From the SWISS BULLETIN: Evidence of mules in ancient times, Part 2

We hope you enjoy Part 2 of the translated historical Longears article written by Elke Stadler, originally printed in German in the SWISS BULLETIN that comes to us from Switzerland. More articles to follow!

By Elke Stadler

Further evidence of mules in ancient times is shown by finds from various archaeological excavations. The identification of hybrids is more and more illuminated by archaeological research. The finds of mule bones on civil and military sites are scattered throughout Europe.

In Pompeii

Pompeii was an ancient city located in the modern commune of Pompei near Naples in the Campania region of Italy. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pompeii

In the stable of the house of “Casa Amanti” the remains of equine skeletons were found, five in total, including four donkeys between 4 and 9 years old and one male mule between 8 and 9 years old. The equines were probably used as pack animals for the transport of pastries. An analysis of the food remains in the stable was also taken.

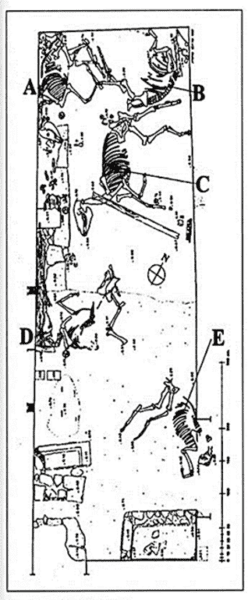

Left: Plan of a horse stable in Pompei, Anthopozoologica 31,2000, pp. 119-123.

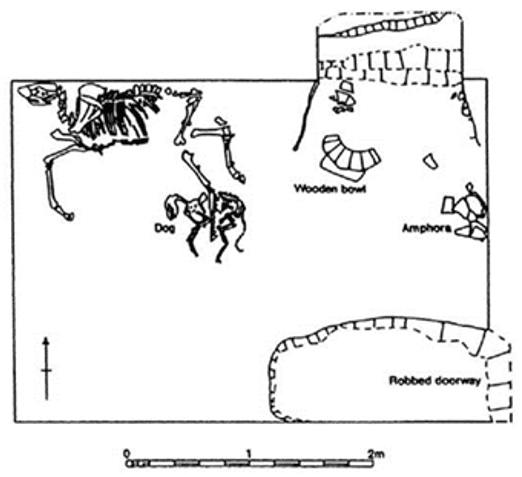

Right: Pompeii, Casa Amanti, houses 6 and 7, Insula 12, region IX, Genovese A, Cocca T.

