From the SWISS BULLETIN: The Mule as a Workhorse in Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages

By Elke Stadler

The history of mankind is closely connected with the use of the working force of animals. Animal power was of special importance in transport and traffic – before motorization it was the only available movable driving force, almost at any time and versatile. What people themselves could not wear or pull; oxen, mules, horses and donkeys carried or pulled. In the past, despite their essential importance for working life and the economy, the working animals were hardly noticed in literature.

The work of the animals was so natural to the people of that time that it was not considered necessary to describe their characteristics or the circumstances of their use for people in more detail. Thus, in historical scriptures, animals appear even rarer than slaves and farmhands; they stand at the end of the hierarchy of values and remain mutely. But there is much to be learned from the late antique veterinary writings about their living conditions. The “Mulomedicina Chironis” – the most significant surviving ancient scripture about medical treatment of equids – was used until the Middle Ages and, as copies prove, further into the late Gothic period.

Cattle and Horse

At that time, cattle were the most important draft animals, less for meat production, and milk was also of little importance. Cattle were mainly used in agricultural traction work or heavy transports with wagons. Oxen were indispensable for long-distance transport. No person, no matter how much they preferred mules, camels or even elephants, could do without cattle. They were much less demanding of food and care than the sensitive horse, which was expensive to keep. The mule took a special position because of its outstanding qualities. Horses are hardly mentioned in the old writings as draft animals for heavier loads. Mostly, they were used for light wagons. Horses were the mount of the high-ranking men, both civilian and military, and also served as a pack animal.

At that time, cattle were the most important draft animals, less for meat production, and milk was also of little importance. Cattle were mainly used in agricultural traction work or heavy transports with wagons. Oxen were indispensable for long-distance transport. No person, no matter how much they preferred mules, camels or even elephants, could do without cattle. They were much less demanding of food and care than the sensitive horse, which was expensive to keep. The mule took a special position because of its outstanding qualities. Horses are hardly mentioned in the old writings as draft animals for heavier loads. Mostly, they were used for light wagons. Horses were the mount of the high-ranking men, both civilian and military, and also served as a pack animal.

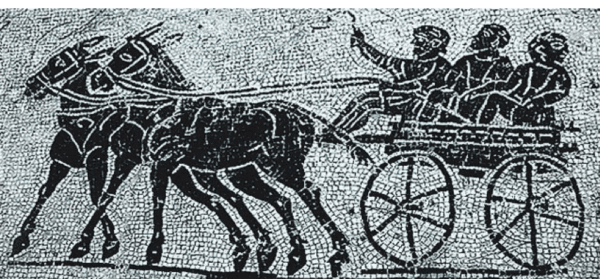

The most important limitation of the horse’s work in the draft service was technical difficulties. The shoulders of the horse protrude only very little, thus, the use of a shoulder yoke becomes impossible; the animal must pull with a neck harness, or a yoke sitting very high at the neck. In this way, the draft-horses and mules are represented also on Roman reliefs. Larger loads were not possible since they strangled the breathing of the animal with this tension. So, the animal could only use a small part of its body weight for pulling. The collar was unknown in Antiquity and late Antiquity, it was used for the first time in the Middle Ages.

Mule Breeding

In ancient times the mule played a special role in transport and traffic. On the road, it is the most popular draft animal due to its optimal characteristics. Although it is weaker than an ox, it is much faster than the ox. At the same time, a mule requires less food and care than a horse. It is also easier to use because of its general calmness. Thus, mule breeding yielded more profit than the usual breeding of medium-value horses. Their value was even compared to that of noble racehorses.

High quality mares were used for breeding at the age of four to ten years, and donkey stallions between three and ten years. We can read that the Arcadian or Reatic donkey stallions should be preferably black or spotted, but not of grey color. Onagers, Asian wild donkeys, were also used for mating. Particularly appreciated were donkey stallions descended from a donkey that had been mated by an Onager. The wild nature was then broken and the begotten animal possessed the tameness of the mother as well as the dexterity of the Onager. The one-year old foal was separated from its mother and kept on rocky, mountainous terrain, so that it got hard hooves as a condition for profitable use in transport.

