LTR Training Tip #6: Feeding Time – Oat Mixture

Meredith gets a lot of letters and emails from people with training questions about their equines. Here, she discusses the best way to incorporate an oats mixture into your equine’s diet.

Meredith gets a lot of letters and emails from people with training questions about their equines. Here, she discusses the best way to incorporate an oats mixture into your equine’s diet.

By Meredith Hodges

It is important to know the differences among rewards, treats, coaxing and bribing in order to correctly employ the reward system of training called Behavior Modification.

It is important to know the differences among rewards, treats, coaxing and bribing in order to correctly employ the reward system of training called Behavior Modification.

Rule Number One: Treats and bribery should never be used during training. However, the appropriate dispensing of rewards and coaxing will produce the correct behaviors.

In order to reward your equine correctly for performing tasks, it is important to know the difference between a reward and a treat, and between coaxing and bribing. Let’s begin with some basic definitions of these terms:

Reward: something desirable given for a completed task

Treat: an unexpected gift given simply because it will be enjoyed

Coax: to gently persuade without dispensing the reward

Bribe: to persuade the animal by indiscriminately dispensing treats

Remember to give your equine a reward only after a specific task you’ve asked for has been performed—or even an assimilation of that task, which means the taking of baby steps toward completing the task. The reward should be given immediately upon completion of the task and then your equine should be allowed time to enjoy his reward before moving on to the next task. If your equine is given a food reward for only good behaviors, he will be more likely to continue to repeat only those behaviors for which he is rewarded and you can begin to “shape” his behavior in a positive way.

Remember to give your equine a reward only after a specific task you’ve asked for has been performed—or even an assimilation of that task, which means the taking of baby steps toward completing the task. The reward should be given immediately upon completion of the task and then your equine should be allowed time to enjoy his reward before moving on to the next task. If your equine is given a food reward for only good behaviors, he will be more likely to continue to repeat only those behaviors for which he is rewarded and you can begin to “shape” his behavior in a positive way.

Treats, on the other hand, are a food that your equine especially likes, which are given randomly and without purpose. Giving random treats during training can result in crossed signals and confusion in your animal. Treats such as peppermints and even “horse treats” are generally an inappropriate food source for equines and when dispensed too freely, have actually been known to cause equine health problems, so forego treats of any kind during the training process.

Coaxing and bribing can seem like the same thing, but they are not. Bribery suggests the actual dispensing of a reward before the task has been completed. Bribery is the indiscriminate dispensing of treats and is not the way to clearly communicate to your equine which is truly a positive behavior and which is not. Rewards and coaxing are often confused with bribery, but rewards are dispensed for a task only when it has been completed, and coaxing using the promise of a reward can often be used to help your equine to stop balking and attempt to perform the task you have requested. Then the reward is given only when he has completed the task.

As an example of coaxing, you can extend a handful of crimped oats to lure your equine closer to an obstacle, but he should not receive the handful of oats until he completes the required task or travels enough distance toward the obstacle to deserve a reward. If your equine just won’t come all the way to an obstacle, even to get a reward, you can modify the task by asking your equine to just come closer to the obstacle and then halt (but without backing up). Then the reward can be dispensed for the partial approach and halt, because these actions still qualify as an assimilation of the bigger task that is to be completed. If he backs away at all, he should not be rewarded and you will have to go back to the beginning of the task and try again.

As an example of coaxing, you can extend a handful of crimped oats to lure your equine closer to an obstacle, but he should not receive the handful of oats until he completes the required task or travels enough distance toward the obstacle to deserve a reward. If your equine just won’t come all the way to an obstacle, even to get a reward, you can modify the task by asking your equine to just come closer to the obstacle and then halt (but without backing up). Then the reward can be dispensed for the partial approach and halt, because these actions still qualify as an assimilation of the bigger task that is to be completed. If he backs away at all, he should not be rewarded and you will have to go back to the beginning of the task and try again.

A kind word or a pat on the head may be enjoyable for your equine, but it doesn’t necessarily insure that the desired behavior will be repeated. However, a food reward insures that desirable behaviors will be repeated, because food is a solid, tangible reward. The food reward will back up the petting, (the petting is something that you probably do all the time anyway). When you visit your equine, you most likely pat him on the nose or head and say hello, but there are no real demands for any particular task being asked of your equine—you and your equine are simply interacting. You’re getting him used to touch, discovering how he likes to be touched and learning about his responses, which is actually part of imprinting.

The problem with carrots, apples and other foods people use for treats is that they’re not something for which the equine will continue to work and are not healthy choices for your animal in large quantities. After a limited amount of time, equines can easily become satiated on most treats. It’s like a kid with a bunch of candy bars. Once they become full they don’t want any more candy and they’ll stop working for the treat. Many foods used as treats, when given too freely, may also cause your animal to become tense or hyperactive. However, it’s been my experience that an equine will continue to work for crimped oats as long as you dole them out. Crimped oats are healthy for the body and they don’t cause an equine to become tense and difficult to handle.

When you’re using rewards, always start with lavish rewards for all new behaviors. This means that, every time you teach something new, you’re going to give lavish rewards for even the slightest assimilation toward the correct behavior. For instance, if your foal is tied to the fence and upon your approach, he quits pulling, it’s time to try to walk away from the fence with him and see if he will follow you. In this first leading lesson, you’ll untie him and ask him to take a step toward you. If he does, lavishly reward that step toward you, wait for him to finish chewing his oats and then ask him to take another step forward and toward you. If he complies and takes another step forward, lavishly reward that step too. During the first lesson, you will be rewarding every single step he takes toward you. Remember to keep the lesson short (about 15 minutes) and ask for only as many steps as he willingly gives you.

Between lessons, let your equine have a day off in order to rest. When you return for the second lesson, tie him to the fence and review with him your last lesson from the very beginning. He should remember the previous lessons and be willing to follow you right away in order to be rewarded. If he seems willing to follow your lead, untie him and ask him to take a step forward just as he did before, but this time, instead of dispensing the food reward when he takes the first step forward, simply say, “Good boy” and ask him for a second step forward before you reward him with the oats. You will now be progressing from one step forward before you reward to two steps forward before you reward.

Between lessons, let your equine have a day off in order to rest. When you return for the second lesson, tie him to the fence and review with him your last lesson from the very beginning. He should remember the previous lessons and be willing to follow you right away in order to be rewarded. If he seems willing to follow your lead, untie him and ask him to take a step forward just as he did before, but this time, instead of dispensing the food reward when he takes the first step forward, simply say, “Good boy” and ask him for a second step forward before you reward him with the oats. You will now be progressing from one step forward before you reward to two steps forward before you reward.

If he won’t take the second step forward, then give the reward for the first step, wait for him to finish chewing and ask again for two steps before rewarding him again. If he complies, you can then reward him every two steps during that lesson and quit after fifteen minutes. Give him another day between lessons and then proceed in the same manner, beginning with a review of the previous lesson, then a reward for the first step, and then for every two steps. During this lesson, you can now ask for three steps, and you can continue asking for three or more steps during this lesson, provided that he takes these steps willingly and then stops obediently on his own to receive his reward. You no longer need to count the steps as long as he is offering more steps between rewards each time. If, because of his enthusiasm, he begins to charge ahead, stop him and immediately reward him for halting. This will insure that he keeps his attention on you and the task at hand. This methodical, deliberate process is setting the stage for a positive and healthy working relationship with your equine.