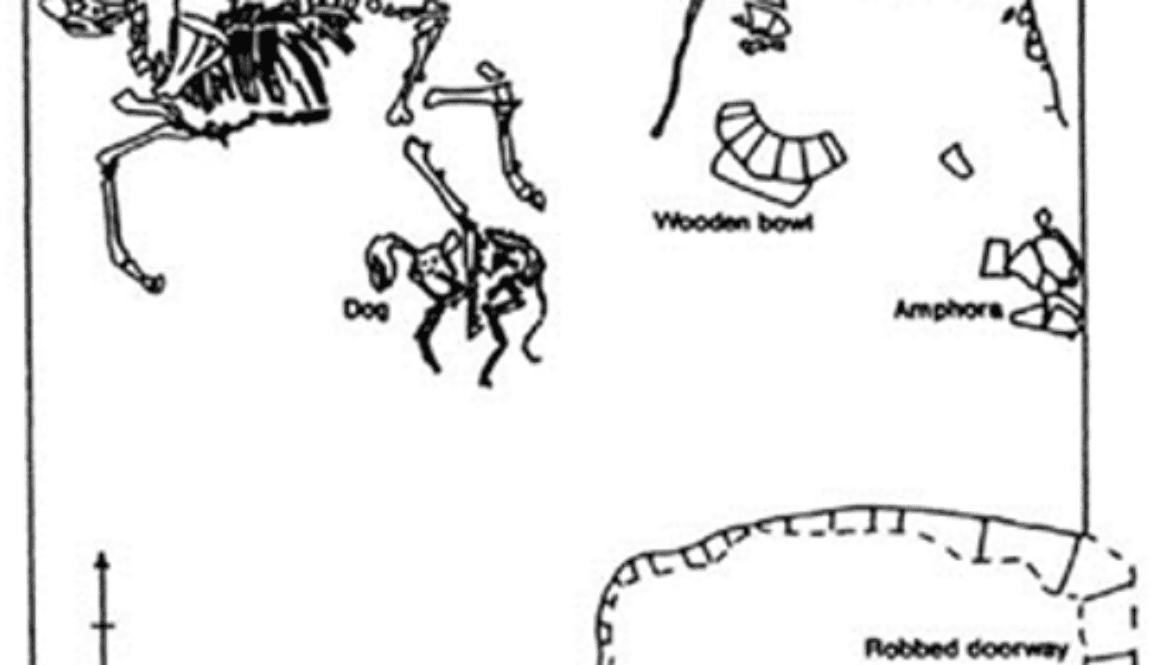

Pompeii, Insula 9, house 12, room 4, region I, (casa amarantus)

(Berry J., The conditions of domestic life in pompii in AD 79: A case study of houses 11 and 12, insula 9, region I, Papers of the British School at Rome)

In the stable on this area, probably originally a “Kubikulum” (side room), the skeletons of a mule and a dog were found. On the northern wall, remains of wood can be seen, which indicate a feeding rack. The palynological examination of the plant remains showed a variety of grasses and weeds as well as cereals, olives and nuts, indicating forage, litter and dung. Two fortified iron rings near the mule’s head suggest that it was tied up at the time of death.

The large number of amphorae in the “Impluvium” (water collection basin) of the nearby atrium (Roman dwelling house), as well as the remains of a broken amphora in the stable, indicate that the mule was intended to transport amphorae to the city. The remains of a dilapidated “Caupona” (bar, sales room) in the adjacent Insula 11 indicate commercial activity. An inscription on the western front (AMARANTUS POMPEIANUS ROG (AT) and three painted inscriptions, one on the neck (EX POMPEI AMARANTI) and two on the belly of several amphorae found in the building, indicate that Amarantus was a wine merchant, which required the keeping of a mule to transport the amphorae.

Great Britain, London

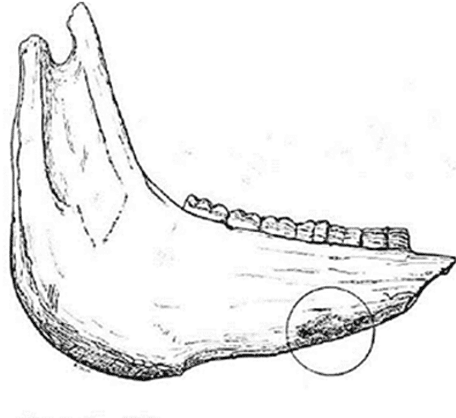

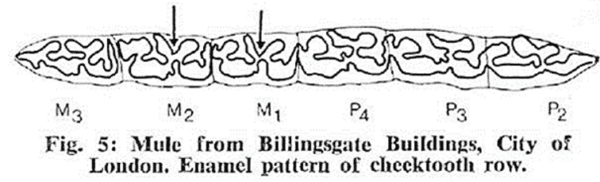

The mule jaw was found in a landfill. It dates from the Roman period (period II, phase 3) around 125-160 A.D. Age at death of the animal: more than 5 years, perhaps between 11 and 14 years.

The age determination is inaccurate, as the jaw is broken at the level of the incisors. The age can only be determined more accurately on the basis of the wear and tear of the incisors. It was also not possible to determine the sex because of the missing canines, the sex index. They are more developed in males than in females. The pronounced wear in an area of the jawbone (circle) is probably the result of the damaging pressure from a halter or muzzle.