Use of Female and Male Mules

Female animals were used primarily for pulling wagons because of their agility, while male mules were used to carry loads. Various documents show this division for different purposes. Emperor Serverus Alexander gave his provincial leaders six female mules, two male mules and two horses. It is obvious that the female mules were intended for specific use as draft animals, the male mules as pack animals and the horses for mounts. The female mules were reserved for pulling which is evident from the fact that they were normally traded as a team. If one had a flaw, the seller had to take back both animals. It was especially popular when all the animals in front of a cart had the same color. The veterinarians gave recipes for dyeing the hair of the draft animals when it was not appropriate. To make white hair black, three ‘scripula’ (Roman unit of weight) cobbler’s blacks, four ‘scripula’ oleander’s juice and some goat fat are mixed, crushed and then applied. To make black hair white, a pound of wild cucumber root and twelve ‘scripula’ soda are crushed into powder, a cup of honey added, and then applied.

Female animals were used primarily for pulling wagons because of their agility, while male mules were used to carry loads. Various documents show this division for different purposes. Emperor Serverus Alexander gave his provincial leaders six female mules, two male mules and two horses. It is obvious that the female mules were intended for specific use as draft animals, the male mules as pack animals and the horses for mounts. The female mules were reserved for pulling which is evident from the fact that they were normally traded as a team. If one had a flaw, the seller had to take back both animals. It was especially popular when all the animals in front of a cart had the same color. The veterinarians gave recipes for dyeing the hair of the draft animals when it was not appropriate. To make white hair black, three ‘scripula’ (Roman unit of weight) cobbler’s blacks, four ‘scripula’ oleander’s juice and some goat fat are mixed, crushed and then applied. To make black hair white, a pound of wild cucumber root and twelve ‘scripula’ soda are crushed into powder, a cup of honey added, and then applied.

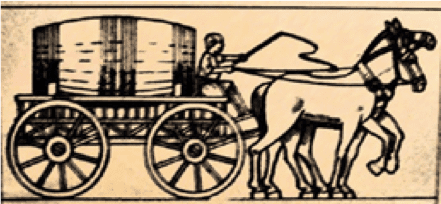

Most mules were not used as valuable draft animals in private passenger transport, but in public transport by rental car companies or by cargo. The provisions of Codex Theodosianus (late antiquity collection of laws) the ‘cursus publicus’, can give an approximate impression. Two car types are mentioned, the four-wheeled ‘raeda’ and the two-wheeled ‘birota’. The ‘raeda’ was fitted with eight mules in summer and ten in winter, 1000 pounds could be carried. When used by people, this corresponded to seven to eight passengers. For the ‘birota’ on the other hand, three mules and a maximum load of 200 pounds were prescribed, for a person’s use, this was two passengers.

Most mules were not used as valuable draft animals in private passenger transport, but in public transport by rental car companies or by cargo. The provisions of Codex Theodosianus (late antiquity collection of laws) the ‘cursus publicus’, can give an approximate impression. Two car types are mentioned, the four-wheeled ‘raeda’ and the two-wheeled ‘birota’. The ‘raeda’ was fitted with eight mules in summer and ten in winter, 1000 pounds could be carried. When used by people, this corresponded to seven to eight passengers. For the ‘birota’ on the other hand, three mules and a maximum load of 200 pounds were prescribed, for a person’s use, this was two passengers.

Adventure by Road

The journey with such public transport was accompanied by wild screams, whip cracks from a drunken coachman and clouds of dust, reports a letter writer named Eustathios: A trip with mules that were boisterous by doing nothing and feeding too much he avoided – and prefered to walk.

The journey with such public transport was accompanied by wild screams, whip cracks from a drunken coachman and clouds of dust, reports a letter writer named Eustathios: A trip with mules that were boisterous by doing nothing and feeding too much he avoided – and prefered to walk.

Cross-country journeys were quite risky, as Roman poet Vergil describes, especially because of the daring overtaking maneuvers of competing truck owners. But sometimes a driver had to go under the yoke himself when a mule had got stuck in the mud of the soaked and crushed road. During overtaking maneuvers on the narrow country roads there was damage to the gravestones on the roadside, as an inscription proves. This also shows that mules were used in long-distance traffic to Gaul. Emperor Julian tells about the dangers on narrow Alpine roads, to which both passengers and draft animals were exposed, so does a rock inscription for remembering a road construction from the year 373 A.D.

