium shoes supply good traction, while the rim pads prevent snow from balling up in your equine’s feet. I also suggest using splint boots on all four of his legs. This will protect against injury and give him added support and protection of his fetlock joints. The better trained your equine is, the more possibilities there are for Winter sports and games. If the idea of taking lessons at a riding stable that has an indoor arena appeals to you, Winter tends to be a less hectic, more peaceful time of year in which to learn and practice without the added stress and anxiety of showing and other warm weather activities. But even if you want to forego the lessons, there are numerous stables that will rent the use of their indoor arenas for a nominal fee and there are places to trail ride through beautiful Winter scenes. People and equines alike seem to derive great pleasure from these Winter get-togethers when they are carefully and responsibly planned.

The better trained your equine is, the more possibilities there are for Winter sports and games. If the idea of taking lessons at a riding stable that has an indoor arena appeals to you, Winter tends to be a less hectic, more peaceful time of year in which to learn and practice without the added stress and anxiety of showing and other warm weather activities. But even if you want to forego the lessons, there are numerous stables that will rent the use of their indoor arenas for a nominal fee and there are places to trail ride through beautiful Winter scenes. People and equines alike seem to derive great pleasure from these Winter get-togethers when they are carefully and responsibly planned. Another great way to have fun with your equine is participating in Winter games and holiday parades. Christmas is always a joyous time to bring your equine out of the barn. Consider decorating your equine, dressing up yourself and then riding or driving in your local Christmas parade. This can be loads of fun! Caroling aboard your equine throughout your neighborhood is also a wonderful way for you, your equine and your neighbors to get into the holiday spirit. Oftentimes when my equines and I have gone out caroling after a Christmas parade, the neighborhood children have come out to sing and dance behind our caroling caravan! This kind of pure joy is contagious and always reminds me of the true meaning of the Christmas season.

Another great way to have fun with your equine is participating in Winter games and holiday parades. Christmas is always a joyous time to bring your equine out of the barn. Consider decorating your equine, dressing up yourself and then riding or driving in your local Christmas parade. This can be loads of fun! Caroling aboard your equine throughout your neighborhood is also a wonderful way for you, your equine and your neighbors to get into the holiday spirit. Oftentimes when my equines and I have gone out caroling after a Christmas parade, the neighborhood children have come out to sing and dance behind our caroling caravan! This kind of pure joy is contagious and always reminds me of the true meaning of the Christmas season.

Consider, for instance, the bridle, which is such an important communication device. Do not select a harsh bit for control. Control comes from logical and sequential practices during training and not from force. The bit should be comfortable and be fitted correctly to facilitate good communication from your hands to the corners of your equine’s mouth. The bit should also be a comfortable width, leaving a half-inch from the hinge on both sides of his mouth. If the bit is placed too high or too low in the animal’s mouth, his fussing while he tries to get comfortable will override his ability to receive clear communication from your hands. NOTE: Be sure the chin chain on a curb bit lies flat and allows for two fingers to fit easily between the chain and his jaw.

Consider, for instance, the bridle, which is such an important communication device. Do not select a harsh bit for control. Control comes from logical and sequential practices during training and not from force. The bit should be comfortable and be fitted correctly to facilitate good communication from your hands to the corners of your equine’s mouth. The bit should also be a comfortable width, leaving a half-inch from the hinge on both sides of his mouth. If the bit is placed too high or too low in the animal’s mouth, his fussing while he tries to get comfortable will override his ability to receive clear communication from your hands. NOTE: Be sure the chin chain on a curb bit lies flat and allows for two fingers to fit easily between the chain and his jaw. Although the mule is a tough and durable animal, there are places on his body where his skin is particularly sensitive and easily chafed, so when fitting a harness or saddle you must pay special attention to these parts of his body. The collar on a harness, for example, needs to fit snugly and smoothly in front of the shoulders, allowing your hand to slip easily between the collar and the base of your mule’s throat and chest. A collar that is either too tight or too loose can rub and cause soreness, inhibiting maximum performance. When improperly adjusted, a breast collar harness can also cause rubbing at the points of the shoulders.

Although the mule is a tough and durable animal, there are places on his body where his skin is particularly sensitive and easily chafed, so when fitting a harness or saddle you must pay special attention to these parts of his body. The collar on a harness, for example, needs to fit snugly and smoothly in front of the shoulders, allowing your hand to slip easily between the collar and the base of your mule’s throat and chest. A collar that is either too tight or too loose can rub and cause soreness, inhibiting maximum performance. When improperly adjusted, a breast collar harness can also cause rubbing at the points of the shoulders. material is used for the girth on your harness or saddle. This may also be true in the case of the breeching and the crupper. The cleanliness, correct adjustment and comfort of the harness, saddle and other equipment can actually be a matter of safety for both you and your animal.