Examination of the molar profile of the jaw made it possible to determine the London jaw more reliably than mule jaws. It has a very accentuated “V” shape of the lateral cavities of the first molars (cheek teeth). The comparison with the lower jaw of another mule (Dangstetten) shows a strong similarity.

According to Armitage P, Chapman C, Roman Mules, The London Archaeologist, 3/13,1979, S. 339-359)

Kalkriese, Niedersachsen, Germany

The finding region Kalkriese is an area in northwest of Germany, where large quantities of Roman archaeological finds were made. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kalkriese

Archaeologists have identified the bones of eight horses and about thirty mules on the site of the Battle of Kalkriese, which took place in 9 A.D., including two skeletons in good condition at the trenches dug by the Germans to capture the Roman vanguard. The first mule was found in the trench, its bones (head, neck and shoulders) and its harnesses are in adequate position. The animal was therefore not completely exposed to natural decay (which explains the good osteological and anatomical preservation conditions).

The mule had an iron bridle and harness with metal elements and stones, and a bronze bell with iron clapper. The inside of the bell was stuffed with oat straw wrapped around the clapper so that the bells were not heard in enemy territory. The growth of the roots on the stems indicated late summer – early autumn, which made it possible to determine the date of the ambush around September.

In 1999 the fragmentary remains of a second 4-year-old mule were found. It carried a smaller bronze bell and an iron bridle. The animal died of a broken neck, probably while trying to climb the German wall in the general panic of the fight.

According to: Rost A, Wilbers -Rost S; Waffen auf dem Schlachtfeld von Kalkriese, Gladius XXX; 2010, pp. 117-135 and Harnecker J, Franzius G, Kalkriese 4th Catalogue of Roman Finds from the Oberesch. Die Schnitte 1 bis 22; Römisch-Germanische Forschungen vol. 66. 2008 and Wells P.S., Die Schlacht, die Rom stoppte, Kaiser Augustus, Arminius und das Abschlachten der Legionen im Teutoburger Wald, 2003)

Carnuntum, Austria

It is the most important and most extensively researched ancient excavation site in Austria 28 mi east of Vienna. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carnuntum

Horses and mule bones were discovered in the outer ditch and in pits on the edge of the first ditch of this Roman legionary camp. Four mules could be identified from the remains. The sex could be determined based on the development of the canines on the lower jaws. They were only male animals. Two of them died at the age of 6-7 years, the other two at about 15-17 years. The age is estimated on the basis of the abrasion of the teeth. Since mule teeth are harder than those of horses, the age had been underestimated and had to be reassessed.

The height at the withers was determined in relation to the length of the bones found. It was approximately between not less than 140 cm and maximum 155 cm. Apart from one mule, the other three suffered from diseases of the limbs and/or the spine caused by frequent heavy loading. A pathological change in the spinal column of a mule also indicates this. One shows a pathology (exostosis) on the jaw, which is caused by repeated rubbing of a bit or harness.

According to: Kunst G. K., Archäozoologischer Nachweis für Equidengebrauch, Geschlechtsstruktur und Mortalität in einem neuartigen Hilfskastell (Carnuntum-Petronell, Niederösterreich), Anthropozoologica 31; Ibex J. Mt. Ecol 5.2000

Weissenburg, Bavaria, Germany, Biriciana Roman Fort

The Roman fort at Weissenburg, called Biriciana in ancient times, is a former Roman Ala castellum, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site located near the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biriciana

The Roman fort at Weissenburg, called Biriciana in ancient times, is a former Roman Ala castellum, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site located near the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biriciana