This is how you begin with leading training, and also how you should proceed with all the new things that you will be teaching your equine. In the beginning of leading training, he gets rewarded for even an assimilation of what you’re asking. For example, when you get to negotiating obstacles, your goal may be to cross over a bridge, but when your equine sees the bridge ahead, he may stop or start backing up. At this point, allow him to back until he stops. Go back and repeat the steps you did prior to approaching the obstacle. Then, asking for only one step at a time, proceed as you did during his flatwork leading training toward the bridge, rewarding each step he takes. Tell him verbally how brave he is and continue to reward any steps he takes toward the obstacle before proceeding forward. Remember to stop at any interval where he becomes tense, ask for one more step to be rewarded, and then allow him to settle and refocus before asking any more from him.

This is how you begin with leading training, and also how you should proceed with all the new things that you will be teaching your equine. In the beginning of leading training, he gets rewarded for even an assimilation of what you’re asking. For example, when you get to negotiating obstacles, your goal may be to cross over a bridge, but when your equine sees the bridge ahead, he may stop or start backing up. At this point, allow him to back until he stops. Go back and repeat the steps you did prior to approaching the obstacle. Then, asking for only one step at a time, proceed as you did during his flatwork leading training toward the bridge, rewarding each step he takes. Tell him verbally how brave he is and continue to reward any steps he takes toward the obstacle before proceeding forward. Remember to stop at any interval where he becomes tense, ask for one more step to be rewarded, and then allow him to settle and refocus before asking any more from him.

Once he goes to the bridge without a problem, you no longer have to reward him all the way up to the bridge. Just reward him when he actually gets to the bridge. Next, step up onto the bridge and ask him to take a step up onto the bridge with his two front feet, which is another new task. If he puts one foot on the bridge or even tries to lift up a foot and put it on the bridge, make sure you reward that behavior. Once he has a foot firmly placed on the bridge, keep tension on the lead rope and ask for his other front foot to come up onto the bridge. If he places his second foot on the bridge, you can then reward him for having both front feet on the bridge. Next, you’re going to continue forward and just walk over the bridge to the other side, pause and reward. Then quit this lesson. In his next lesson, if needed, repeat the approach the same way if he starts to balk. If not, ask him to step both front feet up onto the bridge, stop, make sure he is standing squarely, and reward that behavior.

Now you no longer need to reward for one foot on the bridge. This is called “fading or phasing out” the reward for a previous behavior (one step), while introducing the new behavior of walking to the bridge, halting and then putting two front feet up on the bridge. Wait for a moment for him to chew his reward and then ask him to continue onto the bridge, stop and square up with four feet on the bridge and reward. If he does not comply and won’t stop on the bridge, just go back to the beginning, approach the bridge as described and try again until he stops to be rewarded with all four feet placed squarely on the bridge

Now you no longer need to reward for one foot on the bridge. This is called “fading or phasing out” the reward for a previous behavior (one step), while introducing the new behavior of walking to the bridge, halting and then putting two front feet up on the bridge. Wait for a moment for him to chew his reward and then ask him to continue onto the bridge, stop and square up with four feet on the bridge and reward. If he does not comply and won’t stop on the bridge, just go back to the beginning, approach the bridge as described and try again until he stops to be rewarded with all four feet placed squarely on the bridge

Then you ask him, to place his two front feet on the ground while leaving his two back feet on the bridge. Then have him stop and square up to be rewarded. This is a difficult position and if he cannot succeed by the third attempt, you may have to step in front and aid in his balance, then reward him when he settles in this position.

The last step over the bridge is to bring the hind feet off the bridge, stop and square up one more time before he gets rewarded. This does two things. It causes your equine to be attentive to the number of steps you are asking and it puts him in good posture at each stage so that his body will develop properly. In future lessons, the steps in the approach to the bridge no longer need to be rewarded and as he becomes more attentive, he will learn to stop any time you ask and wait for your cue to proceed. After several months of this meticulous attention to these detailed steps, he will not necessarily need to be rewarded with the food reward each time—a pat on the neck and kind words of support should be sufficient. Rewards can then be given for whole “blocks” of steps when he successfully completes them.

The last step over the bridge is to bring the hind feet off the bridge, stop and square up one more time before he gets rewarded. This does two things. It causes your equine to be attentive to the number of steps you are asking and it puts him in good posture at each stage so that his body will develop properly. In future lessons, the steps in the approach to the bridge no longer need to be rewarded and as he becomes more attentive, he will learn to stop any time you ask and wait for your cue to proceed. After several months of this meticulous attention to these detailed steps, he will not necessarily need to be rewarded with the food reward each time—a pat on the neck and kind words of support should be sufficient. Rewards can then be given for whole “blocks” of steps when he successfully completes them.

Here is a question a lot of people ask: “This is fine while my animal and I are still working from the ground, but what happens when I finally get on to ride? Do I keep rewarding every new behavior when I ride?” The answer to that question is, “No, you don’t.” If you do your ground work correctly, it will address all the things that you’ll be doing while you’re riding before you actually even get on. Your equine has been lavishly rewarded for stopping when you pull on the reins and the drive lines, and he’s been rewarded for turning and backing and everything else he needs to learn before you actually get on him, so the only thing left to get used to would be exposure to your legs on his sides. He will soon learn that your legs push him in the direction of the turn you are indicating with your reins. For this action, he does not need to be rewarded.

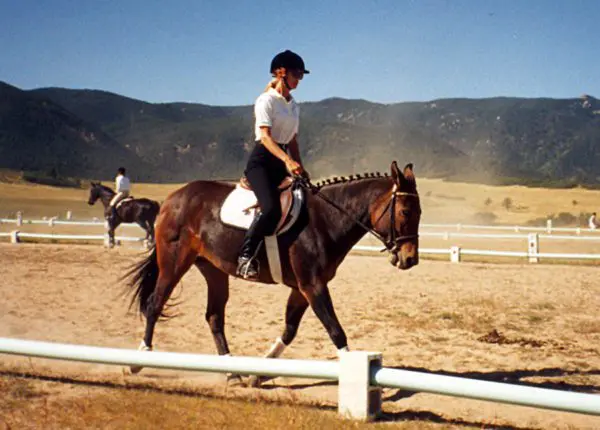

In the natural progression of correct training—including during mounting training—your equine should also be getting rewarded when you’re first getting him used to your being on-board. Give him the oats reward for standing still while you attempt to mount (i.e., walking toward him, holding the left rein and reaching for the saddle horn), and then when you hang from each side of his body with a foot in the stirrup (first on one side and then on the other side), and, finally, from each side of his body while you sit on his back. When you ask him to turn his head to take the oats from your hand, you can be sure his attention will be on you because this action will force him to look at you in order to receive his oats. Then reward him again for standing still as you dismount. Consequently, by the time you actually get to the point of riding in an open arena, he’s been rewarded for having you on his back and for behaving well through all the exercises demanded from him during round pen training.

In the natural progression of correct training—including during mounting training—your equine should also be getting rewarded when you’re first getting him used to your being on-board. Give him the oats reward for standing still while you attempt to mount (i.e., walking toward him, holding the left rein and reaching for the saddle horn), and then when you hang from each side of his body with a foot in the stirrup (first on one side and then on the other side), and, finally, from each side of his body while you sit on his back. When you ask him to turn his head to take the oats from your hand, you can be sure his attention will be on you because this action will force him to look at you in order to receive his oats. Then reward him again for standing still as you dismount. Consequently, by the time you actually get to the point of riding in an open arena, he’s been rewarded for having you on his back and for behaving well through all the exercises demanded from him during round pen training.

