By Meredith Hodges

By Meredith Hodges

A donkey jack can be your best friend or your worst enemy! Because he is a donkey, he possesses all the wonderful characteristics particular to donkeys—intelligence, strength, easy maintenance, suitability for many equine sports and, probably most important, an innate affectionate attitude. You must, however, realize that he is still an intact male, often governed by the hormones in his body. When nature takes over, the jack’s conscious thought is greatly diminished and he can become quite hazardous to your health. The jack’s aggressiveness is often masked by his sedate and affectionate attitude, but it can arise in a split second and do more damage than even a stallion. Usually, there is an awkwardness, or indecisiveness, in an agitated stallion that will allow you time to get out of the way, but the jack reacts strongly, swiftly and right on target, allowing you little or no time for retreat. By keeping a few simple things in mind, you can greatly reduce your chances of injury when handling jacks.

First, try to keep your jack in a comfortable atmosphere. Jacks can be great worriers, particularly about their mares and jennets. Ideally, you should keep the jack well out of sight and smell of the females, but this is not always practical. If he must be near females, make sure your  jack has a roomy area, free of refuse and debris, and adequately fenced. The fences should be high enough to discourage his leaning over the top and strong enough to bear his weight on impact. Also, they must be constructed so that there are no protrusions that could cause him injury. If females (or other animals) are present, the jack may run back and forth along the fence and catch his head on anything that is protruding. Hot wires along the inside of a weaker fence will often serve this purpose. However, a hot wire used alone is not sufficient. If your jack becomes frightened, he could run through an electric wire before he even knows that it is there. Giving him a clean, comfortable area where his limits are clearly defined will help him to be a calmer and more manageable animal.

jack has a roomy area, free of refuse and debris, and adequately fenced. The fences should be high enough to discourage his leaning over the top and strong enough to bear his weight on impact. Also, they must be constructed so that there are no protrusions that could cause him injury. If females (or other animals) are present, the jack may run back and forth along the fence and catch his head on anything that is protruding. Hot wires along the inside of a weaker fence will often serve this purpose. However, a hot wire used alone is not sufficient. If your jack becomes frightened, he could run through an electric wire before he even knows that it is there. Giving him a clean, comfortable area where his limits are clearly defined will help him to be a calmer and more manageable animal.

Always make sure your jack’s pen is cleaned daily and that he has free access to clean water, a trace mineral salt block and good grass hay. If he gains too much weight with free choice grass hay, then simply limit his intake to two flakes at each feeding in the morning and evening. He can have a limited amount of oats during one feeding a day (preferably in the evenings), mixed with an appropriate vitamin supplement such as Sho Glo, and one ounce of Mazola corn oil (I suggest this particular brand—other brands of corn oils are not the same) for management of his coat, his feet and his digestive tract regularity. During feeding times, you should check him from top to bottom for any new changes to his body like cuts, bruises, lameness, etc. This is also a good way to reinforce his acceptance of being handled all over and to solidify your relationship with him. This consistent management practice paves the way for good manners in the jack, because he then knows with no uncertainty that you are a true friend and really do care about his well-being.

Many people opt to keep jacks in solitude, but this is not really good for them. Being a natural herd animal, they need social interaction. When they don’t have company nearby, jacks can become depressed (donkeys have actually been known to die from depression—they can stop eating and simply give up). To remedy this, jacks can be pastured or penned next to other animals, as long as the fencing is adequate between them. Of course, you also need to take into consideration the personality types of the animals involved, as well as being careful to make sure they are compatible. This can fulfill their need for companionship and keep them happy in confinement. As long as there are no cycling horse or donkey females around, jacks can be pastured next to mules of both genders. I had my own jack, Little Jack Horner, penned next to our teaser stallion for many years and they actually liked each other! We never had any trouble with them at all.

Many people opt to keep jacks in solitude, but this is not really good for them. Being a natural herd animal, they need social interaction. When they don’t have company nearby, jacks can become depressed (donkeys have actually been known to die from depression—they can stop eating and simply give up). To remedy this, jacks can be pastured or penned next to other animals, as long as the fencing is adequate between them. Of course, you also need to take into consideration the personality types of the animals involved, as well as being careful to make sure they are compatible. This can fulfill their need for companionship and keep them happy in confinement. As long as there are no cycling horse or donkey females around, jacks can be pastured next to mules of both genders. I had my own jack, Little Jack Horner, penned next to our teaser stallion for many years and they actually liked each other! We never had any trouble with them at all.