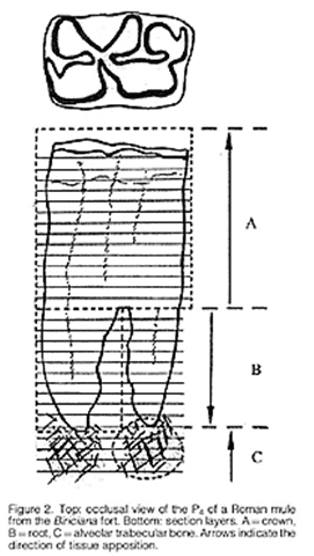

Four skeletal remains of mules were found during an excavation in this Roman camp. The age was determined to be 160 AD after the discovery of eleven coins. They were found in a bag that was left with the mules. The authors raise the question of a possible local breeding or traditional import of mules from Mediterranean countries. When examining the teeth of an 8-year-old mule, it was found that the food in the mule’s environment must have changed until the time of its death. The animal spent part of its life at high altitude, according to the proximity of the camp, probably in the Alps. The investigations show that the animal must have been born and bred in northern Italy. It must have been used for work in the Alps for a while and later on until the end of its life near Fort Weissenburg.

According to Berger T. E., Peters J., Grupe G. Life history of a mule (ca. 160 AD) from the Roman fort Biriciana/Weissenburg (Upper Bavaria), as revealed by serial stable isotope analysis of dental tissue, International Journal of Osteoarchaeology Volume 20, Issue 2, March/April 2010, pp. 158-171.

Further Sources: https://leg8.fr/armee-romaine/mulet-du-ier-siecle-qui-es-tu

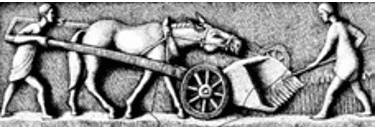

At that time, cattle were the most important draft animals, less for meat production, and milk was also of little importance. Cattle were mainly used in agricultural traction work or heavy transports with wagons. Oxen were indispensable for long-distance transport. No person, no matter how much they preferred mules, camels or even elephants, could do without cattle. They were much less demanding of food and care than the sensitive horse, which was expensive to keep. The mule took a special position because of its outstanding qualities. Horses are hardly mentioned in the old writings as draft animals for heavier loads. Mostly, they were used for light wagons. Horses were the mount of the high-ranking men, both civilian and military, and also served as a pack animal.

