MULE CROSSING: Using Dressage Training with Mules

By Meredith Hodges

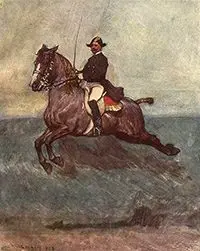

Why does Dressage training lend itself so well to training mules? In order to answer this question, we need to have a clear understanding of what Dressage really means and how it pertains to the mule’s mental and physical development in relationship to our own expectations. When most of us think of Dressage, we picture in our minds those elegant Lipizzaner stallions of the Spanish Riding School in Vienna, Austria.

Why does Dressage training lend itself so well to training mules? In order to answer this question, we need to have a clear understanding of what Dressage really means and how it pertains to the mule’s mental and physical development in relationship to our own expectations. When most of us think of Dressage, we picture in our minds those elegant Lipizzaner stallions of the Spanish Riding School in Vienna, Austria.

It’s easy to perceive Dressage as a more advanced form of Horsemanship, unless we realize that, in reality, it is the result of many years of intense training. It is also easy to believe that this is not the activity in which most of us see ourselves competing. Dressage requires much more well-developed skills from the rider, and the High School (known in Dressage by the French words Haute Ecole) movements exhibited are not generally used in the practical use of our animals. People may perceive these goals to be unattainable for the common horseman, and discard Dressage training for more commercial techniques that seem to give simpler and more immediate results in our English, Western and gaming mules. Surprisingly, a better understanding of the beginning levels of Dressage reveals that it is actually a preferred way to train, especially considering the mental and physical nature of mules.

At first glance, the Training Level patterns of Dressage may seem too simple to the average rider. (A Reining pattern is much more inviting because it is more stimulating and exciting.) However, Reining can be quite stressful—both mentally and physically—on a young mule unless he is brought along slowly and carefully. Because the mule is so strong and capable of running through any type of bridle arrangement, it’s best to avoid any confrontation that can cause resistance as much as possible.

I have found that my mules will exhibit resistant behavior when they are confused or frightened, but never out of “stubbornness.” Often, we take it for granted that, since a young mule can walk, trot, canter, back up, etc. by himself, he should be able to do all these things with us astride. What many people don’t realize is that mules are born with as diverse postures as humans, and there are few mules that will exhibit good equine posture without being constantly reminded. People compensate continually for deficiencies in their own body structure, and posture will vary from person to person and situation to situation. For example, a straight-backed chair will cause most of us to sit up straight, which is healthy for the spine and neck. On the other hand, the sinking comfort of a plush couch will produce a collapsed posture, which can eventually produce sore back and neck muscles. In a similar way, a mule will have to sacrifice his good posture to accommodate an unbalanced and inexperienced rider.

I have found that my mules will exhibit resistant behavior when they are confused or frightened, but never out of “stubbornness.” Often, we take it for granted that, since a young mule can walk, trot, canter, back up, etc. by himself, he should be able to do all these things with us astride. What many people don’t realize is that mules are born with as diverse postures as humans, and there are few mules that will exhibit good equine posture without being constantly reminded. People compensate continually for deficiencies in their own body structure, and posture will vary from person to person and situation to situation. For example, a straight-backed chair will cause most of us to sit up straight, which is healthy for the spine and neck. On the other hand, the sinking comfort of a plush couch will produce a collapsed posture, which can eventually produce sore back and neck muscles. In a similar way, a mule will have to sacrifice his good posture to accommodate an unbalanced and inexperienced rider.

In the simplicity of the Training Level patterns, you will be able to address the issue of good posture. This is when you can begin to condition the necessary muscles for maintaining good posture. In the Training Level Dressage patterns, a judge will always look for “a willing, obedient mount that moves forward freely, responds to the rider’s aids and accepts the bit.” Your mule will be encouraged to maintain the best possible equine posture for his individual stage of development while you practice the same. The simple patterns will enable you to minimize any loss of balance by either of you. As his muscles are strengthened and conditioned, your mule will be better able to carry his own body as well as yours. Only then should you begin to ask for more engagement in the hindquarters, which will eventually lead make more collection possible.

By taking the time to condition and strengthen their muscles, we allow our mules to engage in physical exercise that is not taxing and painful, thus, keeping their mental attitude fresh and happy. By conditioning your mule in a carefully sequenced pattern of exercises, you will more often avoid the possibility of throwing him off balance and into the confusion and fear that will lead to resistance and disobedience. With your own posture in mind, you can develop the rider and mule as one unit. The process is slow but thorough, and mutually satisfying.

By taking the time to condition and strengthen their muscles, we allow our mules to engage in physical exercise that is not taxing and painful, thus, keeping their mental attitude fresh and happy. By conditioning your mule in a carefully sequenced pattern of exercises, you will more often avoid the possibility of throwing him off balance and into the confusion and fear that will lead to resistance and disobedience. With your own posture in mind, you can develop the rider and mule as one unit. The process is slow but thorough, and mutually satisfying.