You can spend more time with your jack by using him for more than just breeding. Animals, like people, always do better when they have a regular job to do that affords them some purpose in life beyond propagation. Some sort of job will give your jack an alternative purpose, which can help to diffuse his obsession with the female. It will also attend to the strength of his core muscles that surround the skeletal system and vital organs and teach him self-discipline. And it affords more time for you to develop your relationship with him, have fun together and to deepen the bond between you, which helps the jack to develop a healthy mental attitude. There are many jack owners who use their jacks for riding and driving, as well as for breeding. This is an excellent and actually the best plan, but if you lack the time or inclination to use your jack this way and wish to use him exclusively for breeding, you should still take some time—at least two or three days a week—to work on halter training and groundwork, such as ground driving, for manageability. Teach your jack to walk, trot, whoa and stand still on the lead. During these sessions, keep a positive and relaxed attitude, with more emphasis on your rapport with him than on his performance. Be his friend so he has something to look forward to besides females and breeding, and he will have a much better attitude overall.

When he is flawless with his leading training, you can get him used to the bridle and a surcingle or lightweight saddle, and then move on to ground driving. Lunging is not as important, since most donkeys do not like to lunge. I suppose they don’t see much purpose in going around in a circle more than once to come back to the same place over and over again. Taking the time to properly train your donkey jack at halter and in the drivelines will enhance his obedience, and will make him more comfortable and relaxed. During the breeding process, it can even speed up his readiness.

When he is flawless with his leading training, you can get him used to the bridle and a surcingle or lightweight saddle, and then move on to ground driving. Lunging is not as important, since most donkeys do not like to lunge. I suppose they don’t see much purpose in going around in a circle more than once to come back to the same place over and over again. Taking the time to properly train your donkey jack at halter and in the drivelines will enhance his obedience, and will make him more comfortable and relaxed. During the breeding process, it can even speed up his readiness.

When using your jack for breeding, develop a routine that he can count on every time. When you go to the stall or pen to catch the jack, wait for him to come to you at the gate or stall door, and then reward him with oats when he comes to you. Then put on the halter, ask him to take one step backwards, and then reward him again (which is very important to prevent him from running over you and barging through the gate  or out the door). If you are going to breed him, the mare should first be prepared. Next, once you are both out the door, ask him to whoa and square up all four feet. Then you can lead him to the breeding area, where you can then tie him to the hitch rail a little ways away from the waiting mare. By being consistent in your manner of going from the stall to the breeding area, the jack will learn not to be pushy and aggressive toward you.

or out the door). If you are going to breed him, the mare should first be prepared. Next, once you are both out the door, ask him to whoa and square up all four feet. Then you can lead him to the breeding area, where you can then tie him to the hitch rail a little ways away from the waiting mare. By being consistent in your manner of going from the stall to the breeding area, the jack will learn not to be pushy and aggressive toward you.

When in the breeding area, your jack must be taught patience and obedience. If the mare is left to stand just out of reach until he is ready to breed, he may consider this a tease and may become anxious and unruly. To clarify your intentions to him, you can take the cloth you used to clean the mare and place it over the hitch rail near your jack’s nose. This way, he can get a good, strong scent of the mare, which will more quickly ready him for breeding and substantially decrease his anxiety time. If he is an indifferent jack, this can actually increase his interest in the female and, in turn, shorten the actual breeding process time. The fact that you brought him the scent allows the jack to believe that it is your decision when to breed and not his and that he must remain obedient. Let him cover the mare only when he is fully ready and make him walk to her in a gentlemanly fashion. If he becomes too aggressive and starts to drag you just return him to his place on the hitch rail, hold him there for a minute, reward him when he stands still and then re-approach the mare.

Just to be on the safe side with your jack while breeding, use either a muzzle or a dropped noseband (snugly fit low on his nose)—this will prevent biting injuries to you or to the mare. When he is finished, make him stand quietly behind the mare while you rinse him off. Allow him that last sniff to the mare’s behind, and then take him back to his stall (or pen), ask him to stand still while you remove the halter and then let him go. That last sniff appears to be an assertion of his act and of his manhood. If you try to lead him away before he sniffs, he might not come with you and he might become even more aggressive toward the mare. Remember to do things with your jack in a routine way, and always with safety in mind—this will allow him to relax and use the manners he has learned. NOTE: Women who are menstruating should never handle jacks or stallions during that particular time, since the scent can trigger aggressive and dangerous behaviors in these animals.