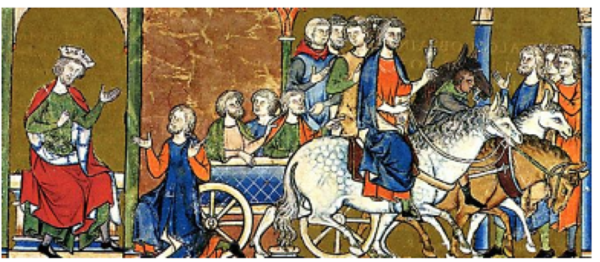

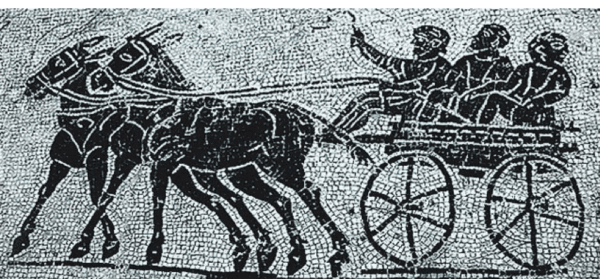

At that time, cattle were the most important draft animals, less for meat production, and milk was also of little importance. Cattle were mainly used in agricultural traction work or heavy transports with wagons. Oxen were indispensable for long-distance transport. No person, no matter how much they preferred mules, camels or even elephants, could do without cattle. They were much less demanding of food and care than the sensitive horse, which was expensive to keep. The mule took a special position because of its outstanding qualities. Horses are hardly mentioned in the old writings as draft animals for heavier loads. Mostly, they were used for light wagons. Horses were the mount of the high-ranking men, both civilian and military, and also served as a pack animal. Female animals were used primarily for pulling wagons because of their agility, while male mules were used to carry loads. Various documents show this division for different purposes. Emperor Serverus Alexander gave his provincial leaders six female mules, two male mules and two horses. It is obvious that the female mules were intended for specific use as draft animals, the male mules as pack animals and the horses for mounts. The female mules were reserved for pulling which is evident from the fact that they were normally traded as a team. If one had a flaw, the seller had to take back both animals. It was especially popular when all the animals in front of a cart had the same color. The veterinarians gave recipes for dyeing the hair of the draft animals when it was not appropriate. To make white hair black, three ‘scripula’ (Roman unit of weight) cobbler’s blacks, four ‘scripula’ oleander’s juice and some goat fat are mixed, crushed and then applied. To make black hair white, a pound of wild cucumber root and twelve ‘scripula’ soda are crushed into powder, a cup of honey added, and then applied.

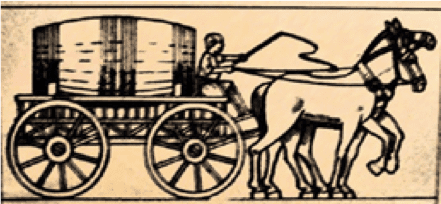

Female animals were used primarily for pulling wagons because of their agility, while male mules were used to carry loads. Various documents show this division for different purposes. Emperor Serverus Alexander gave his provincial leaders six female mules, two male mules and two horses. It is obvious that the female mules were intended for specific use as draft animals, the male mules as pack animals and the horses for mounts. The female mules were reserved for pulling which is evident from the fact that they were normally traded as a team. If one had a flaw, the seller had to take back both animals. It was especially popular when all the animals in front of a cart had the same color. The veterinarians gave recipes for dyeing the hair of the draft animals when it was not appropriate. To make white hair black, three ‘scripula’ (Roman unit of weight) cobbler’s blacks, four ‘scripula’ oleander’s juice and some goat fat are mixed, crushed and then applied. To make black hair white, a pound of wild cucumber root and twelve ‘scripula’ soda are crushed into powder, a cup of honey added, and then applied. Most mules were not used as valuable draft animals in private passenger transport, but in public transport by rental car companies or by cargo. The provisions of Codex Theodosianus (late antiquity collection of laws) the ‘cursus publicus’, can give an approximate impression. Two car types are mentioned, the four-wheeled ‘raeda’ and the two-wheeled ‘birota’. The ‘raeda’ was fitted with eight mules in summer and ten in winter, 1000 pounds could be carried. When used by people, this corresponded to seven to eight passengers. For the ‘birota’ on the other hand, three mules and a maximum load of 200 pounds were prescribed, for a person’s use, this was two passengers.

Most mules were not used as valuable draft animals in private passenger transport, but in public transport by rental car companies or by cargo. The provisions of Codex Theodosianus (late antiquity collection of laws) the ‘cursus publicus’, can give an approximate impression. Two car types are mentioned, the four-wheeled ‘raeda’ and the two-wheeled ‘birota’. The ‘raeda’ was fitted with eight mules in summer and ten in winter, 1000 pounds could be carried. When used by people, this corresponded to seven to eight passengers. For the ‘birota’ on the other hand, three mules and a maximum load of 200 pounds were prescribed, for a person’s use, this was two passengers.  The journey with such public transport was accompanied by wild screams, whip cracks from a drunken coachman and clouds of dust, reports a letter writer named Eustathios: A trip with mules that were boisterous by doing nothing and feeding too much he avoided – and prefered to walk.

The journey with such public transport was accompanied by wild screams, whip cracks from a drunken coachman and clouds of dust, reports a letter writer named Eustathios: A trip with mules that were boisterous by doing nothing and feeding too much he avoided – and prefered to walk.