The Dressage saddle allows you the stability of a saddle, yet gives you the closest possible contact with your mule’s body (other than bareback), making your leg and seat aids clearer and more perceptible to your mule. With more clearly defined cues, the mule is better able to discern your wishes without fear or resistance. Western saddles are used more universally for training, but I believe that a lot of this is to accommodate riders with limited ability.

Equipment use plays an important part in the breaking saddle used, but many trainers today will agree that the less complicated equipment is used in the beginning, the better. The Western saddle may certainly be used for breaking but, from the mule’s standpoint, the Western saddle is heavier and there is quite a lot of leather between you and your mule, which can cause a certain amount of interference in communication. If the mule cannot “feel” his rider well, often times a leg or rein aid can come as a surprise and produce a response that is predisposed to resistance. For this reason, I prefer to start training in an all-purpose—or Dressage—saddle. However, I would recommend training in a Western saddle for the less-experienced rider, or if you are training a more easily excitable animal.

Equipment use plays an important part in the breaking saddle used, but many trainers today will agree that the less complicated equipment is used in the beginning, the better. The Western saddle may certainly be used for breaking but, from the mule’s standpoint, the Western saddle is heavier and there is quite a lot of leather between you and your mule, which can cause a certain amount of interference in communication. If the mule cannot “feel” his rider well, often times a leg or rein aid can come as a surprise and produce a response that is predisposed to resistance. For this reason, I prefer to start training in an all-purpose—or Dressage—saddle. However, I would recommend training in a Western saddle for the less-experienced rider, or if you are training a more easily excitable animal.

In Training Level Dressage, movements are limited to straight lines, simple transitions (i.e., walk to trot, trot to canter, canter to trot, trot to walk, and trot to walk to halt), and large 20-meter circles. This allows you to spend time working on rhythm, regularity and cadence in all three gaits, overall obedience to the aids, steadiness and learning to bend his body from head to tail through corners, while maintaining an upright posture. All this allows your mule the time to properly condition his muscles and to learn to stay between the aids in a comfortable and relaxing manner. He will also learn to move freely and easily forward, while the rider has time to develop his own muscles and perfect his own technique. Using this technique keeps stress at a minimum.

As in any exercise program, it is not advisable to drill and repeat every day. With a mule, as with any athlete, muscles need to be exercised and then allowed rest for a day or two between workouts to avoid serious injury. In between Dressage days, you can take your mule for a simple trail ride or just let him rest. The time-off and a variety of activities will keep him fresh and attentive. Three times a week is usually sufficient, with Dressage training for his proper development and conditioning, two days of simple hacking or trail riding and two days of rest. This also takes the pressure off of you. If you’re not into riding on a particular day, you won’t feel like you have to because your mule will retain his learning without the added stress of drilling day after day. Try to think of your mule’s training in terms of yourself: Would you care to be drilled to exhaustion day after day? How would you feel mentally and physically if you were? Dressage—whether it is basic or the most advanced—is a French word for training. It is thoughtful, considerate and kind, and will produce a mule that is mentally and physically capable of doing anything you might like to do with a relaxed and willing attitude. It may take a little longer, but the result speaks for itself.

As in any exercise program, it is not advisable to drill and repeat every day. With a mule, as with any athlete, muscles need to be exercised and then allowed rest for a day or two between workouts to avoid serious injury. In between Dressage days, you can take your mule for a simple trail ride or just let him rest. The time-off and a variety of activities will keep him fresh and attentive. Three times a week is usually sufficient, with Dressage training for his proper development and conditioning, two days of simple hacking or trail riding and two days of rest. This also takes the pressure off of you. If you’re not into riding on a particular day, you won’t feel like you have to because your mule will retain his learning without the added stress of drilling day after day. Try to think of your mule’s training in terms of yourself: Would you care to be drilled to exhaustion day after day? How would you feel mentally and physically if you were? Dressage—whether it is basic or the most advanced—is a French word for training. It is thoughtful, considerate and kind, and will produce a mule that is mentally and physically capable of doing anything you might like to do with a relaxed and willing attitude. It may take a little longer, but the result speaks for itself.

To learn more about Meredith Hodges and her comprehensive all-breed equine training program, visit LuckyThreeRanch.com, MEREDITH HODGES PUBLIC FIGURE Facebook page, or call 1-800-816-7566. Check out her children’s website at JasperTheMule.com. Also, find Meredith on Pinterest, Instagram, MeWe, YouTube and Twitter.

Covered in TRAINING MULES & DONKEY: A LOGICAL APPROACH TO TRAINING, TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE, EQUUS REVISITED and A GUIDE TO RAISING & SHOWING MULES at www.luckythreeranchstore.com.

© 2011, 2016, 2024 Lucky Three Ranch, Inc. All rights reserved.