Just to be on the safe side with your jack while breeding, use either a muzzle or a dropped noseband (snugly fit low on his nose)—this will prevent biting injuries to you or to the mare. When he is finished, make him stand quietly behind the mare while you rinse him off. Allow him that last sniff to the mare’s behind, and then take him back to his stall (or pen), ask him to stand still while you remove the halter and then let him go. That last sniff appears to be an assertion of his act and of his manhood. If you try to lead him away before he sniffs, he might not come with you and he might become even more aggressive toward the mare. Remember to do things with your jack in a routine way, and always with safety in mind—this will allow him to relax and use the manners he has learned. NOTE: Women who are menstruating should never handle jacks or stallions during that particular time, since the scent can trigger aggressive and dangerous behaviors in these animals.

When you are around a jack, you must always be alert and know what he is doing at all times. A jack can be the most adorable, loveable, obedient guy in the world, but you must realize that his natural instincts can arise at any time and, although he may not do it intentionally, he can severely hurt you just the same. And when observing a jack from the other side of the fence, always remember that he can come over the top of that fence, teeth bared, so don’t ever turn your back to him or become complacent around him!

Lastly, when putting on or taking off any of his headgear, watch your fingers—when a jack knows the bit is coming, he often opens his jaws to meet it (with anticipation of the bit on a bridle), and your fingers can easily get in the way. Rather than a standard lead rope, it is advisable to use a lead shank with stallions and jacks for the best control. However, I discourage running the chain of a lead shank either through the mouth or over the nose. The correct position for a lead shank is under the jaw. Run the end of the chain through the ring on the near side of the halter noseband, then under the jaw, then through the ring on the opposite side of the noseband, and then clip it to the ring at the throatlatch on the right side of his face. This gives you enough leverage to control him without the halter twisting on his face. If you have spent  plenty of time and done your homework during his leading lessons, your jack will learn to be obedient on the lead shank, even during breeding.

plenty of time and done your homework during his leading lessons, your jack will learn to be obedient on the lead shank, even during breeding.

Retired jacks still need regular attention and proper maintenance to stay healthy into their senior years. Donkeys that do not receive good core muscle maintenance throughout their lives will often begin to sag drastically in the spine as they age. Their gait then becomes stilted, because their balance and strength are severely compromised. They can no longer track properly while moving or square up correctly when at rest. This can lead to irregular calcification in the joints, depression because they don’t feel well and premature health problems. On the other hand, the jack who has had a consistent and healthy management and training routine will enjoy longevity. If you keep these basic management and safety factors in mind, you and your jack can have a long, happy and mutually rewarding relationship!

To learn more about Meredith Hodges and her comprehensive all-breed equine training program, visit LuckyThreeRanch.com, MEREDITH HODGES PUBLIC FIGURE Facebook page, or call 1-800-816-7566. Check out her children’s website at JasperTheMule.com. Also, find Meredith on Pinterest, Instagram, MeWe, YouTube and Twitter.

Covered in TRAINING MULES & DONKEY: A LOGICAL APPROACH TO TRAINING, TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE, VIDEOS #9 & #10 and A GUIDE TO RAISING & SHOWING MULES at www.luckythreeranchstore.com.

© 2013, 2016, 2024 Lucky Three Ranch, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

It’s hard to put your finger on it, but there’s just something a little more special about Vicki. She is way above average when it comes to mules and she definitely commandsyour attention. She embodies the spirit of free expression and an almost eerie reincarnation of a perfect dream…with long ears! Could this “presence” be something genetic, passed down through the ages of Trakehner (and possibly Arabian) breeding? It would seem so.

It’s hard to put your finger on it, but there’s just something a little more special about Vicki. She is way above average when it comes to mules and she definitely commandsyour attention. She embodies the spirit of free expression and an almost eerie reincarnation of a perfect dream…with long ears! Could this “presence” be something genetic, passed down through the ages of Trakehner (and possibly Arabian) breeding? It would seem so.