You may first want to lunge your equine when you move into the open arena. Lunge him on the lunge line and reward him during that part of your arena workout. When you are ready to mount in the open arena, have a few oats in your pockets to offer him when you mount on each side the first few times. This will ensure that his attention stays focused on you. Once he is used to being ridden, you will no longer have to reward him in the middle of riding lessons. If he does not keep his attention on his work in the open arena, this signifies that not enough time has been spent on the ground work and you should back up your training regimen to the point that he is maintaining attentiveness and performing correctly, even if it means going back to the round pen or leading work. If, in the ground work stages, you give plenty of food rewards in the correct manner, by the time you groom and tack up, your equine should have been sufficiently rewarded and will not require another reward until after your workout when you return to the work station and un-tack him. This is called delayed gratification. When you un-tack him and do your last minute grooming before putting him away, again be generous with the crimped oats and praise your equine for a job well done. Rewards are dispensed very specifically and pave the road to a solid foundation of trust and friendship.

To learn more about Meredith Hodges and her comprehensive all-breed equine training program, visit LuckyThreeRanch.com, MEREDITH HODGES PUBLIC FIGURE Facebook page, or call 1-800-816-7566. Check out her children’s website at JasperTheMule.com. Also, find Meredith on Pinterest, Instagram, MeWe, YouTube and Twitter.

© 2013, 2016, 2018, 2021, 2022 Lucky Three Ranch, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Meredith gets a lot of letters and emails from people with training questions about their equines. Here, she discusses how to set up a work station for tack and grooming your equine.

By Meredith Hodges

Most equines can be taught to carry a rider in a relatively short time. However, just because they are compliant doesn’t mean their body is adequately prepared for what they will be asked to do and that they are truly mentally engaged in your partnership. We can affect our equine’s manners and teach them to do certain movements and in most cases, we will get the response that we want…at least for the moment. Most of us grow up thinking that getting the animal to accept a rider is a reasonable goal and we are thrilled when they quickly comply. When I was first training equines, I even thought that to spare them the weight of the rider when they were younger and that it would be more beneficial to drive them first as this seemed less stressful for them. Of course, I was then unaware of the multitude of tiny details that were escaping my attention due to my limited education. I had a lot to learn.

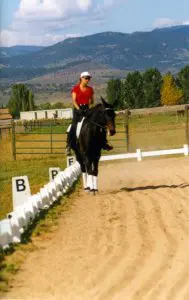

Because my equines reacted so well during training, I had no reason to believe that there was anything wrong with my approach until I began showing them. I started to experience resistant behaviors in my animals that I promptly attributed to simple disobedience. I had no reason to believe that I wasn’t being kind and patient until I met my dressage instructor, Melinda Weatherford. I soon learned that complaining about Sundowner’s negative response to his dressage lessons and blaming HIM was not going to yield any shortcuts to our success. The day she showed up with a big button on her lapel that said, “No Whining” was the end of my complaining and impatience, and the beginning of my becoming truly focused on the tasks at hand. I learned that riding through (and often repeating) mistakes did not pose any real solutions to our problems. I attended numerous clinics from all sorts of notable professionals and we improved slowly, but a lot of the problems were still present. Sundowner would still bolt and run when things got a bit awkward, but he eventually stopped bolting once I changed my attitude and approach, and when he was secure in his core strength in good equine posture.

Because my equines reacted so well during training, I had no reason to believe that there was anything wrong with my approach until I began showing them. I started to experience resistant behaviors in my animals that I promptly attributed to simple disobedience. I had no reason to believe that I wasn’t being kind and patient until I met my dressage instructor, Melinda Weatherford. I soon learned that complaining about Sundowner’s negative response to his dressage lessons and blaming HIM was not going to yield any shortcuts to our success. The day she showed up with a big button on her lapel that said, “No Whining” was the end of my complaining and impatience, and the beginning of my becoming truly focused on the tasks at hand. I learned that riding through (and often repeating) mistakes did not pose any real solutions to our problems. I attended numerous clinics from all sorts of notable professionals and we improved slowly, but a lot of the problems were still present. Sundowner would still bolt and run when things got a bit awkward, but he eventually stopped bolting once I changed my attitude and approach, and when he was secure in his core strength in good equine posture.

I thought about what my grandmother had told me years ago about being polite and considerate with everything I did. Good manners were everything to her and I thought I was using good manners. I soon found that good manners were not the only important element of communication. Empathy was another important consideration…to put oneself in the other “person’s” shoes, and that could be attributed to animals as well. So, I began to ask myself how it would feel to me if I was approached and treated the way I was treating my equines. My first epiphany was during grooming. It occurred to me that grooming tools, like a shedding blade, might not feel very  good unless I was careful about the way I used it. Body clipping was much more tolerable for them if I did the hard-to-get places first and saved the general body for last. Standing for long periods of time certainly did not yield a calm, compliant attitude when the more tedious places were left until last. After standing for an hour or more, the animal got antsy when I was trying to do more detailed work around the legs, head, flanks and ears after the body; so I changed the order. Generally speaking, I slowed my pace and eliminated any abrupt movements on my part to give the equine adequate time to assess what I would do next and approached each task very CAREFULLY. The results were amazing! I could now groom, clip bridle paths and fly spray everyone with no halters, even in their turnout areas as a herd. They were all beginning to really trust me.

good unless I was careful about the way I used it. Body clipping was much more tolerable for them if I did the hard-to-get places first and saved the general body for last. Standing for long periods of time certainly did not yield a calm, compliant attitude when the more tedious places were left until last. After standing for an hour or more, the animal got antsy when I was trying to do more detailed work around the legs, head, flanks and ears after the body; so I changed the order. Generally speaking, I slowed my pace and eliminated any abrupt movements on my part to give the equine adequate time to assess what I would do next and approached each task very CAREFULLY. The results were amazing! I could now groom, clip bridle paths and fly spray everyone with no halters, even in their turnout areas as a herd. They were all beginning to really trust me.

There was still one more thing my grandmother had said that echoed in my brain, “You are going to be a sorry old woman if you do not learn to stand up straight and move in good posture!” Good posture is not something that we are born with. It is something that must be learned and practiced repetitiously so that it becomes habitual for it to really contribute to your overall health. Good posture begins at the core, “the innermost, essential part of anything.” In a human being, it lies behind the belly button amongst the vital organs and surrounded by the skeletal frame. In a biped, upon signals from the brain, energy impulses run from the core and up from the waist, and simultaneously down through the lower body and  legs. The core of an equine is at the center of balance in the torso. Similar to bipeds, they need the energy to run freely along the hindquarters and down through the hind legs to create a solid foundation from which to allow the energy in front to rise into suspension to get the most efficient movement. When their weight is shifted too much onto the front end, their ability to carry a rider efficiently and correctly is compromised. To achieve correct energy flow and efficient movement, the animal’s internal supportive structures need to be conditioned in a symmetrical way around the skeletal frame. People can do this by learning to walk with a book on their head and with Pilates exercises, but how can we affect this same kind of conditioning in a quadruped?

legs. The core of an equine is at the center of balance in the torso. Similar to bipeds, they need the energy to run freely along the hindquarters and down through the hind legs to create a solid foundation from which to allow the energy in front to rise into suspension to get the most efficient movement. When their weight is shifted too much onto the front end, their ability to carry a rider efficiently and correctly is compromised. To achieve correct energy flow and efficient movement, the animal’s internal supportive structures need to be conditioned in a symmetrical way around the skeletal frame. People can do this by learning to walk with a book on their head and with Pilates exercises, but how can we affect this same kind of conditioning in a quadruped?

The first issue I noticed was with leading our animals. When we lead our animals with the lead rope in the right hand, we drop our shoulder and are no longer in good posture. When we walk, our hand moves ever so slightly from left to right as we walk; we inadvertently move the equine’s head back and forth. They balance with their head and neck. Thus, we are forcing them off balance with every step that we take. Since movement builds muscle, they are being asymmetrically conditioned internally and externally with every step we take together. In order to correct this, we must allow the animal to be totally in control of his own body as we walk together. We are cultivating proprioception or “body awareness.”