In the Jungle of Cities

In the mostly narrow cities, the mule-drawn heavy wagon traffic caused great difficulties. Since the early imperial period, carriage traffic and riding in the city during the first ten hours after sunrise were therefore forbidden. Trips in connection with construction measures were permitted, and these were already enough to endanger the lives of pedestrians on the roads with their big wagons and high stacked loads.

A case story, described by a lawyer, shows what could have happened. Two mule-drawn ‘plaustra’ (load carts) drive up the Capitol slope in Rome. The mule leaders of the first one are pressing against the ‘plaustrum’ so that the mules could pull easier. However, the first carriage begins to roll back anyway, and the mule drivers jump out between the carriages. The first team then rolls onto the second, which now also rolls down backwards and crushes into a boy. The lawyer blames the leader of the first carriage for this accident, as he would be responsible for the overloading of the first carriage. Such incidents were as other sources show not uncommon.

Medical Care

This hard use of mules in driving is reflected in the treatment instructions of late antique veterinarians. The neck injuries caused by the yoke, which Pelagonius expressly refers only to mules, are of special importance. It was recommended that in order to prevent neck injuries of mules or to heal after damage has occurred, was to use an ointment made from fresh pig fat boiled with vinegar. For injuries of the neck and back of the mules, a remedy made of boiled wax, hot resin, verdigris and oil is used. Another remedy for neck treatment is described in this way; rotting chips from the middle of a fig tree are to be dried and burned to ashes in a clean place. This is sieved and then mixed in a mortar with wine, old oil and the protein of two eggs. To make the neck supple – this is the prerequisite for clamping it in the yoke – the neck is thoroughly washed with soap and then rubbed with a carefully beaten mixture of rainwater and protein. Mules were considered less valuable than horses or assessed to be more tolerant of injuries – such as an injury that is indicated by a crossed gait and an insecure step, where the animal trips over stones and a contracted hip.

A horse should be treated carefully and immediately to prevent major damage. However, if the suffering animal is a mule, it should first be stretched tighter in the yoke, so that sweat and pain will smash all pain. After work, it should be treated with the following remedy; twenty laurels are finely crushed with soda and heated with a handful of green rue, vinegar and laurel oil. Then they rubbed this on the center of the head between the ears, they also took a remedy-soaked piece of wool and laid it on this area. Another agent is made from barley flour and resin. These treatments are accompanied by the application of a general strengthening agent made from crushed crayfish, goat’s milk and oil.

Pack Mules

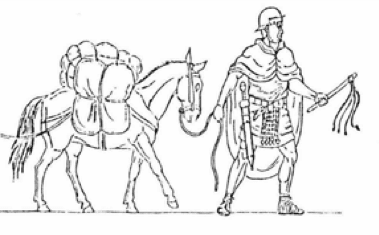

Male mules were used to carry less extensive loads in cities and agriculture because of their greater strength. The typical work was the transport of pole wood for plantations. Traders kept their mules directly in their shops. There is a case described in the Digests (scripts of ancient legal scholars) where a horse was led into a shop and was sniffing at the mule there. It kicked and broke the back of the horse’s leader. In the troop, each centurion had one such pack mule, which had to carry the heavier parts of the equipment on the marches.

Male mules were used to carry less extensive loads in cities and agriculture because of their greater strength. The typical work was the transport of pole wood for plantations. Traders kept their mules directly in their shops. There is a case described in the Digests (scripts of ancient legal scholars) where a horse was led into a shop and was sniffing at the mule there. It kicked and broke the back of the horse’s leader. In the troop, each centurion had one such pack mule, which had to carry the heavier parts of the equipment on the marches.

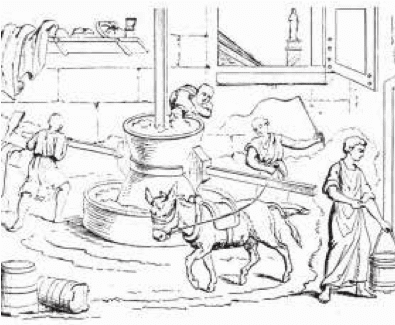

Drudgery in the mills

Mules were often used, as donkeys and horses were, to drive mills when they were no longer usable for other services. They were harnessed with a hard grass rope in front of the mill beam, the head was usually masked. They trotted in a furrow, always pushed by blows in the circle around. The bad condition of the animals corresponded to the gruelling work. In the “Methamorphoses”, Apuleius describes that the necks were swollen of wound rot, the nostrils were flaccid and dilated from coughing and dusty air. The body was disfigured by the constant blows and mange, the feet clumped by traveling permanently in a circle. These sufferings are also reflected in the veterinary writings, but the mill animals were certainly no longer treated.