By Meredith Hodges

By Meredith Hodges jack has a roomy area, free of refuse and debris, and adequately fenced. The fences should be high enough to discourage his leaning over the top and strong enough to bear his weight on impact. Also, they must be constructed so that there are no protrusions that could cause him injury. If females (or other animals) are present, the jack may run back and forth along the fence and catch his head on anything that is protruding. Hot wires along the inside of a weaker fence will often serve this purpose. However, a hot wire used alone is not sufficient. If your jack becomes frightened, he could run through an electric wire before he even knows that it is there. Giving him a clean, comfortable area where his limits are clearly defined will help him to be a calmer and more manageable animal.

jack has a roomy area, free of refuse and debris, and adequately fenced. The fences should be high enough to discourage his leaning over the top and strong enough to bear his weight on impact. Also, they must be constructed so that there are no protrusions that could cause him injury. If females (or other animals) are present, the jack may run back and forth along the fence and catch his head on anything that is protruding. Hot wires along the inside of a weaker fence will often serve this purpose. However, a hot wire used alone is not sufficient. If your jack becomes frightened, he could run through an electric wire before he even knows that it is there. Giving him a clean, comfortable area where his limits are clearly defined will help him to be a calmer and more manageable animal. Many people opt to keep jacks in solitude, but this is not really good for them. Being a natural herd animal, they need social interaction. When they don’t have company nearby, jacks can become depressed (donkeys have actually been known to die from depression—they can stop eating and simply give up). To remedy this, jacks can be pastured or penned next to other animals, as long as the fencing is adequate between them. Of course, you also need to take into consideration the personality types of the animals involved, as well as being careful to make sure they are compatible. This can fulfill their need for companionship and keep them happy in confinement. As long as there are no cycling horse or donkey females around, jacks can be pastured next to mules of both genders. I had my own jack, Little Jack Horner, penned next to our teaser stallion for many years and they actually liked each other! We never had any trouble with them at all.

Many people opt to keep jacks in solitude, but this is not really good for them. Being a natural herd animal, they need social interaction. When they don’t have company nearby, jacks can become depressed (donkeys have actually been known to die from depression—they can stop eating and simply give up). To remedy this, jacks can be pastured or penned next to other animals, as long as the fencing is adequate between them. Of course, you also need to take into consideration the personality types of the animals involved, as well as being careful to make sure they are compatible. This can fulfill their need for companionship and keep them happy in confinement. As long as there are no cycling horse or donkey females around, jacks can be pastured next to mules of both genders. I had my own jack, Little Jack Horner, penned next to our teaser stallion for many years and they actually liked each other! We never had any trouble with them at all. When he is flawless with his leading training, you can get him used to the bridle and a surcingle or lightweight saddle, and then move on to ground driving. Lunging is not as important, since most donkeys do not like to lunge. I suppose they don’t see much purpose in going around in a circle more than once to come back to the same place over and over again. Taking the time to properly train your donkey jack at halter and in the drivelines will enhance his obedience, and will make him more comfortable and relaxed. During the breeding process, it can even speed up his readiness.

When he is flawless with his leading training, you can get him used to the bridle and a surcingle or lightweight saddle, and then move on to ground driving. Lunging is not as important, since most donkeys do not like to lunge. I suppose they don’t see much purpose in going around in a circle more than once to come back to the same place over and over again. Taking the time to properly train your donkey jack at halter and in the drivelines will enhance his obedience, and will make him more comfortable and relaxed. During the breeding process, it can even speed up his readiness. or out the door). If you are going to breed him, the mare should first be prepared. Next, once you are both out the door, ask him to whoa and square up all four feet. Then you can lead him to the breeding area, where you can then tie him to the hitch rail a little ways away from the waiting mare. By being consistent in your manner of going from the stall to the breeding area, the jack will learn not to be pushy and aggressive toward you.

or out the door). If you are going to breed him, the mare should first be prepared. Next, once you are both out the door, ask him to whoa and square up all four feet. Then you can lead him to the breeding area, where you can then tie him to the hitch rail a little ways away from the waiting mare. By being consistent in your manner of going from the stall to the breeding area, the jack will learn not to be pushy and aggressive toward you. Just to be on the safe side with your jack while breeding, use either a muzzle or a dropped noseband (snugly fit low on his nose)—this will prevent biting injuries to you or to the mare. When he is finished, make him stand quietly behind the mare while you rinse him off. Allow him that last sniff to the mare’s behind, and then take him back to his stall (or pen), ask him to stand still while you remove the halter and then let him go. That last sniff appears to be an assertion of his act and of his manhood. If you try to lead him away before he sniffs, he might not come with you and he might become even more aggressive toward the mare. Remember to do things with your jack in a routine way, and always with safety in mind—this will allow him to relax and use the manners he has learned. NOTE: Women who are menstruating should never handle jacks or stallions during that particular time, since the scent can trigger aggressive and dangerous behaviors in these animals.