During the time you do the core strength leading exercises, you should NOT ride the animal as this will inhibit the success of these preliminary exercises. It will not result in the same symmetrical muscle conditioning, habitual behavior and new way of moving. For the best results, lessons need to be routine and done in good posture from the time you take your equine from the pen until the time you put him away. Hold the lead rope in your LEFT hand, keeping slack in the lead rope. Keep his head at your shoulder, match your steps with his front legs, point in the direction of travel with your right hand and look where you are going. Carry his reward of oats in a fanny pack around your waist; he’s not likely to bolt if he knows his reward is right there in the fanny pack.

Plan to move in straight lines and do gradual turns that encourage him to stay erect and bend through his rib cage, keeping an even distribution of weight through all four feet. Square him up with equal weight over all four feet EVERY TIME you stop and reward him with oats from your fanny pack. Then wait patiently for him to finish chewing. We are building NEW habits in the equine’s way of moving and the only way that can change is through routine, consistency in  the routine and correctness in the execution of the exercises. Since this requires that you be in good posture as well, you will also reap the benefits from this regimen. Along with feeding correctly (explained on my website at www.luckythreeranch.com), these exercises will help equines to drop fat rolls and begin to develop the top line and abdominal strength in good posture. The spine will then be adequately supported to easily accept a rider. He will be better able to stand still as you pull on the saddle horn to mount.

the routine and correctness in the execution of the exercises. Since this requires that you be in good posture as well, you will also reap the benefits from this regimen. Along with feeding correctly (explained on my website at www.luckythreeranch.com), these exercises will help equines to drop fat rolls and begin to develop the top line and abdominal strength in good posture. The spine will then be adequately supported to easily accept a rider. He will be better able to stand still as you pull on the saddle horn to mount.

When the body is in good posture, all internal organs can function properly and the skeletal frame will be supported correctly throughout his entire body. This will greatly minimize joint problems, arthritis and other anomalies that come from asymmetrical development and compromises in the body. Just as our children need routine, ongoing learning and the right kind of exercise while they are growing up, so do equines. They need boundaries for their behavior clearly outlined to minimize anxious behaviors and inappropriate behavior. The exercises that you do together need to build strength and coordination in good equine posture. The time spent together during leading training and going forward, slowly builds a good solid relationship with your equine and fosters his confidence and trust in you. He will know it is you who actually helps him to feel physically much better than he ever has.

Core muscle strength and balance must be done through correct leading exercises on flat ground. Coordination can be added to his overall carriage with the addition of negotiating obstacles on the lead rope done the same way. Once familiar with the obstacles, you will need to break them down into very small segments where the equine is asked to randomly halt squarely every couple of steps through the obstacle. You can tell when you have successfully achieved core strength in good balance, when your equine will perform accurately with the lead rope slung over his neck. He will stay at your shoulder, respond to hand signals and body language only and does what is expected perfectly. A carefully planned routine coupled with an appropriate feeding program is critical to your equine’s healthy development.

The task at the leading stage is not only to teach them to follow, but to have your equine follow with his head at your shoulder as you define straight lines and gradual arcs that will condition his body symmetrically on all sides of the skeletal frame. This planned course of action also begins to develop a secure bond between you. Mirror the steps of his front legs as you go through the all movements keeping your own body erect and in good posture. Always look in the direction of travel and ask him to square up with equal weight over all four feet every time he stops and reward him. This kind of leading training develops strength and balance in the equine body at the deepest level so strengthened muscles will hold the bones, tendons, ligaments and even cartilage in correct alignment. Equines that are not in correct equine posture will have issues involving organs, joints, hooves and soft tissue trauma. This is why it is so important to spend plenty of time perfecting your techniques every time you lead your equine.

The task at the leading stage is not only to teach them to follow, but to have your equine follow with his head at your shoulder as you define straight lines and gradual arcs that will condition his body symmetrically on all sides of the skeletal frame. This planned course of action also begins to develop a secure bond between you. Mirror the steps of his front legs as you go through the all movements keeping your own body erect and in good posture. Always look in the direction of travel and ask him to square up with equal weight over all four feet every time he stops and reward him. This kind of leading training develops strength and balance in the equine body at the deepest level so strengthened muscles will hold the bones, tendons, ligaments and even cartilage in correct alignment. Equines that are not in correct equine posture will have issues involving organs, joints, hooves and soft tissue trauma. This is why it is so important to spend plenty of time perfecting your techniques every time you lead your equine.

The equine then needs to build muscle so he can sustain his balance on the circle without the rider before he will be able to balance with a rider. An equine that has not had time in the round pen to establish strength, coordination and balance on the circle, with the help of our postural restraint called the “Elbow Pull,” will have difficulty as he will be pulled off balance with even the slightest pressure. He will most likely raise his head, hollow his back and lean like a motorcycle into the turns. When first introduced to the “Elbow Pull,” his first lesson in the round pen should only be done at the walk to teach him to give to its pressure, arch his back and stretch his spine while tightening his abs. If you ask for trot and he resists against the “Elbow Pull,” just go back to the walk until he can consistently sustain this good posture while the “Elbow Pull” stays loose. He can gain speed and difficulty as his proficiency increases.

Loss of balance will cause stress, and even panic that can result in him pulling the lead rope, lunge line or reins under saddle right out of your hands and running off. This is not disobedience, just fear from a loss of balance and it should not be punished, just ignored and then calmly go back to work. The animal that has had core strength built through leading exercises, lunging on the circle and ground driving in the “Elbow Pull” before riding, will not exhibit these seemingly disobedient behaviors. Lunging will begin to develop hard muscle over the core muscles and internal supportive structures you have spent so many months strengthening during leading training exercises. It will further enhance your equine’s ability to perform and stay balanced in action, and play patterns in turnout will begin to change dramatically as this becomes his habitual way of going. Be sure to be consistent with verbal commands during all these beginning stages as they set the stage for better communication and exceptional performance later. Although you need to spend more time in his beginning training than you might want to, this will also add to your equine’s longevity and use-life by as much as 5-10 years. The equine athlete that has a foundation of core strength in good equine posture, whether used for pleasure or show, will be a much more capable and safe performer than one that has not, and he will always be grateful to YOU for his comfort.

Loss of balance will cause stress, and even panic that can result in him pulling the lead rope, lunge line or reins under saddle right out of your hands and running off. This is not disobedience, just fear from a loss of balance and it should not be punished, just ignored and then calmly go back to work. The animal that has had core strength built through leading exercises, lunging on the circle and ground driving in the “Elbow Pull” before riding, will not exhibit these seemingly disobedient behaviors. Lunging will begin to develop hard muscle over the core muscles and internal supportive structures you have spent so many months strengthening during leading training exercises. It will further enhance your equine’s ability to perform and stay balanced in action, and play patterns in turnout will begin to change dramatically as this becomes his habitual way of going. Be sure to be consistent with verbal commands during all these beginning stages as they set the stage for better communication and exceptional performance later. Although you need to spend more time in his beginning training than you might want to, this will also add to your equine’s longevity and use-life by as much as 5-10 years. The equine athlete that has a foundation of core strength in good equine posture, whether used for pleasure or show, will be a much more capable and safe performer than one that has not, and he will always be grateful to YOU for his comfort.

To learn more about Meredith Hodges and her comprehensive all-breed equine training program, visit LuckyThreeRanch.com, MEREDITH HODGES PUBLIC FIGURE Facebook page, or call 1-800-816-7566. Check out her children’s website at JasperTheMule.com. Also, find Meredith on Pinterest, Instagram, MeWe, YouTube and Twitter.