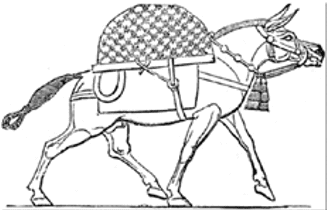

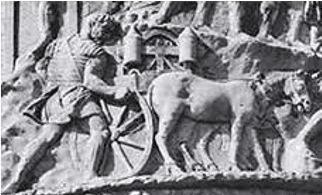

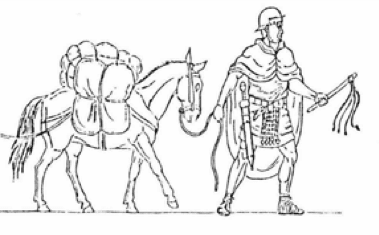

Male mules were used to carry less extensive loads in cities and agriculture because of their greater strength. The typical work was the transport of pole wood for plantations. Traders kept their mules directly in their shops. There is a case described in the Digests (scripts of ancient legal scholars) where a horse was led into a shop and was sniffing at the mule there. It kicked and broke the back of the horse’s leader. In the troop, each centurion had one such pack mule, which had to carry the heavier parts of the equipment on the marches.

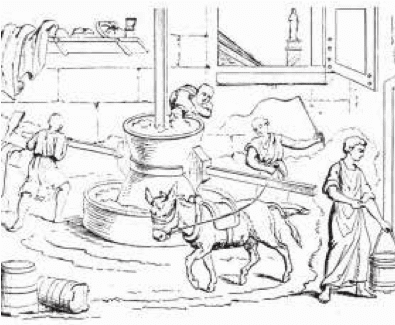

Male mules were used to carry less extensive loads in cities and agriculture because of their greater strength. The typical work was the transport of pole wood for plantations. Traders kept their mules directly in their shops. There is a case described in the Digests (scripts of ancient legal scholars) where a horse was led into a shop and was sniffing at the mule there. It kicked and broke the back of the horse’s leader. In the troop, each centurion had one such pack mule, which had to carry the heavier parts of the equipment on the marches. Mules were often used, as donkeys and horses were, to drive mills when they were no longer usable for other services. They were harnessed with a hard grass rope in front of the mill beam, the head was usually masked. They trotted in a furrow, always pushed by blows in the circle around. The bad condition of the animals corresponded to the gruelling work. In the “Methamorphoses”, Apuleius describes that the necks were swollen of wound rot, the nostrils were flaccid and dilated from coughing and dusty air. The body was disfigured by the constant blows and mange, the feet clumped by traveling permanently in a circle. These sufferings are also reflected in the veterinary writings, but the mill animals were certainly no longer treated.

Mules were often used, as donkeys and horses were, to drive mills when they were no longer usable for other services. They were harnessed with a hard grass rope in front of the mill beam, the head was usually masked. They trotted in a furrow, always pushed by blows in the circle around. The bad condition of the animals corresponded to the gruelling work. In the “Methamorphoses”, Apuleius describes that the necks were swollen of wound rot, the nostrils were flaccid and dilated from coughing and dusty air. The body was disfigured by the constant blows and mange, the feet clumped by traveling permanently in a circle. These sufferings are also reflected in the veterinary writings, but the mill animals were certainly no longer treated. The mule was used rarely for riding in Antiquity, it was the simpler mount. Horace (poet) illustrates a simple but also free life in this way: He could bridle a mule at any time and head all the way to Taranto, even if the loins of the animal were rubbed sore by the heavy coat bag and the sides by the weight of the rider. The veterinarians list these specific injuries caused by riding, as well as, by loads being too heavy. The wounds are treated with ointments mixed from salt, wine, oil, raisin wine, pork fat and onions. In more severe cases, blood is taken from the veins of the groin area and mixed with salt, pork fat and oil. This is applied, and if necessary, plastered with ointment. For wounded skin caused by pressures, a dough-like mixture made of fine wheat flour, incense dust, egg yolk and vinegar is applied to the sore spots.