material is used for the girth on your harness or saddle. This may also be true in the case of the breeching and the crupper. The cleanliness, correct adjustment and comfort of the harness, saddle and other equipment can actually be a matter of safety for both you and your animal. In the past, saddles were constructed to accommodate the physiques of the horses of that time. Over the years, as training programs for mules have evolved and begun to correctly build muscle for equine activities. Saddle makers have also evolved, and now specialize in the construction of saddles that are tailored to the physical differences of individual equines. Saddle trees are now made with different widths and lengths of the bars in the tree, and even different materials are being used to make the trees, allowing for more flexibility and a better fit. Since the mule is structurally different from any horse, it is even more important to carefully consider your choice of saddle for your mule. Saddle makers now make custom saddles with specially designed trees with “mule bars,” but these are not standard and should be fitted to the conformation of the individual mule, with consideration given to the activity for which he will be used. Although they may appear more comfortable, beware of saddles with trees that may be too flexible, as they do not offer the solid foundation to support an unbalanced rider on a poorly conditioned animal. Often, a saddle can be found that will closely fit your animal, and can be made to fit even better with the addition of extra and/or specialized pads, breast collars, breeching or cruppers. However, with extended use, you may find that these simple modifications are inadequate. An equine’s shape will change with physical conditioning and, as the level of performance is increased, it becomes increasingly more important to have equipment that fits properly, affords comfort and lends support.

In the past, saddles were constructed to accommodate the physiques of the horses of that time. Over the years, as training programs for mules have evolved and begun to correctly build muscle for equine activities. Saddle makers have also evolved, and now specialize in the construction of saddles that are tailored to the physical differences of individual equines. Saddle trees are now made with different widths and lengths of the bars in the tree, and even different materials are being used to make the trees, allowing for more flexibility and a better fit. Since the mule is structurally different from any horse, it is even more important to carefully consider your choice of saddle for your mule. Saddle makers now make custom saddles with specially designed trees with “mule bars,” but these are not standard and should be fitted to the conformation of the individual mule, with consideration given to the activity for which he will be used. Although they may appear more comfortable, beware of saddles with trees that may be too flexible, as they do not offer the solid foundation to support an unbalanced rider on a poorly conditioned animal. Often, a saddle can be found that will closely fit your animal, and can be made to fit even better with the addition of extra and/or specialized pads, breast collars, breeching or cruppers. However, with extended use, you may find that these simple modifications are inadequate. An equine’s shape will change with physical conditioning and, as the level of performance is increased, it becomes increasingly more important to have equipment that fits properly, affords comfort and lends support.

t the top that just catches through a four-inch sleeve on the post wing. It is easy to reach over the top for opening.

t the top that just catches through a four-inch sleeve on the post wing. It is easy to reach over the top for opening.

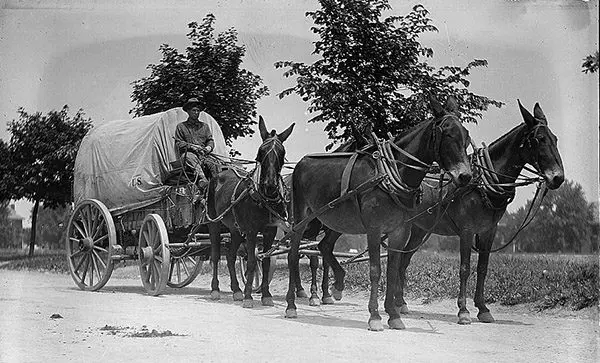

During the surge westward, heavy Conestoga wagons laden with all the possessions one could carry were often pulled by teams of mules that were either leased or owned by the early settlers. When cattlemen developed breeds like Texas Longhorns that could endure the harsh climate of the Great Plains, their mules pulled the chuck wagons that followed the large herds as they were driven the long distances to market. Improved farm equipment beckoned farmers to tame the West and what else could manage the vast land and long work hours save the mule? During these times, little thought was given to the possibility that this coveted land was already occupied by numerous Indian tribes.

During the surge westward, heavy Conestoga wagons laden with all the possessions one could carry were often pulled by teams of mules that were either leased or owned by the early settlers. When cattlemen developed breeds like Texas Longhorns that could endure the harsh climate of the Great Plains, their mules pulled the chuck wagons that followed the large herds as they were driven the long distances to market. Improved farm equipment beckoned farmers to tame the West and what else could manage the vast land and long work hours save the mule? During these times, little thought was given to the possibility that this coveted land was already occupied by numerous Indian tribes. The American government purchased many mules that were two and three years old—entirely too young for use. If they had purchased mules all over the age of four, it would have saved a lot of heartache and expense. Contractors and inspectors seemed to be more concerned with the numbers they could sell to the government than the quality and usefulness of the animals. When purchased for use, this invariably resulted in the mules being put onto a train with teamsters who knew nothing of their character. Those who know mules know the deep affection they develop for human beings with whom they spend much time. Thousands of young mules were rendered useless by the government’s incompetence and ignorance as to their maintenance and training.