Covered in TRAINING MULES & DONKEY: A LOGICAL APPROACH TO TRAINING, TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE and EQUUS REVISITED at www.luckythreeranchstore.com

© 2018, 2024 Lucky Three Ranch, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

(A SELF-CORRECTING POSTURAL AID FOR EQUINES)

Concept Developed by Richard Shrake and Specific Design by Meredith Hodges

(Trademarked & Published in TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE 2003)

In my TRAINING MULES & DONKEYS DVD #2, in the TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE manual (2003) and in the SPECIAL FEATURES of my EQUUS REVISITED DVD (2009), I talk about using a postural aid called the “Elbow Pull.” In the EQUUS REVISITED DVD, we teach you how to measure it for your individual equine and how to make it. If you have our video series, in DVD #2, in the TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE manual (2003) and in the EQUUS REVISITED DVD (2009), we talk about using the “Elbow Pull.” We teach you how to measure it for your individual equine and how to make it. The “Elbow Pull” puts your animal into your equine’s ideal posture. He will have full range of motion in every direction when it is adjusted correctly. He will just not be able to raise his head so high that he hollows his neck and back.

In my TRAINING MULES & DONKEYS DVD #2, in the TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE manual (2003) and in the SPECIAL FEATURES of my EQUUS REVISITED DVD (2009), I talk about using a postural aid called the “Elbow Pull.” In the EQUUS REVISITED DVD, we teach you how to measure it for your individual equine and how to make it. If you have our video series, in DVD #2, in the TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE manual (2003) and in the EQUUS REVISITED DVD (2009), we talk about using the “Elbow Pull.” We teach you how to measure it for your individual equine and how to make it. The “Elbow Pull” puts your animal into your equine’s ideal posture. He will have full range of motion in every direction when it is adjusted correctly. He will just not be able to raise his head so high that he hollows his neck and back.

He will be able to balance and adjust his body position, encourage the hind quarters to come underneath his body when he is walked, or driven forward. Allowing the equine take short steps, front and back, would let the back sag (swayback-Lordosis) and does not engage the abdominal muscles. The “Elbow Pull” encourages the equine to stretch his spine, round his back and neck upwards (not “hump” it!) and elevates the shoulders when he steps  underneath his body. The elevation (or suspension) in the shoulders allows him to increase the “reach” in his front legs. I use the “Elbow Pull” for Leading Training, Ground Driving and when he is ready, Lunging in the Round Pen. The Leading Training on flat ground through our HOURGLASS PATTERN positively affects his overall postural balance, and Leading through Obstacles adds coordination. You know that he is ready to go on to each stage of Leading Training on flat ground (and then through obstacles) when you can throw the lead rope over his neck and do the exercises with verbal commands, hand signals and body language alone. This is building a new habitual way of traveling is all in preparation for Lunging correctly…keeping his body erect and in a symmetrical balance while he bends to the arc of the circle through his torso without leaning like a motorcycle. It will prevent muscle compromises throughout his body that could cause soreness and compromise organ function.

underneath his body. The elevation (or suspension) in the shoulders allows him to increase the “reach” in his front legs. I use the “Elbow Pull” for Leading Training, Ground Driving and when he is ready, Lunging in the Round Pen. The Leading Training on flat ground through our HOURGLASS PATTERN positively affects his overall postural balance, and Leading through Obstacles adds coordination. You know that he is ready to go on to each stage of Leading Training on flat ground (and then through obstacles) when you can throw the lead rope over his neck and do the exercises with verbal commands, hand signals and body language alone. This is building a new habitual way of traveling is all in preparation for Lunging correctly…keeping his body erect and in a symmetrical balance while he bends to the arc of the circle through his torso without leaning like a motorcycle. It will prevent muscle compromises throughout his body that could cause soreness and compromise organ function.

I continue to use the “Elbow Pull” with each new stage of training to help him maintain his good posture throughout the different tasks. It is a supportive device and when he has problems with his posture, it will become tight. He can “lean” against it for a few strides without going totally out of good posture which gives him relief from the stress of trying to hold his good posture for long periods of time, which is often difficult in the beginning.

When he is again able to hold his good posture, the aid becomes loose all over. The equine is in complete control of this postural aid. Even people have problems maintaining good posture without the occasional reminder of their own good posture until it becomes more habitual.

None of us were born in good posture. It is something that must be taught. If we are allowed to “slouch” in our posture, it WILL create soreness and physical problems over time, especially when we get much older. After Lunging in good posture for several months, the equine’s habitual way of going will be changed. He will begin to travel in good posture automatically.

None of us were born in good posture. It is something that must be taught. If we are allowed to “slouch” in our posture, it WILL create soreness and physical problems over time, especially when we get much older. After Lunging in good posture for several months, the equine’s habitual way of going will be changed. He will begin to travel in good posture automatically.

Changing habits takes a long time of repetitive behavior to evolve into a new habitual way of acting. As you teach your body through these stages to stay in sync with your equine’s steps, YOUR body becomes more in tune with his way of going and prepares you to be a better rider. This is all a matter or re-programming brain-muscle impulses. The equine will be Ground Driven in the “Elbow Pull” as he adjusts to learning rein cues, and when the weight of the rider is finally added, it is advisable to ride in the “Elbow Pull” until it remains loose all the time. When it does, you can be sure he is strong in his core balance and truly ready to support the rider in any kind of athletic pursuit. The equine learns to carry the rider on top of an upward arc in their spine with the abdominal muscles engaged. This is the same as teaching people to use their whole body correctly and lift with  their legs and not their backs. These kinds of exercises make sure that the animal travels symmetrically, allowing the joints to work as they were designed to do (according to the laws of physics) with no compromises, and promotes optimum function of their internal organs.

their legs and not their backs. These kinds of exercises make sure that the animal travels symmetrically, allowing the joints to work as they were designed to do (according to the laws of physics) with no compromises, and promotes optimum function of their internal organs.

With an equine that is over 2 years old and that has not had the benefit of developing core strength in good posture, it is advisable to first use the “Elbow Pull” during detailed and extensive Leading Lessons, both on the flat ground and later over obstacles. An equine under two years of age will not need the “Elbow Pull” support while working on his way of going since repetitive habits have not yet been fully established.

Lunge the equine in the Round Pen for several months until the animal habitually exhibits an erect posture with equal weight over all four feet and balanced self-body carriage. When you finally begin riding, you should use the “Elbow Pull” while you are riding our Hourglass Pattern under saddle as he adjusts to the added weight and new balance. When the “Elbow Pull” is adjusted correctly and the equine is in good posture, it will not put any pressure on the animal at all. When he is out of good posture, it puts pressure on the poll, the bit rings, behind the forearms and over the back. He will go back to his good posture as soon as he is able in order to release the pressure points.

Lunge the equine in the Round Pen for several months until the animal habitually exhibits an erect posture with equal weight over all four feet and balanced self-body carriage. When you finally begin riding, you should use the “Elbow Pull” while you are riding our Hourglass Pattern under saddle as he adjusts to the added weight and new balance. When the “Elbow Pull” is adjusted correctly and the equine is in good posture, it will not put any pressure on the animal at all. When he is out of good posture, it puts pressure on the poll, the bit rings, behind the forearms and over the back. He will go back to his good posture as soon as he is able in order to release the pressure points.

Place the “Elbow Pull” over the poll, through the snaffle bit rings, between the animal’s front legs and over the back, then snap the two ends to a surcingle D-ring or D-rings, on the saddle you are using. It should be adjusted so he can only raise his head approximately 3-4 inches above the level of the withers (just before he hollows his neck and back). The “Elbow Pull” needs to be adjusted loosely enough so that he can relieve the pressure at the poll, bit rings, elbows and back without having to drop his head below the withers.