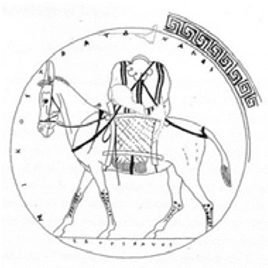

The mule was used rarely for riding in Antiquity, it was the simpler mount. Horace (poet) illustrates a simple but also free life in this way: He could bridle a mule at any time and head all the way to Taranto, even if the loins of the animal were rubbed sore by the heavy coat bag and the sides by the weight of the rider. The veterinarians list these specific injuries caused by riding, as well as, by loads being too heavy. The wounds are treated with ointments mixed from salt, wine, oil, raisin wine, pork fat and onions. In more severe cases, blood is taken from the veins of the groin area and mixed with salt, pork fat and oil. This is applied, and if necessary, plastered with ointment. For wounded skin caused by pressures, a dough-like mixture made of fine wheat flour, incense dust, egg yolk and vinegar is applied to the sore spots. Although mules were regarded by the church leaders as originating from an unnatural connection, and thus had a bad reputation, the mule nevertheless experienced a great appreciation in the early Middle Ages. Since Spanish mules are a noble gift, Emperor Charlemagne sent them to Caliph Harun Rashid. Mules and their Saracen guardians were bestowed by Robert Guiscard (Norman leader) to the Abbot of Montecassino. The mule is often mentioned as a mount of clergy. Gallus, for example, uses a mule for his journey to the Swabian ducal court. Also, for the journey of Goar (Priest, later holy spoken) to the royal court, a mule or a donkey is intended. Bishop Gregory of Tours, mentions mules among the farm animals of the monastery St. Martin, which were obviously riding animals. Because of the clergy’s preference for mules, the devil – as Notker (poet and scholar) tells us he turns into a mule to tempt the bishop to buy him, seduces him and kills him on the way out. A degree accordingly acts against the excessive dealing of clergy with mules. Of course, mules were often used as pack animals in the early Middle Ages, just like horses. Already Isidor from Sevilla (Archbishop) speaks about the ‘mulus sagmaria’ (Latin: pack mule) beside the ‘caballus sagmarius’ (packhorse). Some of the mules and horses with which the Irish bishop Marcus returned from his trip to Rome must have been pack animals as books, gold objects and robes are mentioned as transported goods. In the Vita Hludovici (anonymous biography of Louis the Pious) mules are also mentioned beside horses, working a mission as they transported ship parts through the woods. Mules are also considered a pack animal in custom regulations.

Although mules were regarded by the church leaders as originating from an unnatural connection, and thus had a bad reputation, the mule nevertheless experienced a great appreciation in the early Middle Ages. Since Spanish mules are a noble gift, Emperor Charlemagne sent them to Caliph Harun Rashid. Mules and their Saracen guardians were bestowed by Robert Guiscard (Norman leader) to the Abbot of Montecassino. The mule is often mentioned as a mount of clergy. Gallus, for example, uses a mule for his journey to the Swabian ducal court. Also, for the journey of Goar (Priest, later holy spoken) to the royal court, a mule or a donkey is intended. Bishop Gregory of Tours, mentions mules among the farm animals of the monastery St. Martin, which were obviously riding animals. Because of the clergy’s preference for mules, the devil – as Notker (poet and scholar) tells us he turns into a mule to tempt the bishop to buy him, seduces him and kills him on the way out. A degree accordingly acts against the excessive dealing of clergy with mules. Of course, mules were often used as pack animals in the early Middle Ages, just like horses. Already Isidor from Sevilla (Archbishop) speaks about the ‘mulus sagmaria’ (Latin: pack mule) beside the ‘caballus sagmarius’ (packhorse). Some of the mules and horses with which the Irish bishop Marcus returned from his trip to Rome must have been pack animals as books, gold objects and robes are mentioned as transported goods. In the Vita Hludovici (anonymous biography of Louis the Pious) mules are also mentioned beside horses, working a mission as they transported ship parts through the woods. Mules are also considered a pack animal in custom regulations.