The American government purchased many mules that were two and three years old—entirely too young for use. If they had purchased mules all over the age of four, it would have saved a lot of heartache and expense. Contractors and inspectors seemed to be more concerned with the numbers they could sell to the government than the quality and usefulness of the animals. When purchased for use, this invariably resulted in the mules being put onto a train with teamsters who knew nothing of their character. Those who know mules know the deep affection they develop for human beings with whom they spend much time. Thousands of young mules were rendered useless by the government’s incompetence and ignorance as to their maintenance and training. The Indians adopted the Spanish way of packing, as the Spaniards were noted experts. The Americans developed their own American pack saddle, but it was abandoned soon after its creation.

The Indians adopted the Spanish way of packing, as the Spaniards were noted experts. The Americans developed their own American pack saddle, but it was abandoned soon after its creation. In 1942, while in the service of the U.S. Army, Art Beaman became familiar with mules in a most curious way. He was working as an Operations Sergeant for a Headquarters in Northern California that determined whether troops were ready for combat. The troops consisted of 204 enlisted men, two veterinarian officers, four horses and 200 mules. Being a non-rider, Art was on and off his horse three times in the first ten minutes of the trip into the mountains. The First Sergeant finally decided to put him on a mule and open his eyes to the redeeming qualities of his mount. The next day, Art was able to say, “That mule and I were really a team…by this time, I trusted my mule so completely that I could have stood up and sang the national anthem as we slipped and skidded along!”

In 1942, while in the service of the U.S. Army, Art Beaman became familiar with mules in a most curious way. He was working as an Operations Sergeant for a Headquarters in Northern California that determined whether troops were ready for combat. The troops consisted of 204 enlisted men, two veterinarian officers, four horses and 200 mules. Being a non-rider, Art was on and off his horse three times in the first ten minutes of the trip into the mountains. The First Sergeant finally decided to put him on a mule and open his eyes to the redeeming qualities of his mount. The next day, Art was able to say, “That mule and I were really a team…by this time, I trusted my mule so completely that I could have stood up and sang the national anthem as we slipped and skidded along!” Those who have experienced the spiritual connection with mules all have their own individual stories to tell. From The Black Mule of Aveluy, by Charles G.D. Roberts, comes one of the most amazing World War I battlefield stories I’ve ever heard. It is the story of a man and a big black mule on a rain-scourged battlefield. “The mule lines of Aveluy were restless and unsteady under the tormented dark. All day long a six-inch high-velocity gun firing at irregular intervals from somewhere on the low ridge beyond the Ancre, had been feeling for them. Those terrible swift shells, which travel so fast on their flat trajectory that their bedlam shriek of warning and the rendering crash of their explosion seem to come in the same breathless instant, had tested the nerves of man and beast sufficiently during the daylight; but now, in the shifting obscurity of a young moon harrowed by driven cloudrack, their effect was yet more daunting.”

Those who have experienced the spiritual connection with mules all have their own individual stories to tell. From The Black Mule of Aveluy, by Charles G.D. Roberts, comes one of the most amazing World War I battlefield stories I’ve ever heard. It is the story of a man and a big black mule on a rain-scourged battlefield. “The mule lines of Aveluy were restless and unsteady under the tormented dark. All day long a six-inch high-velocity gun firing at irregular intervals from somewhere on the low ridge beyond the Ancre, had been feeling for them. Those terrible swift shells, which travel so fast on their flat trajectory that their bedlam shriek of warning and the rendering crash of their explosion seem to come in the same breathless instant, had tested the nerves of man and beast sufficiently during the daylight; but now, in the shifting obscurity of a young moon harrowed by driven cloudrack, their effect was yet more daunting.” Jimmy Wright remembered the blast and saw where he was. He was afraid his shoulder had been blown off, yet he could move both arms and discovered something was pulling on him. “He reached up his right arm—it was the left shoulder that was being tugged at—and encountered the furry head and ears of his rescuer! Reassured at the sound of his master’s voice, the big mule took his teeth out of Wright’s shoulder and began nuzzling solicitously at his sandy head.”

Jimmy Wright remembered the blast and saw where he was. He was afraid his shoulder had been blown off, yet he could move both arms and discovered something was pulling on him. “He reached up his right arm—it was the left shoulder that was being tugged at—and encountered the furry head and ears of his rescuer! Reassured at the sound of his master’s voice, the big mule took his teeth out of Wright’s shoulder and began nuzzling solicitously at his sandy head.”

George Washington was a fairly well educated man and, “the copybook which he transcribed at fourteen years of age a set of moral precepts or Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation was preserved.” Practical experience was the foundation for his best training in outdoor occupations and not books. He was a successful tobacco and livestock farmer early in his teens and mastered the art of surveying to plot the fields he inherited. It is no accident that George Washington became not only the father of our country, but also, the first organized mule breeder in America.