Place the “Elbow Pull” over the poll, through the snaffle bit rings, between the animal’s front legs and over the back, then snap the two ends to a surcingle D-ring or D-rings, on the saddle you are using. It should be adjusted so he can only raise his head approximately 3-4 inches above the level of the withers (just before he hollows his neck and back). The “Elbow Pull” needs to be adjusted loosely enough so that he can relieve the pressure at the poll, bit rings, elbows and back without having to drop his head below the withers.

When lunging, if the “Elbow Pull” is correctly adjusted and he still wants to carry his nose to the ground, encouraging him with the whip to speed him up a bit. This will encourage him to engage his hindquarters and raise his head into the correct position. The only way he can really go forward with his nose to the ground is if the hind quarters are not engaged. As soon as the hindquarters are engaged, he will have to raise his head to the correct position to maintain his balance. When being led in the “Elbow Pull,” lowering the head is not a problem because you will have control of the lead rope attached a ring underneath his noseband or a halter (not attached to the bit!). Doing stretching-down exercises during leading training helps to stretch the spine and alleviate any soreness that could be developing with the new postural position. Breaking old habitual muscle positions can cause soreness to begin with, but as the better posture becomes more evolved, it also becomes much more comfortable (as it does in humans). Stay away from medications as much as possible as he works his way to the new posture.

In the Round Pen, the “Elbow Pull” helps the animal learn to travel in good equine posture without the added weight of a rider first. In doing so, it increases his core strength and the ability for him to carry a more balanced posture of his own volition. The added weight of the rider under saddle will challenge the animal again to maintain this good posture. This will take further strengthening of the muscles. The “Elbow Pull” will keep the animal in the correct posture while carrying the rider, so he doesn’t ever build muscle out of balance and out of good equine posture. When you do this, you are changing old habitual movement into good equine posture and a balanced way of moving. This eventually (after two years) will become his habitual way of moving and playing, even during turnout.

In the Round Pen, the “Elbow Pull” helps the animal learn to travel in good equine posture without the added weight of a rider first. In doing so, it increases his core strength and the ability for him to carry a more balanced posture of his own volition. The added weight of the rider under saddle will challenge the animal again to maintain this good posture. This will take further strengthening of the muscles. The “Elbow Pull” will keep the animal in the correct posture while carrying the rider, so he doesn’t ever build muscle out of balance and out of good equine posture. When you do this, you are changing old habitual movement into good equine posture and a balanced way of moving. This eventually (after two years) will become his habitual way of moving and playing, even during turnout.

Your equine should stay in the “Elbow Pull” when working for two years to make sure that the muscles are indeed conditioned around correct equine posture through correct and consistent repetition. This means that when your year of Lunging, then Ground Driving is over, and he begins to work with a rider or while being driven, you would still use the “Elbow Pull” to help him stay in good posture for another year with the added weight of the rider on his back. If driving your equine, you should also use it during the first two years in your driving arena during training to promote good equine driving posture and engagement of the hind quarters while pulling. This assures that the muscles are becoming correctly and symmetrically strong (supporting the skeleton), over a balanced and physically aligned frame.

If you are consistent during his lessons, being in good equine posture will become his normal way of going and will not disappear when you finally ride without it.

If you are consistent during his lessons, being in good equine posture will become his normal way of going and will not disappear when you finally ride without it.

The “Elbow Pull” postural aid does not pull their head down. Rather, it gives them full range of motion (up, down, and sideways), but keeps them from raising their heads so high that they hollow their back and neck during initial training. It is a fully self-correcting restraint that gives them something to lean on when they are not yet strong enough in the core (elements that support the skeletal frame…muscles, tendons, ligaments, connective tissue and even cartilage in the joints) to maintain their ideal balance. It encourages them to step well underneath their body, round their back upward from head to tail and puts the spine in an position to allow space between the vertebrae Spinus Processes (and avoid “Kissing Spine”) and to prevent the rider from injuring their spine (according to the laws of Physics). The “Elbow Pull” provides support much like a balance bar does for a beginning ballet dancer, and the principles of good posture are the same as with humans.

and to prevent the rider from injuring their spine (according to the laws of Physics). The “Elbow Pull” provides support much like a balance bar does for a beginning ballet dancer, and the principles of good posture are the same as with humans.

Repetition and consistency during training can change habitual bad posture to habitual good posture over a long period of time, usually about two years. Good posture and correct movement can enhance longevity by as much as 5-10 years, enable internal organs to operate efficiently and prevent calcification, arthritis and other compromises like locked stifles that can create soreness in the body.

There is a much different way to secure the “Elbow Pull on a horse. Horses have violent reactions to a hard tie, so  you will need to cross the rope across their back, pull it taut into the correct tension and then secure the snaps, keeping plenty of slack in the rope. You want the rope semi-knot to slip if they brace against it, but you do not want loose snaps on the ends of the rope to swing free to hit the horse anywhere on his body. With horses, you would just twist the rope over the back as shown in the photo, so the snaps are a moot point until the horse learns to give to the Elbow Pull and can be hard tied.

you will need to cross the rope across their back, pull it taut into the correct tension and then secure the snaps, keeping plenty of slack in the rope. You want the rope semi-knot to slip if they brace against it, but you do not want loose snaps on the ends of the rope to swing free to hit the horse anywhere on his body. With horses, you would just twist the rope over the back as shown in the photo, so the snaps are a moot point until the horse learns to give to the Elbow Pull and can be hard tied.

Making the “Elbow Pull”

Although the “Elbow Pull” is a very simple and straight forward aid to help keep your equine in good posture, it is also a device that needs to be custom made to fit each individual equine. Equines that approximate the same size in the front quarters will probably be able to use the same one. First, you need to obtain a package of 3/8″ X 50′ nylon and polyester twisted rope. This is the way it is sold. Do not substitute any other kind of rope, or leather reins, etc. as this will have a different weight and slippage around the bridle and will not have the same effect.

Although the “Elbow Pull” is a very simple and straight forward aid to help keep your equine in good posture, it is also a device that needs to be custom made to fit each individual equine. Equines that approximate the same size in the front quarters will probably be able to use the same one. First, you need to obtain a package of 3/8″ X 50′ nylon and polyester twisted rope. This is the way it is sold. Do not substitute any other kind of rope, or leather reins, etc. as this will have a different weight and slippage around the bridle and will not have the same effect.

You will also need two snaps that are narrow, yet fairly strong that can fit easily through the D-rings on your surcingle, or Western saddle. English saddle D-rings are generally too small and in this situation, we do not attach to them, but rather attach the “Elbow Pull” to itself over the top of the spine. If the rope tends to twist and the snaps slide off to the side, you can often just snap one snap to the D-ring and the other snap snapped to the first snap, or if the “Elbow Pull” is a bit shorter, you can just snap it to the small D-ring on each side. The reason for twisted rope is so you can actually go through the D-rings and snap it into the twisted rope itself for a more exact setting. You would just untwist the rope at the setting point and snap into the middle of the rope so it won’t slide.

You will also need two snaps that are narrow, yet fairly strong that can fit easily through the D-rings on your surcingle, or Western saddle. English saddle D-rings are generally too small and in this situation, we do not attach to them, but rather attach the “Elbow Pull” to itself over the top of the spine. If the rope tends to twist and the snaps slide off to the side, you can often just snap one snap to the D-ring and the other snap snapped to the first snap, or if the “Elbow Pull” is a bit shorter, you can just snap it to the small D-ring on each side. The reason for twisted rope is so you can actually go through the D-rings and snap it into the twisted rope itself for a more exact setting. You would just untwist the rope at the setting point and snap into the middle of the rope so it won’t slide.