Mules were often used, as donkeys and horses were, to drive mills when they were no longer usable for other services. They were harnessed with a hard grass rope in front of the mill beam, the head was usually masked. They trotted in a furrow, always pushed by blows in the circle around. The bad condition of the animals corresponded to the gruelling work. In the “Methamorphoses”, Apuleius describes that the necks were swollen of wound rot, the nostrils were flaccid and dilated from coughing and dusty air. The body was disfigured by the constant blows and mange, the feet clumped by traveling permanently in a circle. These sufferings are also reflected in the veterinary writings, but the mill animals were certainly no longer treated.

Mounts

The mule was used rarely for riding in Antiquity, it was the simpler mount. Horace (poet) illustrates a simple but also free life in this way: He could bridle a mule at any time and head all the way to Taranto, even if the loins of the animal were rubbed sore by the heavy coat bag and the sides by the weight of the rider. The veterinarians list these specific injuries caused by riding, as well as, by loads being too heavy. The wounds are treated with ointments mixed from salt, wine, oil, raisin wine, pork fat and onions. In more severe cases, blood is taken from the veins of the groin area and mixed with salt, pork fat and oil. This is applied, and if necessary, plastered with ointment. For wounded skin caused by pressures, a dough-like mixture made of fine wheat flour, incense dust, egg yolk and vinegar is applied to the sore spots.

The mule was used rarely for riding in Antiquity, it was the simpler mount. Horace (poet) illustrates a simple but also free life in this way: He could bridle a mule at any time and head all the way to Taranto, even if the loins of the animal were rubbed sore by the heavy coat bag and the sides by the weight of the rider. The veterinarians list these specific injuries caused by riding, as well as, by loads being too heavy. The wounds are treated with ointments mixed from salt, wine, oil, raisin wine, pork fat and onions. In more severe cases, blood is taken from the veins of the groin area and mixed with salt, pork fat and oil. This is applied, and if necessary, plastered with ointment. For wounded skin caused by pressures, a dough-like mixture made of fine wheat flour, incense dust, egg yolk and vinegar is applied to the sore spots.

A special feature in those times were dwarf mules, called ‘mulae pumilae’, a curious luxury object of which the roman poet Martialis ironically states, that one often sits higher on the floor.

In the Middle Ages

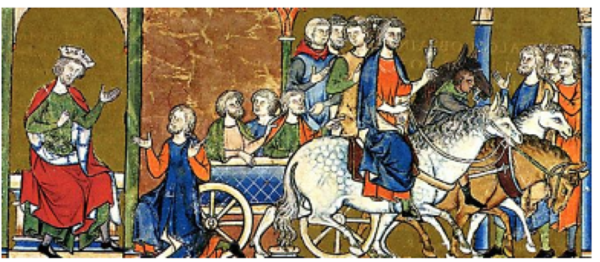

Although mules were regarded by the church leaders as originating from an unnatural connection, and thus had a bad reputation, the mule nevertheless experienced a great appreciation in the early Middle Ages. Since Spanish mules are a noble gift, Emperor Charlemagne sent them to Caliph Harun Rashid. Mules and their Saracen guardians were bestowed by Robert Guiscard (Norman leader) to the Abbot of Montecassino. The mule is often mentioned as a mount of clergy. Gallus, for example, uses a mule for his journey to the Swabian ducal court. Also, for the journey of Goar (Priest, later holy spoken) to the royal court, a mule or a donkey is intended. Bishop Gregory of Tours, mentions mules among the farm animals of the monastery St. Martin, which were obviously riding animals. Because of the clergy’s preference for mules, the devil – as Notker (poet and scholar) tells us he turns into a mule to tempt the bishop to buy him, seduces him and kills him on the way out. A degree accordingly acts against the excessive dealing of clergy with mules. Of course, mules were often used as pack animals in the early Middle Ages, just like horses. Already Isidor from Sevilla (Archbishop) speaks about the ‘mulus sagmaria’ (Latin: pack mule) beside the ‘caballus sagmarius’ (packhorse). Some of the mules and horses with which the Irish bishop Marcus returned from his trip to Rome must have been pack animals as books, gold objects and robes are mentioned as transported goods. In the Vita Hludovici (anonymous biography of Louis the Pious) mules are also mentioned beside horses, working a mission as they transported ship parts through the woods. Mules are also considered a pack animal in custom regulations.