Just to be on the safe side with your jack while breeding, use either a muzzle or a dropped noseband (snugly fit low on his nose)—this will prevent biting injuries to you or to the mare. When he is finished, make him stand quietly behind the mare while you rinse him off. Allow him that last sniff to the mare’s behind, and then take him back to his stall (or pen), ask him to stand still while you remove the halter and then let him go. That last sniff appears to be an assertion of his act and of his manhood. If you try to lead him away before he sniffs, he might not come with you and he might become even more aggressive toward the mare. Remember to do things with your jack in a routine way, and always with safety in mind—this will allow him to relax and use the manners he has learned. NOTE: Women who are menstruating should never handle jacks or stallions during that particular time, since the scent can trigger aggressive and dangerous behaviors in these animals. plenty of time and done your homework during his leading lessons, your jack will learn to be obedient on the lead shank, even during breeding.

plenty of time and done your homework during his leading lessons, your jack will learn to be obedient on the lead shank, even during breeding.

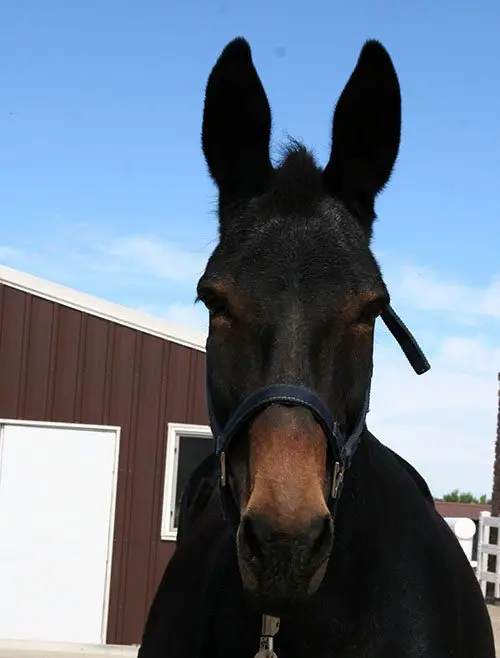

The ideal mule should have a head that is slightly longer than that of a horse, but proportionate to the size of the mule’s body. The features should be prominent and give an overall pleasant appearance. The ears should have length and be nicely shaped, and the eyes should be large, soft and kind, reflecting the mule’s health and intelligence. The forehead should be broad, tapering to a small and delicate muzzle, with a shallow mouth and well-aligned teeth, and the nostrils should be wide to allow for adequate respiration while working. Both the mare and the jack are responsible for the shaping of these characteristics, but the jack has primary responsibility where the length of the ear and the mass of bone are concerned. A jack with a longer ear will, more often than not, throw a longer ear to the mule, while the shape of the ear is determined primarily by the mare. The attractive or unattractive head of the jack can emerge in the resulting mule, so be sure to carefully consider the head on the jack to be used for breeding to produce an attractive head on your mule offspring. Standard-sized jacks and Large Standard jacks most often have a more refined head, while the head of a Mammoth jack may be less refined and possess

The ideal mule should have a head that is slightly longer than that of a horse, but proportionate to the size of the mule’s body. The features should be prominent and give an overall pleasant appearance. The ears should have length and be nicely shaped, and the eyes should be large, soft and kind, reflecting the mule’s health and intelligence. The forehead should be broad, tapering to a small and delicate muzzle, with a shallow mouth and well-aligned teeth, and the nostrils should be wide to allow for adequate respiration while working. Both the mare and the jack are responsible for the shaping of these characteristics, but the jack has primary responsibility where the length of the ear and the mass of bone are concerned. A jack with a longer ear will, more often than not, throw a longer ear to the mule, while the shape of the ear is determined primarily by the mare. The attractive or unattractive head of the jack can emerge in the resulting mule, so be sure to carefully consider the head on the jack to be used for breeding to produce an attractive head on your mule offspring. Standard-sized jacks and Large Standard jacks most often have a more refined head, while the head of a Mammoth jack may be less refined and possess  thicker bone, particularly around the eyes and jaw line. In the case of saddle mule production, massive bone on an otherwise attractive head can be very unattractive, so using the smaller jacks would be better for a more refined look in your saddle mule (which is also true for the rest of the mule’s body).