Have the equine stand at the hitch rail with the snaffle bridle on. To get a measurement for how long a piece of rope you will need for his “Elbow Pull,” take a length of rope from the coil. Feed the end of the rope from the inside to the outside of the snaffle bit ring, drape it over the poll of your equine and feed it from the outside of the snaffle bit ring to the inside on the opposite side of your equine. Then pull enough slack to go down through the front legs, behind the forearm, up and over the back such that it hangs one foot, or more (but not less) on the other side of the spine. Then, go back to the side on which you started and do the same on that side with the remainder of the 50″ foot length of rope and cut the rope at the 1-foot mark on the other side of the spine.

Have the equine stand at the hitch rail with the snaffle bridle on. To get a measurement for how long a piece of rope you will need for his “Elbow Pull,” take a length of rope from the coil. Feed the end of the rope from the inside to the outside of the snaffle bit ring, drape it over the poll of your equine and feed it from the outside of the snaffle bit ring to the inside on the opposite side of your equine. Then pull enough slack to go down through the front legs, behind the forearm, up and over the back such that it hangs one foot, or more (but not less) on the other side of the spine. Then, go back to the side on which you started and do the same on that side with the remainder of the 50″ foot length of rope and cut the rope at the 1-foot mark on the other side of the spine.

Once you have the proper length of rope for your equine, you will need to unravel 3” – 4″ of one end of the rope and loop it through the ring on your first snap. Then you will braid the rope back into itself. First, pick the loose strand that is on top as you lay the rope across your hand, bend it around the end of the snap and feed it under a twist of the rope such that it creates a loop around the end of your snap and pull it snug. Then take the next loose strand (which would be the middle of the three strands) and feed it under the next twist down from the one you just did. Then do the same with the third loose strand under the third twist in the rope. Take all three strands in your hand, hold the rope so it doesn’t twist and pull all three strands snug. They should all line up.

Once you have the proper length of rope for your equine, you will need to unravel 3” – 4″ of one end of the rope and loop it through the ring on your first snap. Then you will braid the rope back into itself. First, pick the loose strand that is on top as you lay the rope across your hand, bend it around the end of the snap and feed it under a twist of the rope such that it creates a loop around the end of your snap and pull it snug. Then take the next loose strand (which would be the middle of the three strands) and feed it under the next twist down from the one you just did. Then do the same with the third loose strand under the third twist in the rope. Take all three strands in your hand, hold the rope so it doesn’t twist and pull all three strands snug. They should all line up.

Next, turn the rope over so you can see where the angled lines of the twisted rope begins again and feed the first strand under the first twist, the second under the second twist and the third under the third twist. Pull all three strands snug at the same time, turn the rope over, locate the first twist in the line and repeat until you have all 3” – 4″ braided into the twisted rope.

Next, turn the rope over so you can see where the angled lines of the twisted rope begins again and feed the first strand under the first twist, the second under the second twist and the third under the third twist. Pull all three strands snug at the same time, turn the rope over, locate the first twist in the line and repeat until you have all 3” – 4″ braided into the twisted rope.

You will have some loose ends sticking out and nylon rope can slip back out of the braid, so you now need to take a lighter and burn all these ends until they are melted together into the rope, so they will not slip. Be sure that you burn them so they are smooth and without bumps, or it will be difficult to feed the ends through the D-rings. Do the same with your second snap on the other end of the rope. Now you have your own custom made “Elbow Pull!”

You will have some loose ends sticking out and nylon rope can slip back out of the braid, so you now need to take a lighter and burn all these ends until they are melted together into the rope, so they will not slip. Be sure that you burn them so they are smooth and without bumps, or it will be difficult to feed the ends through the D-rings. Do the same with your second snap on the other end of the rope. Now you have your own custom made “Elbow Pull!”

THE HOURGLASS PATTERN

(Core Strength Leading Training)

Tack up your animal in a surcingle (or lightweight saddle), a snaffle bridle with a drop noseband (and a ring  underneath to attach to the lead rope) and our “Elbow Pull” self-correcting postural restraint. The bridle with the drop nose band will encourage your equine to take proper contact with the bit and not get in the habit of “waving” his tongue over the bit. Adjust it so it is taut enough to keep his head from going so high that he inverts his neck and back, and not so tight that it pulls his head too low. Stand in front of him once you have secured the “Elbow Pull” on the near side and rock his head from the poll to make sure the tension is correct.

underneath to attach to the lead rope) and our “Elbow Pull” self-correcting postural restraint. The bridle with the drop nose band will encourage your equine to take proper contact with the bit and not get in the habit of “waving” his tongue over the bit. Adjust it so it is taut enough to keep his head from going so high that he inverts his neck and back, and not so tight that it pulls his head too low. Stand in front of him once you have secured the “Elbow Pull” on the near side and rock his head from the poll to make sure the tension is correct.

Begin the “Hourglass Pattern” without doing circles at the cones. Lead your animal with the lead rope in your left hand from the left side with your equine’s head at your shoulder when tracking left, and lead your animal with the lead rope in your right hand with your equine’s head at your shoulder when tracking right. Point your left hand (or right hand) in the direction of travel and look where you are going. Say the animal’s name and give the command to “Walk on.” Then look down to see what leg he is leading with and match your steps with his.

Begin the “Hourglass Pattern” without doing circles at the cones. Lead your animal with the lead rope in your left hand from the left side with your equine’s head at your shoulder when tracking left, and lead your animal with the lead rope in your right hand with your equine’s head at your shoulder when tracking right. Point your left hand (or right hand) in the direction of travel and look where you are going. Say the animal’s name and give the command to “Walk on.” Then look down to see what leg he is leading with and match your steps with his.

When you stop, say “And…Whoa” and stop with your feet together. Square him up with both hind legs together and then put both front legs together with equal weight over all four feet and reward from a fanny pack of oats around your waist. Stand quietly until he has finished chewing, change sides (and leading position) after every halt so you are always leading from the “inside” of the arc on which you are traveling, and give the command to “Walk on.” You can add circles at the cones and ground rails once he is consistently walking at your shoulder and prompt with the commands.

You can set up your Hourglass Pattern as pictured above so you can do Leading Training, Obstacle Training, Lunging off and on the Lunge Line, Ground Driving Training and Riding Training without having to move things around. Putting ground rails between the two center cones will encourage your equine to use his hind quarters by stepping well underneath his center of gravity below his torso. This will elevate his front end and produce more action in his joints.

You can set up your Hourglass Pattern as pictured above so you can do Leading Training, Obstacle Training, Lunging off and on the Lunge Line, Ground Driving Training and Riding Training without having to move things around. Putting ground rails between the two center cones will encourage your equine to use his hind quarters by stepping well underneath his center of gravity below his torso. This will elevate his front end and produce more action in his joints.

I work multiple animals, up to four at a time by working one in the arena (with and without the lead rope) with the others tied at the hitch rail just outside the arena by the gate. This enables me to get multiple equines done in a short amount of time and reduces the incidence of animals pacing the fence while others are being worked. Using your facility efficiently can greatly reduce time spent on training.

First he will get proficient on the lead rope in the Hourglass Pattern, and then obstacles will be added at the end of each lesson to facilitate coordination and further increase his postural core strength. During lunging training in good posture, he will be able to sustain equal weight over all four feet and won’t lean from one side to the other. His hind feet will fall into the footprints of the front feet. He will be able to stay in good balance with a consistent rhythm and cadence to all his gaits.

First he will get proficient on the lead rope in the Hourglass Pattern, and then obstacles will be added at the end of each lesson to facilitate coordination and further increase his postural core strength. During lunging training in good posture, he will be able to sustain equal weight over all four feet and won’t lean from one side to the other. His hind feet will fall into the footprints of the front feet. He will be able to stay in good balance with a consistent rhythm and cadence to all his gaits.