Although mules were regarded by the church leaders as originating from an unnatural connection, and thus had a bad reputation, the mule nevertheless experienced a great appreciation in the early Middle Ages. Since Spanish mules are a noble gift, Emperor Charlemagne sent them to Caliph Harun Rashid. Mules and their Saracen guardians were bestowed by Robert Guiscard (Norman leader) to the Abbot of Montecassino. The mule is often mentioned as a mount of clergy. Gallus, for example, uses a mule for his journey to the Swabian ducal court. Also, for the journey of Goar (Priest, later holy spoken) to the royal court, a mule or a donkey is intended. Bishop Gregory of Tours, mentions mules among the farm animals of the monastery St. Martin, which were obviously riding animals. Because of the clergy’s preference for mules, the devil – as Notker (poet and scholar) tells us he turns into a mule to tempt the bishop to buy him, seduces him and kills him on the way out. A degree accordingly acts against the excessive dealing of clergy with mules. Of course, mules were often used as pack animals in the early Middle Ages, just like horses. Already Isidor from Sevilla (Archbishop) speaks about the ‘mulus sagmaria’ (Latin: pack mule) beside the ‘caballus sagmarius’ (packhorse). Some of the mules and horses with which the Irish bishop Marcus returned from his trip to Rome must have been pack animals as books, gold objects and robes are mentioned as transported goods. In the Vita Hludovici (anonymous biography of Louis the Pious) mules are also mentioned beside horses, working a mission as they transported ship parts through the woods. Mules are also considered a pack animal in custom regulations.

The existence of humans and the development of all processes, political and social, were marked by the importance of the working animals, not only in Antiquity and the Middle Ages, but also far into modern times. In the beginning it was mainly cattle that carried the workload. Over time there were shifts, the cattle were substantially relieved first in later Antiquity by the mule. Finally, in the Middle Ages the horse, caused by changes in animal technology – horseshoe fittings and collar – became more universally applicable. However, the donkey’s services remained to limited use.

Excerpt from: “Animal laborans – Das Arbeitstier und sein Gebrauch im Transport und Verkehr in der späten Antike und im Mittelalter” (The work animals and its use in transport and traffic of late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages) in: L’uomo di fronte al mondo animale nell’ alto medioevo; Settimane di studio del centro italiano di studi sull’alto medievo XXXI, 1983, 2 vol., Spoleto 1985; vol.1, p.457-578 (essay monograph)

Picture references:

- Mule whith neck joke – http://wwwg.uni-klu.ac.at/archeo/alltag/10vieh.htm

- Carpentum, carriege for journey – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maria_Saal_Dom_Grabbaurelief_Reisewagen_in_die_Unterwelt

- Plaustrum, wagon for load – https://www.artisanat.ch/reportages/578-histoire-des-voies-de-communication-et-moyens-de-transport-1ere-partie.html

- http://www.forumtraiani.de/lebhafte-roemische-strassen/

- Cisium, light carriage – http://www.ostia-antica.org/regio2/2/2-3.htm

- Roman soldier with mule – https://www.exfabrica-miniatura.de/Auxiliar-Infanterist-mit-Maultier

- Grain mill in Pompeji, ca. 200 v. Chr – http://www.voegeles-muehle.de/geschichte

- Mule, mounts in the Middle Ages – http://www.brandenburg1260.de/pferd-im-ma.htm

- Playing card 1440-1445 – https://www.pinterest.de/pin/94646029645701226/?lp=true

- Snippet: Absalon leaves David to plan a conspiracy, Maciejowski-Bible, 13. Century – http://www.stupor-mundi.info/2016/08/22/reisen-im-mittelalter/