thicker bone, particularly around the eyes and jaw line. In the case of saddle mule production, massive bone on an otherwise attractive head can be very unattractive, so using the smaller jacks would be better for a more refined look in your saddle mule (which is also true for the rest of the mule’s body).

The shoulders of the mule should be at a nearly 45-degree angle, with a broad collar surface. Most mares will have this angle, but donkeys have a tendency toward short, steep shoulders, so, to insure that the mule has good shoulders and hips, consider a jack with good length and a lower angle through the shoulders and hips.

The shoulders of the mule should be at a nearly 45-degree angle, with a broad collar surface. Most mares will have this angle, but donkeys have a tendency toward short, steep shoulders, so, to insure that the mule has good shoulders and hips, consider a jack with good length and a lower angle through the shoulders and hips. The chest of the mule should be deep and prominent, broad and well developed (it should resemble a turkey’s breast), with little or no line of separation (as is seen in a horse’s chest). Since jacks are generally narrower through the chest than are mares, the mare chosen for breeding should exhibit much width and depth through the chest to compensate for the lack of it in the jack.

The chest of the mule should be deep and prominent, broad and well developed (it should resemble a turkey’s breast), with little or no line of separation (as is seen in a horse’s chest). Since jacks are generally narrower through the chest than are mares, the mare chosen for breeding should exhibit much width and depth through the chest to compensate for the lack of it in the jack. If a stockier mule is desired (as in the case of breeding for pack or draft mules), a stockier mare bred to a Mammoth jack will produce the desired thickness of bone in the legs of the mule. If a more refined Thoroughbred appearance is desired, the mare should be bred to a Standard or Large Standard jack in order to reduce the mass of the bone in the legs of the mule and retain refinement throughout the body. This does not affect the height of the mule, as the mare is primarily responsible for the mule’s height, while the jack is primarily responsible for the mule’s bone thickness. The forearm and stifle in the mule should be well developed and thickly covered with smooth muscle that tapers to the knee and hock in regular, well-defined lines. Again, these muscles should be thick and smooth, but not bulging, as in horses. The mare will compensate for the limited bulk muscling in the donkey jack, and the jack will contribute and maintain the smoothness of that additional bulk muscle in the mule.

If a stockier mule is desired (as in the case of breeding for pack or draft mules), a stockier mare bred to a Mammoth jack will produce the desired thickness of bone in the legs of the mule. If a more refined Thoroughbred appearance is desired, the mare should be bred to a Standard or Large Standard jack in order to reduce the mass of the bone in the legs of the mule and retain refinement throughout the body. This does not affect the height of the mule, as the mare is primarily responsible for the mule’s height, while the jack is primarily responsible for the mule’s bone thickness. The forearm and stifle in the mule should be well developed and thickly covered with smooth muscle that tapers to the knee and hock in regular, well-defined lines. Again, these muscles should be thick and smooth, but not bulging, as in horses. The mare will compensate for the limited bulk muscling in the donkey jack, and the jack will contribute and maintain the smoothness of that additional bulk muscle in the mule. The coat and hair of the mule should be soft and shiny, covering pliable skin. The coat should be soft to the touch, denoting good skin health. Length and thickness of the coat are contributed by both jack and mare. Since donkeys have a typically thick coat of hair, a mare with a thinner coat will balance this thick hair coat in the mule, making him look sleeker and more horse-like than his donkey sire.

The coat and hair of the mule should be soft and shiny, covering pliable skin. The coat should be soft to the touch, denoting good skin health. Length and thickness of the coat are contributed by both jack and mare. Since donkeys have a typically thick coat of hair, a mare with a thinner coat will balance this thick hair coat in the mule, making him look sleeker and more horse-like than his donkey sire.