Remember, when engaging in the Hourglass Pattern exercises, do not DRILL. You will only need to work your equine first one direction through the pattern with the designated halts between the cones, cross the diagonal and work in the other direction. Once around the pattern each way is enough to do the job. Work your equine a minimum of once a week and a maximum of once every other day. Be sure to leave a day of rest in between for the best results. Your equine will look forward to his time with you, so make the MOST of it!!

Remember, when engaging in the Hourglass Pattern exercises, do not DRILL. You will only need to work your equine first one direction through the pattern with the designated halts between the cones, cross the diagonal and work in the other direction. Once around the pattern each way is enough to do the job. Work your equine a minimum of once a week and a maximum of once every other day. Be sure to leave a day of rest in between for the best results. Your equine will look forward to his time with you, so make the MOST of it!!

To learn more about Meredith Hodges and her comprehensive all-breed equine training program, visit LuckyThreeRanch.com or call 1-800-816-7566. Check out her children’s website at JasperTheMule.com. Also, find Meredith on Facebook, YouTube, Pinterest, Instagram, MeWe and Twitter.

To learn more about Meredith Hodges and her comprehensive all-breed equine training program, visit LuckyThreeRanch.com or call 1-800-816-7566. Check out her children’s website at JasperTheMule.com. Also, find Meredith on Facebook, YouTube, Pinterest, Instagram, MeWe and Twitter.

Covered in TRAINING MULES & DONKEY: A LOGICAL APPROACH TO TRAINING, TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE, EQUUS REVISITED, my TRAINING MULES & DONKEYS DVD SERIES and A GUIDE TO RAISING & SHOWING MULES at www.luckythreeranchstore.com

© 2013, 2016, 2024 Lucky Three Ranch, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

By Meredith Hodges

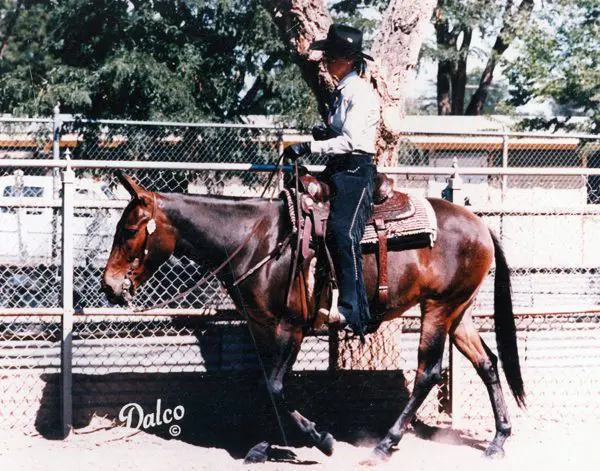

I have done extensive work in training equines for many years and it seems you can never learn enough. If you learn how to ask the right questions, there is always something more to learn just around the corner. It is no secret that things can happen when you push limits and you can get what might seem to be the right results, but then you have to ask yourself…really? You may, for instance get your young Reining prospect to do a spin, but then you should ask yourself if he is executing it correctly so as not to injure the ligaments, tendons and cartilage in his body. If he is not adequately prepared for the spin with exercises that address his core muscle strength and good posture, then he is likely to do the movement incorrectly, putting his body at risk.

Horse trainers have kept us in awe of their unique and significant talents for centuries, and now that their techniques are more public, many equine professionals will pooh-pooh those who attempt a “kinder” approach to training. Scientists who study the equine in motion—its nutrition, biomechanics, care and maintenance—have their own perceptions to offer as to what we can learn about equines. Because many of these studies and tests are done in the laboratory, scientists rarely have the opportunity to follow their subjects throughout a lifetime of activity, as well as having the opportunity to experience what it really means for you as a rider, to be in balance with your equine when you work together, whether you are leading, lunging, riding or driving. If they did, their findings would probably yield quite different results. With all this progressive scientific thought, it seems to me that common sense can often get lost in the shuffle and respect for the living creature’s physical, mental and emotional needs may not be met.

Horse trainers have kept us in awe of their unique and significant talents for centuries, and now that their techniques are more public, many equine professionals will pooh-pooh those who attempt a “kinder” approach to training. Scientists who study the equine in motion—its nutrition, biomechanics, care and maintenance—have their own perceptions to offer as to what we can learn about equines. Because many of these studies and tests are done in the laboratory, scientists rarely have the opportunity to follow their subjects throughout a lifetime of activity, as well as having the opportunity to experience what it really means for you as a rider, to be in balance with your equine when you work together, whether you are leading, lunging, riding or driving. If they did, their findings would probably yield quite different results. With all this progressive scientific thought, it seems to me that common sense can often get lost in the shuffle and respect for the living creature’s physical, mental and emotional needs may not be met.

It is true that bribery never really works with an equine, and many people who attempt the “kind” approach do get caught up with bribery because they are unskilled at identifying good behaviors and waiting to reward until the task is performed. However, reinforcement of positive behaviors with a food reward does work if you can figure out how to adhere to the program, and be clear and consistent in how you behave and what you expect. In order to do this, you need to really pay attention to the whole equine, have a definite exercise program that has been proven to work in developing the equine’s good posture and strength, and be willing to work on yourself as well as your equine. A good program for your equine will require that you actively participate in the exercises as well. That way, you will also benefit while you are training your equine.

People feel better when they pay attention to their diet and are aware of their posture while practicing physical activities—and, in the same respect, an equine will perform willingly and happily if he feels good. Horses have as many different postures as do people, and there are generalized postures that you can easily notice and predict in specific breeds of horses. For instance, the American Saddlebred has a higher body carriage than that of the Quarter Horse. However, each individual within any breed is not naturally born in good posture and might need some help to get in good posture in order to exercise correctly.

There are varying levels of abuse and most abuse happens out of ignorance. Many training techniques appear to get the equine to do what you want, but the question then becomes, “How is he doing this and will it result in a good strong body or is it in opposition to what would be his best posture and condition?” Any time you take the equine out of good posture to accomplish certain maneuvers, you are abusing his body, and this can result, over time, in  degenerative breakdown. For instance, those who get in a hurry in Dressage and do not take a full year at each level in order to develop their equine’s body slowly and methodically may discover, several years later, that their animal has developed ringbone, side bones, arthritis or some other internal malady. These types of injuries and malformations are often not outwardly exhibited until it is too late to do anything about them.

degenerative breakdown. For instance, those who get in a hurry in Dressage and do not take a full year at each level in order to develop their equine’s body slowly and methodically may discover, several years later, that their animal has developed ringbone, side bones, arthritis or some other internal malady. These types of injuries and malformations are often not outwardly exhibited until it is too late to do anything about them.

In my experience with my draft mule rescues, Rock and Roll, this became blatantly apparent to me. When Rock had to be euthanized in December of 2011, a necropsy was performed after his death. When the necropsy report came back and we were able to ascertain the long-term results of his years of abuse, neglect and bad posture, we found it a wonder that he was able to get up and down at all, much less rear up and play with Roll and trot over ground rails in balance.

His acetabulum (or hip socket) had multiple fractures. The upper left photo shows Rock’s normal acetabulum and the upper right photo shows Rock’s fractured acetabulum. The photo at right shows the head of each of Rock’s femurs. Rock’s left femoral head was normal, while the right, injured femoral head was virtually detached from the hip socket and contained fluid-filled cysts. There was virtually no cartilage left on the right femoral head, nor on the right acetabulum. It was the very fact that my team and I made sure that Rock was in balance and took things slowly and in a natural sequence that he was able to accomplish what he did and gain himself an extra year of quality life.

Tragically, many equines are suffering from abuse every day, while they are trying to please their owners and do what is asked of them. Their owners and trainers take shortcuts that compromise the equine’s health. It could be that these owners and trainers are trying to make choices with limited knowledge and really don’t know whom to believe. But ignorance is not a valid defense and sadly, the animal is the one that ends up suffering.